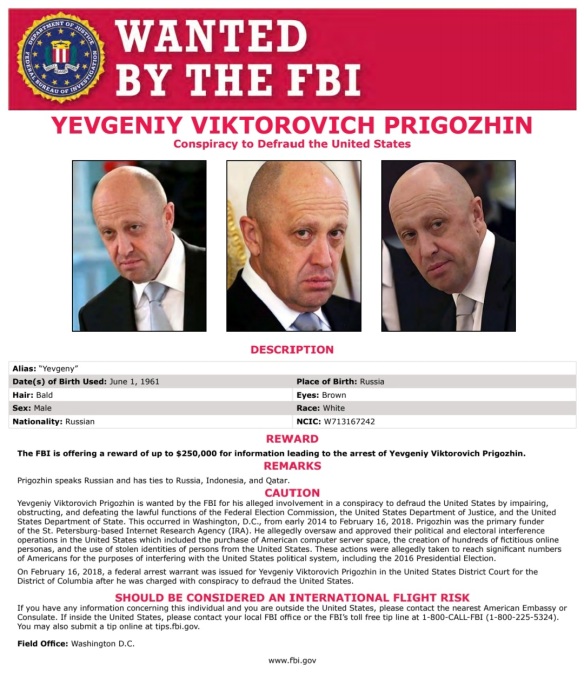

Yevgeny Prigozhin (above). On August 23, 2023, the owner of ChVK Vagnera, popularly known as Gruppa Vagnera (the Wagner Group), Yevgeny Prigozhin and nine other passengers were killed in a jet crash north of Moscow. The crash came only two months after the Wagner Group Rebellion in the Russian Federation. For those unfamiliar with that episode, on June 23, 2023, Prigozhin drove elements of his military organization into the Russian Federation from Ukraine with the purpose of removing by force the Russian Federation Defense Minister Russian Army General Sergei Shoigu and ostensibly Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation), Russian Army General Valery Gerasimov, from their posts. A deal brokered by Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko was struck that caused the Wagner Group to halt. The Wagner Group, a private military corporation, had fought alongside the Russian Federation Armed Forces. Since the first day of its special military operation in Ukraine. Prigozhin, became greatly frustrated over the delinquencies, deficiencies, and ineptitude of the Russian Federation military leadership which his organization has been directed to work under. If not the evidence itself, the manner in which the air disaster transpired, and a history of reported behavior by Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin, led many see logic behind the common wisdom that he was involved. Yet, it was certainly not enough to prove he ordered albeit a not-so-unique form of execution. As of the time of this writing, many major events have occurred since the Prigozhin’s jet crash. Yet, there seems something more unique about the Prigozhin jet crash story. There remains be much to understand regarding Prigozhin’s denouement and the closing of another tragic chapter of Putin’s life. Examining the facts of this episode, greatcharlie has sought to provide a better picture in particular of the interplay of light and dark forces that guide Putin’s behavior.

This essay should be considered a continuation of the preceding greatcharlie post.

On August 23, 2023, a private Embraer jet flying to St. Petersburg crashed north of Moscow killing all 10 passengers onboard. Onboard was the owner of ChVK Vagnera, popularly known as Gruppa Vagnera (the Wagner Group), Yevgeny Prigozhin, two other top Wagner Group officials, to include Dmitry Utkin, Prigozhin’s four bodyguards and a crew of three. The crash garnered international attention as it came only two months after the Wagner Group Rebellion in the Russian Federation. For those unfamiliar with that episode, on June 23, 2023, Prigozhin drove elements of his military organization into the Russian Federation from Ukraine with the purpose of removing by force the Ministr Oborony Rossijskoj Federacii (Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation hereinafter referred to as the Russian Federation Defense Minister) Russian Army General Sergei Shoigu and ostensibly Chief of General’nyy shtab Vooruzhonnykh sil Rossiyskoy Federatsii (General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation), Russian Army General Valery Gerasimov, from their posts. Prigozhin’s Wagner Group troops advanced to just 120 miles (200 kilometers) from Moscow. However, a deal brokered by Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko was struck that caused the Wagner Group to halt. Prigozhin withdrew his forces to avoid what all sides feared would be the further “shedding Russian blood.” The Wagner Group, a private military corporation, had fought alongside the Russian Federation Armed Forces since the first day of its special military operation in Ukraine. Prigozhin, became greatly frustrated over the delinquencies, deficiencies, and ineptitude of the Russian Federation military leadership which his organization has been directed to work under. By 2023, Prigozhin unquestionably behaved as if he were frenzied, and perhaps justifiably and reasonably so, with the great injustice put upon Wagner Group troops in Ukraine as well as the troops of the Russian Federation Armed Forces during the Spetsial’noy Voyennoy Operatsii (Special Military Operation). On June 23, 2023, however, Prigohzin shifted from simply accusing Shoigu and Gerasimov of poorly conducting by then a 16-month-long special military operation when events took a graver turn. Prigozhin accused forces under the direction of Shoigu and Gerasimov of attacking Wagner Group camps in Ukraine with rockets, helicopter gunships and artillery and as he stated killing “a huge number of our comrades.” The Russian Federation Defense Ministry denied attacking the camps. Prigozhin then set off with elements of the Wagner Group to attack the Defense Minister in Moscow.

Assuredly, if Prigozhin’s deadly jet crash was not accidental and ordered by the highest authorities in the Russian Federation government, the decision was most likely multifactorial. Many opinions have offered by analysts and experts on the Russian Federation on how Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin benefitted from the action were also offered. If not the evidence itself, the manner in which the air disaster transpired, and a history of reported behavior by Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin, led many see logic behind the common wisdom that he was involved. Yet, it is certainly not enough to prove he ordered such a not-so-unique form of execution in authoririan regimes, also occasionally witnessed in democracies. Omnia mors poscit. Lex est, non pœna, perire. (Death claims all things. It is law, not punishment, to die.)

The media cycle on the untimely death of Prigozhin and senior commanders of his Wagner Group appeared to reach it apogee by the start of September 2023. However, Putin seemingly sought to pry the door to it open. For reasons that are not completely clear, and a timing not easily understood,by greatcharlie, on October 5, 2023, Putin suggested that the investigation of Russian Federation’s investigative Committee was not barren, and its head reported to him that evidence was found indicating that the jet crash which killed Prigozhin was caused by hand grenades detonating inside the aircraft, not by a missile attack. Although frugal with information immediately following the air disaster and days that followed, the extraordinary and surprising revelations by Putin of additional information garnered during the investigation was provided in a very public setting. Similarly surprising was the fact that Putin also went as far as to make disparaging suggestions about the use of narcotics among passengers on his jet, ignoring Prigozhin’s family’s pain and disregarding the couteousy of displaying respect for the dead. For those interested observers interested in Prigozhin’s demise, the way in which it occurred provided a proper mystery.

As of the time of this writing, many major events have occurred since the Prigozhin’s jet crash. The 2023 North Korea–Russia summit between Putin and Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Chairman Kim Jung-un was held in Moscow on September 23, 2023. Putin in his first foreign visit after the International Criminal Court in The Hague issued a warrant for his arrest visited Kyrgyzstan on October 12, 2023. Putin then visited People’s Republic of China President Xi Jinping in Bejing on October 17, 2023. Each event provided ample opportunity to further assess Putin’s words and behavior to construct a firmer understanding of the man and his decisionmaking. Yet, there seems something more unique about the Prigozhin jet crash story. After all, Putin and Prigozhin, at least for a time, were true friends. That was somewhat evident in Putin’s initial public comments on the crash. In many respects, for Putin, the deadly episode amounted to a private tragedy within what seemed a public conflict. Many details will likely remain kept from both the public and the newsmedia. Still, from what has been been presented to the public, there remains be much to gain regarding Prigozhin’s denouement and the closing of another tragic chapter of Putin’s presidency. Examining the facts of this episode, greatcharlie has sought to provide a better picture in particular of the interplay of light and dark forces that guide Putin’s behavior.

Unless there is additional information so newsworthy concerning Prigozhin that it cannot be dismised or avoided, greatcharlie believes this will be it last entry on the passed-on Wagner Group owner. Still, as has been the case with its previous posts, greatcharlie hopes this essay will stimulate among readers, particularly students, new lines of thought, even kernels of ideas on how US foreign and national security policy analysts and decisionmakers, as well as analysts and decisionmakers of other governments might proceed concerning the Russian Federation. Certainly, it would be humbled to see it take its place among ideas being exchanged internationally on Ukraine and Putin through which it may eventually become part of the greater policy debate. Though, for greatcharlie, it would be satisfying enough to have this commentary simply stand alone as one of its many posts on foreign and national security policy. Stat sua cuique dies; breve et irreparabile tempus omnibus est vitæ; sed famam extendere factis, hoc virtutis opus. (Each one has his appointed day; short and irreparable is the brief life of all; but to extend our fame by our deeds, this is the work of virtue.

Putin in a pensive mood (above). Part 1 of this essay, the discussion revolved around the dynamics of Prigozhin’s personal and professional relationships with Putin. When Putin met Prigozhin, he was already a relatively successful businessman, energized by connects created by a school chum Boris Spektor. After Putin became the Russian Federation President, he presented Prigozhin with lucrative business opportunities, chances of a lifetime. Prigozhin broke with those initial business partners and struck on his own, working primary via Concord Management and Consulting services. From a successful businessman, Prigozhin moved into realm of the country’s oligarchs. That was a circumstance not too unusual in Putin’s Russia. Between Putin and loyal associates, unique professional opportunities were developed on the basis of the quality of their personal relationships with him. Breaks between Putin and associates would more often be the result of personal differences that cropped up, unpredicted and unacceptable. Often those former associates completely vanished, quietly from the scene in the Russian Federation. There are those in the West who would insist that Putin nothing more than a black hearted snake, unable to have lasting, enjoyable relationships with associates. Equally, they would likely proffer that all of his relationships have been based on their utility for him. In that vein, there had to be some advantage gained or there would be no reason to know someone. The relationship between Putin and Prigozhin, when it began, was hardly based on utility.

Putin’s Personal Relationships Versus Professional Relationships: Some Nuance

In Part 1 of this essay, the discussion revolved around the dynamics of Prigozhin’s personal and professional relationships with Putin. An acute example of individuals in the Russian Federation with solely professional relationships with Putin are the oligarchs. Oligarchs managed over the years to amass great wealth and great power and influence within the country to the extent possible under the oversight and control of Putin. Their support of regime and its policies is explicit. A number of those who have failed to meet Putin’s expectations, even to the extent of ostensibly posing a political threat to his regime, have found themselves arrested on charges such as fraud, tax evasion, misappropriation of funds, and embezzlement. Trials of such individuals have been very public. Putin’s professional relationships with the oligarchs may be useful and at times convenient, but hardly friendly. PUtin’s relationship with Prigozhin was personal. When Putin met Prigozhin, he was already a relatively successful businessman, energized by connects created by a school chum Boris Spektor. After Putin became the Russian Federation President, he presented Prigozhin with lucrative business opportunities, chances of a lifetime. Prigozhin broke with those initial business partners and struck on his own, working primary via Concord Management and Consulting services. From a successful businessman, Prigozhin moved into realm of the country oligarchs. That was a circumstance not too unusual in Putin’s Russia. Between Putin and loyal associates, unique professional opportunities were developed on the basis of the quality of their personal relationships with him. Breaks between Putin and associates would more often be the result of personal differences that cropped up, unpredicted and unacceptable. Often those former associates completely vanished, quietly from the public scene in the Russian Federation.

There are those in the West who would insist that Putin nothing more than a black hearted snake, unable to have lasting, enjoyable relationships with associates. Equally, they would likely proffer that all of his relationships have been based on their utility for him. In that vein, there had to be some advantage gained or there would be no reason to know someone. The idea is essentially slander. The relationship between Putin and Prigozhin, when it began, was hardly based on utility. By the accounts from the majority of observers to include the independent newsmedia and independent research groups as well as the opposition political parties in the Russian Federation, their friendship grew from initial social contacts tied to Putin’s visits to Prigozhin’s restaurants.

Many long-term personal relationships that have also had professional links to Putin tended to be low profile and given relatively scant newsmedia coverage in the country. Some Russian Federation analysts and experts might point out is Putin’s long-term relationship with Sergei Roldugin.

Sergei Roldugin has been friends with Putin since the late 1970s Since In those days, Roldugin has affectionately referred to Putin with the diminutive “Volodya”, and still does so today. Putin met Roldugin via his older brother, Yevgeny, who attended the KGB training with Putin. Allegedly it was Roldugin who introduced Putin to his wife Lyudmila. Putin chose Roldugin as the godfather of his first daughter, Maria, born in 1985. Roldugin is known to be a celebrated cellist based in St Petersburg, but he has also been labeled a businessman. The label has some meaning to the extent that Roldugin is a key figure in the covert efforts “to hide Putin’s fortune.”

Due to his low-key presence, some believe Roldugin has actiually been excused from serving Putin in some way financially. However, investigative journalists in the Russian Federation estimate that nearly $2 billion have moved through accounts in his name. With direct concern to the music arts, Roldugin was allowed to open and operate a “Musical House” in an opulent 19th-century palace in St. Petersburg which was not a mean financial feat.

There is also Putìn’s ex-wife, Lyudmila Putina, now remarried and named Lyudmila Ocheretnaya (hereinafter referred to as Lyudmila). Putin married Lyudmila on July 28, 1983. At the time, she was a flight attendant for the Kaliningrad branch of Aeroflot. The couple had two daughters, Maria, aforementioned, born in Leningrad on April 28, 1985 in Leningrad, and Katerina born on August 31, 1986 in Dresden, East Germany. After 30 years of marriage, Putin and wife publicly announced their divorce publicly before the Russian Federation newsmedia at the State Kremlin Palace during the intermission of a performance by the Kremlin Ballet.

In January 2016, Lyudmila was remarried to Artur Ocheretny. Reportedly Ocheretny, health and fitness expert, owns luxury real estate in Europe. Presumably with blessing of her ex-husband and his support Lyudmila has generated millions through the Centre for the Development of Inter-personal Communications (CDIC) which she created and supports. CDIC’s offices are located in the center of Moscow, on Vozdvizhenka Street in the building previously known as Volkonsky House. Rents in the building wich amount to about $3–4 million are paid to the company Meridian, which is in turn owned by a company known as Intererservis. Intererservis is wholly owned by Lyudmila. The chairman of CDIC’s management board is Lyudmila’s second husband Ocheretny.

As with Prigozhin, there were business transactions and opportunities earn income involved in the relationships between both Sergei Roldugin and Lyudmila Ocheretnaya that only the Russian Federation President could create. To that extent, the difference between a personal and a professional relationship with Putin might appear nonexistent for many observers. However, it does exist. When Putin makes the choice to ask a favor, a special task, of a friend, he imaginably makes the assessment that he can expect a degree of trust and dependability of that individual. For the friend entreated to assist the Russian Federation President, nothing more would expected than to follow Putin’s instructions to the letter. Any rewards, meager or of great magnitude would be for Putin to decide. Suffice to say the offer of “assistance” from Putin would require close friends to walk out on thin ice. The last thing the wise amount them would want to do is disappoint Putin even by happenstance. In particular, one would not want to act on any wherewithal provided from Putin’s largess behind the Russian Federation President’s back, so to speak The consequences would certainly been severe. Their involvement with his enterprises is something to fear. Whether a friend of Putin can, through their own actions, expiate for his or her betrayal of Putin’s trust is unknown to greatcharlie. Perhaps that has hardly been the case. Prigozhin may have been the rare exception on couple of occasions, likely over matters unrelated to the Wagner Group. However, that can only be supposed in the abstract. One might consider the apposite Act V, scene 4 of William Shakespeare’s play The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1589-1593) in which Valentine discovers his best friend Proteus attempted, unsuccessfully, to curry the affections of his beloved, Sylvia. In response to the outrageous act by Proteus, the much wounded Valentine states: “I am sorry I must never trust thee more, / But count the world a stranger for thy sake. / The private wound is deepest: O time most accurst, / ‘Mongst all foes that a friend should be the worst!.” Remarkably, despite what was said, the two men reconcile at the end of the play after Proteus repents and Valentine forgives him. However, Putin once betrayed has hardly been forgiving.

Prigozhin failed to meet Putin’s expectations with regard to the Wagner Group and possibly Concord. Prigozhin did not object or seem to worry about accepting opportunities he surely had never foreseen or handled before. Not so quietly, he amassed a great degree of wealth. Many other professional relationships did not blossom to the size of Prigozhin’s multi-billion dollar empire. It was perhaps a measure of his friendship with Putin. However, a not so apparent or expected development at the time was a considerable degree of control and power Prigozhin chose to exercise over assets Putin made available to him. In this way, Prigozhin’s handling of money from Putin was indeed quite different than theirs. Prigozhin became exceptionally hands-on at the Wagner Group. Seemingly lost upon him was the reality was that everything came from Putin. As aforementioned, Putin went to some pains to explain that he was the engine behind the Wagner Group as well as Prigozhin’s lucrative Concord. Without Putin, the Wagner Group would never have existed, at least in the robust form that it did by 2023. As for his presence in the newsmedia, Prigozhin had far exceeded what could have been called high-profile. His role had become disastrous within the Wagner Group and for the Russian Federation government. As admitted in previous posts and in the introduction of this essay, Prigozhin was largely in the right when he complained about the inept handling of combat operations and the astronomical loss of Russian Federation troops and contract fighters in Ukraine.

Putin tried to mitigate matters by regaining control of the professional aspects of his relationship with Prigozhin as they concerned the Wagner Group. Particularly after the Wagner Group Rebellion, Putin insisted more than once that Wagner Group troops sign an oath of loyalty to the Russian Federation and contracts with the Russian Federation Defense Ministry. Rather than cooperate, Prigozhin rejected the idea of signing oaths and agreement as he did when it was first broached in early June 2023. He publicly expressed his concern he would lose control of “his” organization to the Defense Ministry and especially his nemesis Shoigu. He did not view resting formal control of the Wagner Group to the government as a shift of control to Putin. The friendship between Putin and Prigozhin had surely gone off the rails. There was much on Putin’s plate at the time, but his troublles with Prigozhin were doubtlessly frustrating, worrisome, and angering.

As noted earlier in Part 1, Prigozhin had lost perspective completely. By the end, he was out of control. He was not “acting”, putting on a show, which very well may have been part of the image he publicly presented during the Wagner Group Rebellion as discussed in greatcharlie’s July 1, 2023 post entitled “The Wagner Group Rebellion: Insurrection or Staged Crisis? A Look Beyond the Common Wisdom (Part 2)”. Prigozhin was being his true self.

Respecting Boundaries

Cuiusvis est errare, nullius nisi insipientes, in errore perseverare. (To err is inherent in every man, but to persist in error takes a fool.) There are limits, boundaries in relationships which should not crossed. Normally, among the mature, those boundaries do not need to be put forth. Often there are those seemingly drawn to violate those boundaries, consciously despite knowing the consequences. Those individuals are poor choices for friends. There also those who may violate those boundaries of friendship unconsciously. (In civilized societies, advanced countries, a consequence for the violation of such boundaries of friendship should not be death. That would be unacceptable behavior, unreasonable, and typically against established law.) One or the other may have been the case with Prigozhin. Month after month, he trampled so aggressively on the vineyard of friend both he and Putin nutured for more than two decades. Assuredly, he placed himself on dangerous ground with his barage of publicized statements.

There were many close associates, friends, who came with him for the ride onward and upward, to include Prigozhin. Most were kept close even with all of their mistakes. A number of theories have been suggested by greatcharlie in previous posts, particularly Part 1 of this essay, for Putin’s apparent patience. At least publicly, Putin is a devout Russian Orthodox Catholic. At the core of Putin’s faith is the injunction to forgive. Perhaps something about Prigozhin and few others sparked Putin to act to some degree within the stricture of his faith with regard to forgiveness. Perhaps, as suggested in Part 1, the cause for his forgiving nature at times has been his sense of humor. Yet with Prigozhin, specifically, he appeared to display a level of tolerance that even then too many friendly observers appeared against his own self-interests. It was clear to anyone observing worldwide that while Prigozhin rambled on about the special military operation in Ukraine beginning in 2022, Putin would only hold him at arms length.

Perhaps Putin recognized that Prigozhin was too gravely wounded by what transpired in Ukraine that it was beyond his capacity to regulate his behavior on the matter. While greatcharlie has no training or expertise in identifying or diagnosing mental health issues, from its layman’s eye, it appears to have been some prominent symptom from a form of post traumatic stress Prigozhin was suffering that was left untreated. It is possible that Putin understood early on that Prigozhin was not fully aware, or could not comprehend, the trying situation in which he had placed the Russian Federation President. Even greatcharlie would assess without equivocation that Prigozhin went too far. Putin could forgive him no more. He could not save him. It is in this vein the Putin’s comments concerning Prigozhin’s mistakes, made the day after the jet crash, take on additional meaning. A few of those mistakes were discussed in Part 1 of this essay.

Indeed, in Part 1, Putin broke his silence on Prigozhin’s jet crash on August 24, 2023 during a meeting with the head of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic, Denis Pushilin, in the Kremlin. If readers can cast their minds back to Putin’s initial remarks, they may recall that Putin stated: “First of all, I want to express my sincere condolences to the families of all the victims, this is always a tragedy.” Putin went on to say: “I’ve known Prigozhin for a long time, since the early ’90′s.” He described him as “a talented man, a talented businessman.”

Putin intriguingly then added: “He was a man of difficult fate, and he made serious mistakes in life, and he achieved the results needed both for himself and when I asked him about it–for a common cause, as in these last months.” There were indeed many mistakes that Prigozhin made while ostensibly assisting Putin. Prigozhin had required but had not always warranted Putin’s forgiveness many times. Putin had forgiven much. To that extent, such is not so apparent as Putin mentioned that Prigozhin always did what he asked him to do. Often, Putin had to hold him at arms length. The list of disappointments is far lengthier than one might imagine as it concerned the failure to optimally serve Putin’s interests. It went far beyond Prigozhin’s ramblings about Ukraine. A small number are listed here.

Surely, Prigozhin was aware that in the Russian Federation or anywhere else in the world, he may have chosen to go, without the protection of Putin, he would have had little chance of survival against a considerable number of adversaries. Doing anything to lose Putin’s protection would have been tantamount to suicide. (Of course, if any had decided to harm Prigozhin while he was under Putin’s protection, nothing could have done to change what may have had occurred. However, certainly Putin would have used available resources to retaliate aggressively.) Still, despite the great meaning Putin’s protection as well as financial support meant for Prigozhin’s survival, he bizarrely proceeded to denigrate Putin’s special military operation, and consequently, the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, the Russian Federation General Staff, and ministers and senior generals leading those organizations.

Prigozhin’s ego not intellect very likely convinced him that his attacks upon Shoigu and Gerasimov and the special military operation following the Wagner Group Rebellion were well-nuanced, laser focusing attention those matters. They were not well-nuanced. They were in greatcharlie’s humble judgment, insultingly obvious. To that extent, Prigozhin could not fathom the degree to which he dangerously undermined his dear friend and dear leader. To consider the matter in even more simplistic terms,, maybe in his mind, all Prigozhin was doing was something akin to taking his toys and leaving Ukraine. However, to Putin, and in fact in reality, the Wagner Group and all that Prigozhin possessed belong to him. One might imagine that in Putin’s mind, the successful and wealthy Prigozhin, a Russian oligarchs, was his creation, his Frankenstein.

In a way, through his last moves on the grand stage and certainly through many of his previous “mistakes” as Putin described his fumbles on the national and international scene, Prigozhin was actually exercising power over the Russian Federation President. He squeezed dry all that energized the bond of friendship between the two men. As these situations sometimes go–based on word of rare survivors, it is possible that when Prigozhin found himself hurtling to the ground in his catastrophically disabled lear jet–if he survived the alleged grenade blast, he may had an epiphany. He may have finally realized that he had gone too far with his public, dysregulated behavior. Rules are rules. Everyone in the Russian Federation at his level knew them with regard behavior toward Putin’s interests and he broke them He broke the rules repeatedly.

Although not directly paralleling the story-line of the erstwhile relationship between Putin and Prigozhin, pertinent conceptually is the plot of Lohengrin a Romantic opera in three acts composed and written in 1848 by Wilhelm Richard Wagner (May 23, 1813 to February 13, 1883). As mentioned previously in Part 1, Wagner was a German composer, conductor, and ptolemicist, known mainly for his operas. Lohengrin premiered in Weimar, Germany, on August 28, 1850 at the Staatskapelle Weimar under the direction of Franz Liszt, the father-in-law, close friend and early supporter of Wagner. Wagner himself was unable to attend the first performance, having been exiled because of his part in the 1849 May Uprising in Dresden. The story is derived from the Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach, a medieval German romance, and its sequel Lohengrin, inspired by the epic of Garin le Loherain. It is part of the Knight of the Swan legend. Set in Antwerp during the first half of the 10th century, the story’s plot revolves around Elsa, the daughter of King Heinrich of the Brabant dynasty. Briefly, in Act I, Elsa has been accused by the evil Ortrud of murdering her own brother, Gottfried, the heir to the dynasty. Ortrud is the wife of Count Telramund, giving her standing to level such an accusation. However, it is revealed that Gottfried was not killed by Elsa but enchanted by Ortrud. When King Heinrich arrives in Antwerp from a journey, he insists upon an explanation for the difficulties that have beset Brabant. Beweeping her outcast state, Elsa dreams of a knight in shining armor who will rescue her. Called to defend herself, she prays and manifests a knight, who arrives in a boat guided by a swan. The knight, Lohengrin, pledges his loyalty to Elsa on the condition that she never questions his name or origin (“Nie sollst du mich befragen, noch Wissens Sorge tragen, woher ich kam der Fahrt, noch wie mein Nam’ und Art!”). Challenged by Telramund, Lohengrin defeats but does not kill him with his sword. Thereby, Elsa’s innocence is established and Lohengrin becomes her defender. In Act II, the malevolent Ortrud and the shamed and banished Telramund conspire to seek revenge. Ortrud tries to sow seeds of doubt in Elsa’s mind, but Elsa responds with innocence and extends friendship to Ortrud. When Lohengrin is named the guardian of Brabant, Telramund in response quietly marshals noblemen to plot against him. In Act III, Elsa and Lohengrin are being wed, but Ortrud and Telramund arrive at the cathedral entrance, seeking to disrupt the wedding. Ortrud alleges that that Lohengrin is an impostor. Telramund accuses him of sorcery. Elsa remains faithful despite the doubts. Afterward, in their bridal chamber, Elsa and Lohengrin express their love, but Elsa’s growing doubts cause her to inquire about her husband’s origins and identity. Suddenly, Telramund and his co-conspirators break in. In the struggle that ensued, Telramund is killed by Lohengrin. Then, returning to Elsa’s inquiry, Lohengrin reveals that his home is the distant temple of the Holy Grail at Monsalvat (“In fernem Land”), that his father is Parsifal, and his name is Lohengrin. Yet, as a result of what has transpired, Lohengrin must return to his sacred home, abandoning Elsa. With prayers, he returns Elsa’s brother, Gottfried, who was actually the swan that led Lohengrin’s boat to human form, and declares him Duke of Brabant. A dove descends from heaven and, taking the place of Gottfried at the head of Lohengrin’s boat and then departs. Ortrud rejoices over Elsa’s betrayal, but meets her demise, sinking into the lake. While calling for her departed husband, Elsa, as Lohengrin forwarned, collapses lifeless, having violated the conditions of his union with her.

Whatever may have actually transpired, much as the aforementioned Lohengrin of Wagner opera sought to protect Elsa from spiritual death, Putin was unable to protect Prigozhin from his indiscretions, from himself. To describe it in a less graceful way,, Prigozhin became a figurative rogue elephant, stomping through the higher realms of Russian Federation foreign and national security policy, trampling on all of working being done by the Kremlin to get a handle on the Ukraine matter.

Prigozhin at Troyekurovskoye cemetary in St. Petersburg in April 2023 (above). Prigozhin was aware that in the Russian Federation or anywhere else in the world, he may have chosen to go, without the protection of Putin, he would have had little chance of survival against a considerable number of adversaries. Doing anything to lose Putin’s protection would have been tantamount to suicide. (Of course, if any had decided to harm Prigozhin while he was under Putin’s protection, nothing could have done to change what may have had occurred. However, certainly Putin would have used available resources to retaliate aggressively.) Still, despite the great meaning Putin’s protection as well as financial support meant for Prigozhin’s survival, he bizarrely proceeded to denigrate Putin’s special military operation, and consequently, the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, the Russian Federation General Staff, and ministers and senior generals leading those organizations. Prigozhin’s ego not intellect very likely convinced him that his attacks upon Shoigu and Gerasimov and the special military operation following the Wagner Group Rebellion were well-nuanced, laser focusing attention those matters. They were not. They were in greatcharlie’s humble judgment, insultingly obvious. To that extent, Prigozhin could not fathom the degree to which he dangerously undermined his dear friend and dear leader.

Prigozhin’s Denouement

Erat hiems summa. (It was the very depth of winter.) As aforementioned, on the first occasion Putin spoke of Prigozhin’s jet crash, he stated: “I’ve known Prigozhin for a long time, since the early ’90′s.” He went on to describe him as a “talented businessman” but added that he had “complicated fate.” To many, those remarks were likely perceived at first glance as a small commentary. They may have been easily overlooked. However, the comments were small much as the small movement of the needle of an old style seismogragh would indicate that a great earthquake was occurring. If Putin had anything to do with Prigozhin’s jet crash, taking such a step would hardly have been something he wanted to do. He unlikely would have done anything harsh against him if he thought that he had some alternative.

Additionally as aforementioned, Putin sought to quell matters by taking control of the professional aspects of his relationship with Prigozhin as they concerned the Wagner Group. The method devised was to have Wagner Group troops sign an oath of loyalty to the Russian Federation and contracts with the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, thereby giving his government reigns over organization and giving Prigozhin nothing to complain about. However, the time had passed for anything such as that with him. Other than that tack, the system in the Russian Federation that he spent 25 years to shape provided no alternatives for Prigozhin’s behavior. There could only be one boss.

Putin, being human, is allowed to feel sadness. However, what is churning in his Iinner-self is hardly stuff for public view and consideration. Surely, Putin has a morbid fear of his enemies at home and abroad getting the chance to peek, to gaze within on him. He would likely assess the possibilities of how they could use observations of such to harm him as limitless. Still, there was the crack in his armor, only for a brief moment is his comments on Prigozhin’s jet crash made on August 24, 2023, that spoke volumes about his long-time connection to his former friend.

Of course, Putin has a need to mask any sense in those he directs, those he through force must control, and perhaps those he holds at bay, that he has weaknesses, that he is human. Such that would typically be recognized as virtue in others, would be a liability,, anathema to him, under his circumstances. To that extent, Putin never appears tortured at all about his circumstances. He has never appeared suffocated by decisions that require aggressive act as most national leaders are not so much effected by such.

It may have been decided among the most powerful in Moscow that if Prigozhin had to be “put down”, it would need to be done in a way that would have a sound educational effect on all others whose loyal, even friendship, toward Putin was uncertain. In a CNBC report dated August 24, 2023, former US Navy Admiral James Stavridis, who served as NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander from 2009 and 2013, said Prigozhin’s death was a dog whistle to those who dissent from Putin’s absolute rule. He added: “He [Putin] needed to demonstrate who really is running the joint.” Stavridis described the attack as a “public execution.” He went on further to state: “No real surprise here, it’s a marker of how lethal, and how deadly and how unscrupulous Vladimir Putin is.”

The same CNBC report included that statement to MSNBC from Ben Rhodes, a tormer deputy national security adviser in the administration of US President barack Obama, explaining that the attack “was not a mysterious accident.” He continued: “This has all the hallmarks of appearing like a military-style takedown,” Rhodes added that Prigozhin’s fate was eminent following a short-lived mutiny about two months ago.

It would seem that missed by Prigozhin was the possability that he may have been brought back from Moscow by the prearrangement of those who would perform the highly clandestine task of terminating him. As greatcharlie is in the dark regarding the truth of the matter, it supposes in the abstract that Prigozhin was much disturbed by whatever information from Moscow that got him to reportedly rapidly board his private jet to get there. One might presume the subject of the communicate concerned the well-being of the Wagner Group. The matter would likely have been made more grave if it had been the case that he was called to meeting of a very senior political authority. Prigozhin being Prigozhin may have rushed to Moscow to demand a meeting with a senior political authority. So far, no mention has been publicly reported on a meeting set between a very senior political authority and Prigozhin, Whether a meeting was set with a considerably senior political authority or an impromptu was insisted upon by Prigozhin would not have been important in this case. Important would have been getting Prigozhin back to his country. Whatever communication was sent to him in Africa managed to get that ball rolling. Patria est ubicumque est bene. (The homeland is where there is good.) Á peine dans ce cas.

One might imagine that those individuals performing the hypothetical heinous task may have been aware through a flight plan or calculations that Prigozhin would leave Moscow in the direction toward St. Petersburg Yet, in the end, as alluded to earlier, how the murderous task may have been carried out is not important. The ones who ordered the act and, to an extent, those physically committed the act, and why it was done is of greater significance. As of the time of this writing, it seems unlikely that any urgency or any effort at all is being placed into finding answers on those points is underway in the Russian Federation or in Western capitals.

Mostly lost in the discussion of Prigozhin’s jet crash was the loss of Dmitry Utkin. In the nascent years of the Wagner Group, he was the face of the organization. The military acumen of the decorated former Spetsnaz officer that served to shape the Wagner Group into a formidable force. Utkin, who seldom spoke publicly and offered no notable opinions about the special military operation in Ukraine or the Russian Federation Defense Ministry–at least nothing negative, nonetheless suffered the same fate of Prigozhin. It may have been a case of guilt by association in the truest sense of the term.

Putin, hand on head, taking a moment to think matters through (above). Behind the scenes in the higher realms of politics and power in the Russian Federation there very well could be individuals actually conspiring against not only Prigozhin but Putin in some silent, convoluted way to to seek revenge. There may have been an effort to sow seeds of doubt in Putin’s mind about Prigozhin, in response to which for the lonest time possible he reject believeing in Prigozhin’s innocence and went a bit further by extends friendship to him after the Wagner Group Rebellion. The somewhat obvious suggestion might be that Shoigu desperate to rid himself of the annoying Prigozhin, slowly but surely wore away at Putin’s trust in him. This idea was initially hinted at in greatcharlie’s July 31, 2023 post entitled, “The Wagner Group Rebellion: Insurrection or Staged Crisis? A Look Beyond the Common Wisdom (Part 1).

Cui Bono?: Flights of Fancy?

As in Act II of the aforementioned Lohengrin, behind the scenes in the higher realms of politics and power in the Russian Federation, mutatis mutandis, there very well could be individuals much as Ortrud and Telramund who were actually conspiring against not only Prigozhin but Putin in some silent, convoluted way to to seek revenge. There may have been an effort to sow seeds of doubt in Putin’s mind about Prigozhin, in response to which for the lonest time possible he reject believeing in Prigozhin’s innocence and went a bit further by extends friendship to him after the Wagner Group Rebellion. The somewhat obvious suggestion might be that Shoigu desperate to rid himself of the annoying Prigozhin, slowly but surely wore away at Putin’s trust in him. This idea was hinted at in greatcharlie’s July 31, 2023 post entitled, “The Wagner Group Rebellion: Insurrection or Staged Crisis? A Look Beyond the Common Wisdom (Part 1)”

In national capitals, Shoigu has been known for his equanimity and sangfroid. He has been described in most accounts by analyst, experts, and newsmedia commentators internally and externally as a discreet and reliable confidant of Putin to the extent one could be. He has managed the Russian Federation Defense Ministry for over a decade. Recognizably, given evidence of the challenges of the special military operation his ministry has faced, he has not proven to be the most qualified one in wartime. As explained in Part 1, Shoigu, much as Prigozhin, never received formal military training. He was appointed to the rank of major general in the National Guard by Russian Federation President Boris Yeltsin in 1991 toward the end of events associated with the coup d’état attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev was launched in Moscow by the self-proclaimed Gosudárstvenny Komitét Po Chrezvycháynomu Polozhéniyu (State Committee on the State of Emergency). Shoigu did not graduate from the Omsk Higher Military School, the Frunze Military Academy, or the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Russian Federation. Shoigu spent nearly a decade as the Minister of Ministestvo po Delam Grazhdanskoy Oborony, Chrezvychainym Situatsiyam i Likvidtsil Posledstviy Bedstviy (Ministry of the Russian Federation for Affairs for Civil Defense, Emergencies and Elimination of Consequences of Natural Disasters Emergency Situations also known as the Ministry for Emergency Situations) or EMERCOM. In November 2012, Putin appointed Shoigu as Russian Federation Defense Minister.

Prigozhin is not the only one who for whatever reason was moved out of the way of Shoigu as they were ostensibly a hindrance to his efforts to achieve success in Ukraine. General-Colonel Aleksandr Zhuravlev, who headed Russia’s Western Military District since 2018 was sacked in September 2022 He was deemed ineffective. General Aleksandr Dvornikov was labelled the first senior commander but not the overall commander of all of Russian Federation’s operations in Ukraine. He was sacked between July and September 2022. Colonel General Gennady Valeryevich Zhidko, who commanded the Southern forces fighting in Ukraine was sacked in September 2022 due to the lack of progress and significant losses in his area. He died suddenly in 2023. Lieutenant General Roman Berdnikov, who commanded Russian Federation forces in the Donbas or Western Grouping. Berdnikov was held responsible for the chaos that ensued within Russian lines after Ukrainian troops recaptured swathes of territory in its September 2022 offensive in the east. Colonel General Rustam Muradov, who commanded Russia’s Eastern Military District, and was placed in charge of leading an offensive in the Ukrainian city of Vuhledar, in the eastern Donbas region, was removed from his post in February 2023. Interestingly, the Institute for the Study of War, a think tank based in Washington, D.C. reported in a March 9, 2023 assessment of the Ukraine War that Shoigu ordered Muradov to take Vuhledar “at any cost” in order “to settle widespread criticism within the Russian Ministry of Defense about the lack of progress and significant losses in the area.” Russian Air Force General Sergei Surovikin was replaced by Gerasimov as commander of the Joint Group of Forces in the Special Military Operation zone in Ukraine. In a January 11, 2023 statement from the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, it was explained that Gerasimov’s appointment constituted a “raising of the status of the leadership” of the military force in Ukraine and was implemented to “improve the quality . . . and effectiveness of the management of Russian forces”. Surovikin became Gerasimov’s deputy commander in the Southern “Grouping”. At the start of the Wagner Rebellion on June 23, 2023, Surovikin was detained by the security services and was reportedly released some time in September 2023. Then of course there was Prigozhin.

Given how many Russian Federation senior military commanders have been sacked by Shoigu with Putin’s blessing of have suddenly died away from the battlefield since the special militsry operation began, one might argue that it is uncertain whether he will emerge the winner in his ostensible struggle to stay top and in good stead and uncertain whether he is simply a survivor weaken severely by endless internal maneuvers. With Prigozhin out of the way, Shoigu was made better able to direct the Wagner Group not around the world–a mission that may be maintained–but in Ukraine in a way that satisfies him. Many served in the Russian Federation’s spetsnaz units and possess exquisite military capabilities in stealthy hit-and-run direct actions, special reconnaissance, counterterrorism, and covert operations. Shoigu will likely take the organization’s troops and use them essentially as infantry formation with no greater tasks than those of basic infantry units.

Left with few or no rivals, for the first time, Shoigu stands exposed. He will unlikely be able future mistakes and failures on others. He made find himself stalling Russian Federation forces or creating great difficulties for them against repeated Ukrainian counteroffensives or rapid defeat. It is unlikely that he along with Gerasimov could completely manipulate Putin, get him to move wildly in a new, unplanned direction. Plainly, they lack the faculty to manipulate him or develop any bold plans. It is nearly assured Putin would reject any inordinate plans and see them straight as the .inept leaders they are. He would either warn them off tactfully, or respond ruthlessly to their potential crass subterfuge.

In the abstract, one might consider the possibility that beyond the forward edge of the political battlefield n the Russian Federation are those who sought to separate Prigozhin from Putin. Such powerful individuals, hiding behind the façade of respectability, have considered what the transition from Putin to a new leader might appear. Their number would doubtlessly be kept small as they would surely want to eliminate the possibility of being detected over inordinate levels of communication. With a silent hand, perhaps they have already begun to shape events hoping to ensure any future transition in leadership would favor their interests. To that extent in this hypothetical situation, Prigozhin loyal to Putin and quite formidable, could have potentially posed a threat in response to any plans and audacious moves that they might make at a given time. He certainly no. onger poses any threat to them Such ideas are purely speculative, but not so fanciful that they are unworthy of some modicum of consideration. This is not meant to suggest or hint that such individuals would have carried out or had a hand in the death of Prigozhin. Rather, through their means to influence others and a few subtle efforts, they may have caused the ball to begin to roll in the right direction.

There is the possibility that the cause of Prigozhin’s death was multifactorial, having, involving, or produced by a compound of hostile elements mentioned here, creating a bizarre murderous, synergistic effect. Perhaps one might speculate that Prigozhin did not really have a chance of living beyond August 23, 2023, the fated point of confluence.

Whatever may have transpired, it seems Putin was unable to protect Prigozhin from himself. He became a figurative rogue elephant, stomping through the higher realms of Russian Federation foreign and national security policy, trampling on all of the work being done by the Kremlin to get a handle on the Ukraine matter.

Putin (left) meeting with Russian Federation Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov (1st right) and with Andrei Troshev, a former Wagner Group commander (2nd right) on September 28, 2023 in the Kremlin. Putin’s inner circle, though one man short, generally seems no worse for wear. Dare one say, the entire environment is quite a bit less noisy as a consequence of Prigozhin’s demise. However, efforts to replace Prigozhin and Utkin and rejuvenate what remains of the Wagner Group will likely pose some problems for the immediate future Efforts by Putin to reinvigorate the organization in some effective form have been public. Readers may cast their minds back to reports that on September 29, 2023, Putin met with a number of former senior commanders of the Wagner Group ostensibly to discuss how “volunteer units” could best utilized in Ukraine. On state television, Putin was shown meeting Russian Federation Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov and with Andrei Troshev, a former Wagner Group commander known by the cognomen, “Sedoi” (Grey Hair) on September 28, 2023 in the Kremlin. The trick for Putin’s newly appointed leaders would be to put the pieces of Wagner Group back together again to his satisfaction without Prigozhin’s charisma and special touch, and the force of Utkin’s reputation as a fighting leader. Back in June 2023, the Wagner Group’s troop strength was tens of thousands. As aforementioned, it is widely understood in the Russian Federation that since the Wagner Group Rebellion, that many Wagner Group veterans have joined other private military companies and have returned to Ukraine under individual contracts with Russian Federation Defense Ministry. Some of the Wagner fighters have signed up for service with the Russian Army.

The Impact of Prigozhin’s Loss to the Wagner Group Appears Greater than Putin Estimated

Putin’s inner circle, though one man short, generally seems no worse for wear. Dare one say, the entire environment is quite a bit less noisy as a consequence of Prigozhin’s demise. However, efforts to replace Prigozhin and Utkin and rejuvenate what remains of the Wagner Group will likely pose some problems for the immediate future Efforts by Putin to reinvigorate the organization in some effective form have been public. Readers may cast their minds back to reports that on September 29, 2023, Putin met with a number of former senior commanders of the Wagner Group ostensibly to discuss how “volunteer units” could best utilized in Ukraine. On state television, Putin was shown meeting Russian Federation Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov and with Andrei Troshev, a former Wagner Group commander known by the cognomen, “Sedoi” (Grey Hair) on September 28, 2023 in the Kremlin.

Yevkurov, a few months prior to the meeting, had reportedly travelled to several countries where Wagner mercenaries have operated. Troshev, a decorated veteran of Russia’s wars in Afghanistan and Chechnya and a former commander in the SOBR interior ministry rapid reaction force, is from St Petersburg, Putin’s home town. He was awarded Russia’s highest medal, Hero of Russia, in 2016 for the storming of Palmyra in Syria against ISIS militants. Both men were pictured with Putin in the television broadcast.

In the video of the meeting, Putin addresses Troshev stating that they had spoken about how “volunteer units that can perform various combat tasks, above all, of course, in the zone of the special military operation.” He continued: “You yourself have been fighting in such a unit for more than a year,” Putin went further: “You know what it is, how it is done, you know about the issues that need to be resolved in advance so that the combat work goes in the best and most successful way.” Additionally, Putin remarked that he wanted to speak about social support for those involved in the fighting. No comments were heard from Troshev during the broadcast. Following the meeting, Russian Federation Presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov told the Russian Federation’s RIA news agency that Troshev had become a Russian Federation Defense Ministry official. The publicized Kremlin meeting appeared to signal at that juncture that the Wagner Group would be directed by Troshev and Yevkurov.

The trick for Putin’s newly appointed leaders would be to put the pieces of Wagner Group back together again to his satisfaction without Prigozhin’s charisma and special touch and the force of Utkin’s personality and reputation as a fighting leader. Back in June 2023, the Wagner Group’s troop strength was tens of thousands. As mentioned in Part 1, it is widely understood in the Russian Federation that just before and especially after the Wagner Group Rebellion, many Wagner Group veterans reportedly joined other private military companies and have returned to the fight in Ukraine under individual contracts with Russian Federation Defense Ministry. Some of the Wagner fighters signed up for service with the Russian Army. Sources from the United Kingdom’s military intelligence have explained: “The exact status of the redeploying personnel is unclear, but it is likely individuals have transferred to parts of the official Russian Ministry of Defence forces and other PMCs [private military companies].”

What greatcharlie assessed at the time as an extraordinary turn of event, six days after the start of the Wagner Group Rebellion, Prigozhin and 34 commanders of his Wagner Group, who only a week before were dubbed mutineers and treasonous by Putin in four very public addresses in June 2023, met with the Russian Federation President in the Kremlin on June 29, 2023. The Kremlin confirmed the meeting occurred. According to the French newspaper Libération, Western intelligence services were aware of the momentous occasion, but they insist the meeting transpired on July 1, 2023. Two members of the Security Council of the Russian Federation attended the meeting: the director of Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki (Foreign Intelligence Service) or SVR, Sergei Naryshkin, and the director of Rosgvardiya (the National Guard of Russia) Viktor Zolotov. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told reporters: ““The commanders themselves outlined their version of events, emphasizing that they are soldiers and staunch supporters of the head of state and the supreme commander-in-chief.” Peskov continued: “They also said that they are ready to continue fighting for the motherland.”

Some readers may recall Putin’s rather gracious speech concerning the Wagner Group Rebellion given on June 27, 2023, in which he focused on the future disposition of Wagner Group. He did not indicate at the time that there would be further problems for its members ahead. Putin wanted to inform the Russian people about the remedy he came upon for handling the Wagner Group troops and their leaders. Covering what was already known through the Russian Federation’s state-run and independent newsmedia that day, he explained that those Wagner Group troops who had participated in the rebellion were free to go to Belarus. He also confirmed that those who wished to continue in the fighting in Ukraine could sign contracts with the Russian Federation Defense Ministry. However, Putin then mentioned a step that was an odd twist beyond simply signing contracts with the Defense Ministry. He invited the former Wagner Group “mutineers” to sign contracts with law enforcement or the security services. Putin stated: “I express my gratitude to those Wagner Group soldiers and commanders who had taken the right decision, the only one possible–they chose not to engage in fratricidal bloodshed and stopped before reaching the point of no return.” He then said: “Today, you have the opportunity to continue your service to Russia by signing a contract with the Defence Ministry or other law enforcement or security agency or return home.” It was ostensibly a rather gracious opening of doors of the government’s defense and security services to rebels who he initially created the impression in his address of being associated with a conspiratorial and reckless leadership. Unexpectedly, Putin added to all he said on matter the statement, “I will keep my promise.” Imaginably, that was presumed. Perhaps it should not have been.

In the minds of the Wagner Group troops, they had already pledged their allegiance to the Russian Federation not only in words but with the shedding of their blood. They watched their Wagner Group comrades die on many battlefields on foreign lands for the Russian Federation. Imaginably, in their minds, they were free and independent fighting men, not longer serving in the Russian Federation Armed Forces. The allegiance of the Wagner Group appeared to be unambiguous to the Kremlin

However, as hinted on in Part 1 of this essay, dealing with Putin often means hearing promises from him that were not sure at all. Putin turned on his promises to merely maintain his trust in the loyalty of Wagner Group troops. Putin made it crystal clear following the death of Prigozhin that he was unwilling to brook further opposition to his will from anyone in the organization.

After August 25, 2023, volunteer fighters working on behalf of the Russian Federation were required to swear an oath to the Russian Federation flag. A decree was signed by Putin on that very day, which was just two days after the death Prigozhin. According to the Kremlin website, the oath applied to groups “contributing to the execution of tasks given to the armed forces”–members of volunteer formations, private military contractors–and territorial defense units. The website went on to state: “Fighters were required to pledge “their loyalty to the Russian Federation . . . strictly follow their commanders and superiors’ orders, and conscientiously fulfill their obligations.” The step was allegedly designed to help in the “forming the spiritual and moral foundations for the defense of the Russian Federation.” Not every volunteer fighter was a Russian Federation citizen, so the oath was a considerable requirement for many. Prigozhin strenuously objected to the idea of a loyalty oath when it was first suggested believeing it would essentially bring about the end of the Wagner Group. When asked about the future of the Wagner Group at the time of the decree was signed, Peskov made the surprising and shocking public statement that: “legally the Wagner private military group does not exist.”

Wagner Group Headquarters in St. Petersburg (above) In the minds of the most Wagner Group troops, they had already pledged their allegiance to the Russian Federation not only in words but with the shedding of their blood. They watched their Wagner Group comrades die on many battlefields on foreign lands for the Russian Federation. Imaginably, in their minds, they were free and independent fighting men, not longer serving in the Russian Federation Armed Forces. The allegiance of the Wagner Group appeared to be unambiguous to the Kremlin. Putin promised as much in speeches and meetings with Wagner Group commanders and officials. However, as hinted on in Part 1 of this essay, dealing with Putin often means hearing promises from him that were not sure at all. Putin turned on his promises to merely maintain his trust in the loyalty of Wagner Group troops. Putin made it crystal clear following the death of Prigozhin that he was unwilling to brook further opposition to his will from anyone in the organization. After August 25, 2023, volunteer fighters working on behalf of the Russian Federation were required to swear an oath to the Russian Federation flag. A decree was signed by Putin on that very day, which was just two days after the death Prigozhin. Prigozhin strenuously objected to the idea of a loyalty oath when it was first suggested believeing it would essentially bring about the end of the Wagner Group. When asked about the future of the Wagner Group at the time of the decree was signed by Putin, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov made the surprising and shocking public statement that: “legally the Wagner private military group does not exist.”

The Way Forward

Western Russian Federation analysts and experts and mainstream newsmedia on commentators on foreign affairs have often been frightfully querulous about Putin’s decisions and actions to the point at which some have more occasionally appeared dysregulated. That has had no constructive impact upon their assays on his management of complex issues in which the Russian Federation is involved. In their public the aforementioned assessments, analysts, experts, and commentators typically include observations of him behaving in ways that are abberant.

The rather dramatic way in which Putin had distanced himself from staffs and guests at the Kremlin during a following the COVID-19 pandemic–it is uncertain whether Putin still engages in this practice–is popularly pushed out by the Western newsmedia as evidence of some unusual, unhealthy shift in his thinking. On this popular point, greatcharlie conversely suggests there is the real possibility that unbeknownst to all but those closest to Putin that he was successfully poisoned recently, and his extremely cautious behavior has been spurred on by such an unpleasant, perhaps life-threatening, episode. If such a hypothesized event occurred in truth, having his most senior advisers, in photographs and videos of meetings in the Kremlin, sit rather naturally though seated somewhat distant from him would surely be more understandable. Certainly, they would be fully understanding and support his need and efforts to show greater vigilance for his personal safety. Yet, returning to Western perspectives, what makes Putin’s behave appear strange can be viewed as enough to go as far as to conclude he cannot be judged as a trustworthy interlocutor and reliable party to any talks.

The relatively efficient functioning of the Russian Federation government is dependent upon Putin’s strong presence, hands-on management, and dynamic leadership. Surely, no one in Putin’s inner circle would feel too comfortable facing the world without him. (Imaginably, some observers in the West might dismissively and facetiously remark that in Putin’s world, they have little choice to do otherwise.) Additonally, if a life-threatening incident actually occurred sometime recently, it might expected that HIS personal security detail–to the extent that anyone might insist Putin do anything–would insist upon dramatic precautions such as the very seating arrangements in Kremlin that the world has observed.

Without pretension, greatcharlie states that it never presumed that the discussion here would offer the degree of clarity or stimulate a degree of lucidity that would allow readers through insights presented to unravel the truth of the mystery of Prigozhin’s jet crash. Perhaps for some it strangely enough has. However, with regard to Putin In many ways, the course of his relationship with Prigozhin holds up a mirror to the nature of his relationships not only within his inner circle, but with the Russian people and with foreign allies and partners

Putin generally seeks to develop personal bonds among national leaders and greater bilateral ties where there at best can be mutual interests and goals from a position of strength. He will be generous as part of his efforts foster relations at those various levels, but holding superior position always remains paramount. In that course, Putin will emphasize boundaries .Putin has appeared tolerant of their occasional violation, but ultimately he has acted in response of such. An exception to this course would be China with which the Russian Federation only holds a stronger position due to its nuclear arsenal. That could potentially change in the near future but that remains to seen.. The US is not a friend of the Russian Federation. Under the best circumstances, Putin over the years has sought cordial ties, an entente cordiale with it.

As was the case with Prigozhin, after losing Putin’s “trust”, countries seeking to reach some reasonable and sustainable agreement with him on anything should only expect subterfuge and betrayal. Capitals in the West are not ignorant of this reality. Based on all that has been presented to Moscow by the West, it does not appear that any constructive end state is apparent. To that extent, nothing go is reasonably expected. Moreover, what appears uncertain with them is how far things might go with Putin’s behavior. The danger of the situation is compounded by the fact that Putin doubtlessly views the conflict with Ukraine as a conflict between the Russian Federation with the US and its NATO allies. The conflict may be one fought indirectly by the two sides, the Rubicon has been crossed. The die has been cast. As military theorists and planners in the 20th century, many long departed, calculated decades ago, a conflict of this kind could put the East and West on a collision course in a nuclear way.,The best hope to avoid that would having the reasonable take steps right now. However, it would seem the Russian Federation is not being led by wholly reasonable thinkers. Looking back, their choice to invade Ukraine, and carry out military operations in the way they did, was truly counterintuitive.

While many may rebuff and reject what is stated here, greatcharlie remains firm in its belief that the course of relations between the Russian Federation with the US, the rest of the West, eastern powers other than China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea that the current vector of policy is toward eventual disaster. The only aspect unknown to all but clairvoyants is the timing of a future conflict. If greatcharlie is in not in error, and the reality of Putin’s attitude and behavior escapes political authorities in the US and its allies following this episode between Putin and Prigozhin discussed here, they are displaying a disregard for their respective countries’ self-interests which is daylight madness. Analysts and forecasters in the foreign and national security bureaucracies in Western countries who find such an outcome too difficult to imagine and would prefer continuing to proffer assessments under which Putin would eventually submits to the will of the US and its allies–pardon greatcharlie’s frankness–are simply whistling in the wind. Only realistic thinking and planning on the matter may bring forth viable solutions if any exist. Solum ut inter ista certum sit nihil esse certi. (In these matters the only certainty is that there is nothing certain.)