The US Central Command (CENTCOM) Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at Al-Udeid Air Base, Qatar (above). It is comprised of a joint US military and Coalition team that executes day-by-day combined air and space operations and provides rapid reaction, positive control, coordination, and deconfliction of weapons systems. On September 17, 2016, CAOC was monitoring a Coalition airstrike over Deir Ezzor when Russian Federation forces informed it that the attack was hitting a Syrian military position. The attack impacted a US diplomatic effort with Russia on Syria.

According to a November 29, 2016 New York Times article entitled, “Unintentional Human Error Led to Airstrikes on Syrian Troops, Pentagon Says,” the US Department of Defense identified “unintentional” human mistakes as the causality for the US-led airstrikes that killed dozens of Syrian government troops in September 17, 2016. The strikes occurred as a deal to ease hostilities in Syria, brokered by the US and Russia, was unraveling. They particularly undercut US Secretary of State John Kerry’s diplomatic efforts with Russian Federation Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to coordinate the US and Russian air campaigns over Syria. Russian Federation military units, which were working closely with the forces of Syrian Arab Republic President Bashar al-Assad to fight ISIS and other rebels, said the attack had killed 62 Syrian troops and wounded more than 100. The attack marked the first time the US had engaged the Syrian military since it began targeting the ISIS in Syria and Iraq two years ago. It was determined as result of the investigation, led by US Air Force Brigadier General Richard Coe, that the attack was conducted under the “good-faith belief” that the targets were ISIS militants. It also concluded that the strikes did not violate the law of armed conflict or the rules for the US military. Danish, British and Australian forces also participated in the airstrike. Coe said, “In my opinion, these were a number of people all doing their best to do a good job.”

As Kerry was engaged in a crucial effort to persuade Russia to coordinate its air campaign in Syria with similar US efforts when the airstrike occurred, greatcharlie has been fogged-in over why the risky attack was ever ordered. In a previous post, greatcharlie stated that Russian Federation military commanders could benefit greatly from working alongside US air commanders and planners. It was also suggested that the US might provide a demonstration of its targeting and operational capabilities to encourage Russia’s cooperation. However, the errant attack was certainly not the sort of demonstration greatcharlie had in mind. On better days, US air commanders and planners have demonstrated a practically unmatched acumen in using air assets of the US-led coalition’s anti-ISIS air campaign to shape events on the ground in support of the goals of US civilian leaders. US air commanders and planners have very successfully conducted No-Fly Zones and sustained air campaigns over the past three decades, in Bosnia, Yugoslavia, Kosovo, where political goals endured, and in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya.

Those experienced enough in life fully understand that it has its promises and disappointments. Whether events go well or negatively for one, an authentic truth is revealed in the outcome from which valuable, edifying lessons as well as new ideas can be extrapolated. The errant bombing of September 17, 2016 and findings of the investigation of it have come late in the administration of US President Barack Obama. Too little time is really available for lessons from the incident to influence any remaining decisions that the administration might make on Syria or military coordination and cooperation with Russia. The subsequent collapse of the negotiations on military coordination may have assured such decisions would not be required. Yet, for the incoming US administration, they may offer some useful hints on negotiating military coordination and cooperation with Russia on Syria or other countries on other issues if the opportunity arises. A few of those lessons are presented here with the hope they might mitigate the potential of an unfortunate military incident as witnessed in Syria that might also derail a crucial diplomatic effort. The overall hope is that the next administration will be tended by an honorable peace. Quidquid ages, prudenter agas et respice finem! (Whatever you do, do cautiously, and look to the end!)

The airstrike undercut US Secretary of State John Kerry’s (right) diplomatic effort with Russian Federation Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (left) to coordinate the US and Russian air campaigns over Syria. Bringing Russia over to the US view was already dicey. A few days before the incident, the US and Russia exchanged charges of noncompliance with a ceasefire agreement reached on September 12th in Geneva.

This Was Not the Demonstration of US Capabilities Imagined

The Obama administration may not have actually been enthused about working with Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin on Syria, but it recognized that Russia, with its considerable military investment in Syria, can play an important role in ending the war. To that extent, it sought to have Putin agree to have agreement crafted by Kerry and Lavrov to cooperate militarily. The agreement called for formation of a US-Russia Joint Implementation Center to coordinate strikes against ISIS as well as Al-Qaeda affiliated Islamic militant forces after there had been seven consecutive days of reduced violence in the civil war and humanitarian aid had begun to flow to besieged communities in Syria. Bringing Russia over to the US view was already dicey enough. A few days before the incident, the US and Russia exchanged charges of noncompliance with the ceasefire agreement that Kerry and Lavrov reached on September 12, 2016 in Geneva.

On August 20, 2016, greatcharlie suggested the US could increase the value of its assistance through an actual demonstration of US capabilities to further encourage a change in Putin’s perspective on Kerry’s proposal on military cooperation. Included among recommendations was providing Putin with a complete US military analysis of the setbacks Russia and its allies have faced in Syria, and the relative strengths and weakness versus their Islamic militant opponents. The exact manner in which intelligence resources the US proposed to share with Russia and US military resources would have been of value to Russia could have been demonstrated by targeting and destroying a number battle positions of ISIS and other Islamic militant groups in Syria. Where possible, US airstrikes could have disrupted and destroyed developing attacks and counterattacks against Russia’s allies. Through a video of the attacks, Putin could have been shown how the unique capabilities of US weapons systems could enhance the quality of Russian airstrikes. He might also have been provided with US military assessments of those attacks.

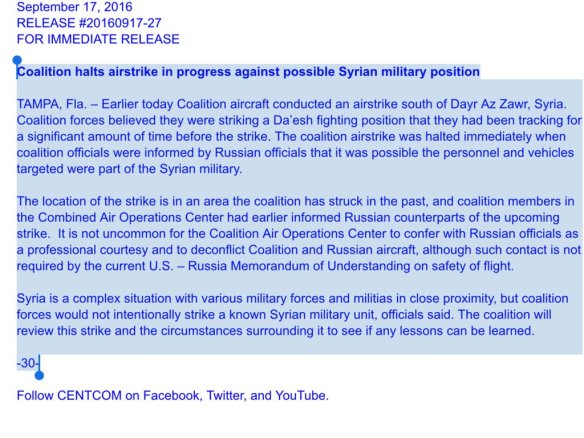

The US Central Command (CENTCOM), which oversees US military operations in the Middle East, told the Russians in advance about the planned strike on an airfield in Deir Ezzor Province, calling it a “professional courtesy.” A senior US official said the Russians had acknowledged the message, thereby assuring they would the audience for the US attack. However, after the attack, the Russians had no reason to express appreciation or compliments to CENTCOM. The strike began in the early evening of the next day. According to Russia, two A-10s, two F-16 fighters, and drones of the US-led Coalition were deployed to attack the airfield. They began hitting tanks and armored vehicles. In all, 34 precision guided missiles were erroneously fired on a Syrian Arab Army unit. The attack went on for about 20 minutes, with the planes destroying the vehicles and gunning down dozens of people in the open desert, the official said. Then, an urgent call came into CENTCOM’s Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at Al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar, which provides command and control of air power throughout Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and 17 other nations. The Russians relayed to the CAOC the disappointing news that the US strike was hitting Syrian forces. Four minutes later, the strikes were halted.

A “bombed up” A-10 Thunderbolt II fighter (above). In the early evening of September 17, 2016, two pairs of Coalition A-10 and F-16 fighters along with drones were deployed to attack an airfield in Deir Ezzor. They began hitting tanks and armored vehicles. In all, 34 precision guided missiles were erroneously fired on a Syrian Arab Army position. The attack lasted about 20 minutes, with the fighters destroying the vehicles and gunning down dozens of Syrian troops in the open desert. If not halted, the entire Syrian unit might have been wiped out.

In Syria over 95 percent of Russian Federation Air Force sorties are flown at 15,000 to 20,000 feet primarily to evade enemy air defenses. As aircrews cannot identify targets, bombs are dropped in areas where air intelligence reports the enemy is located. In attacking urban centers, that can result in collateral damage in the form of civilian deaths and injuries and the destruction of nonmilitary structures. US Permanent Representative to the UN, Samantha Power pointed to the issue of targetting by Russian Federation Air Force and Syrian Arab Air Force jets. On September 17, 2016, Power stated the Syrian government, assisted by Russia, has tortured and bombed its people. She added, “And, yet, in the face of none of these atrocities has Russia expressed outrage, nor has it demanded investigations, nor has it ever called for . . . an emergency meeting of the Security Council” on a Saturday night or any other night.

Air intelligence provides commanders with information on enemy targets to the extent that visual searches of enemy targets is no longer required. Given the speed of fighters and the need to protect aircrews and aircraft from anti-aircraft weapons and other arms, flying at lower altitudes with the goal of identifying targets by visual search is no longer feasible. Even friendly forces are often required to mark targets with flags or smoke for their own safety. US air commanders ordered the attack in the proximity of Syrian forces, calculating that the conclusions of air intelligence about the target were accurate. Informing aircrews that they would be operating in close proximity to Syrian troops did not create any requirement for them to engage in a time consuming, very hazardous, visual search of the target before going into their attack. Nevertheless, as US Air Force Lieutenant General Jeffrey Harrigian, the commander of US Air Forces and Combined Forces Air Component in CENTCOM aptly explained, “In this instance, we did not rise to the high standard we hold ourselves to, and we must do better than this each and every time.”

The Russian Federation armed forces and intelligence services use their intelligence tactics, techniques, procedures, and methods to meet the needs of air commanders and planners. However, over 95 percent of Russian Federation Air Force sorties in Syria are flown at 15,000 to 20,000 feet primarily to evade air defenses. Bombs are dropped where air intelligence reports state the enemy is located. Attacks in urban centers have resulted in civilian deaths and injuries and the destruction of nonmilitary structures.

Intelligence Analysts Erred

The Russian Federation armed forces and intelligence services proudly use their own intelligence tactics, techniques, procedures, and methods to meet the needs of commanders and planners. Russian Federation commanders and planners would certainly like to believe that by intensifying their own intelligence gathering activities, they can achieve success without US assistance. However, the summer of 2016 proved to be particularly difficult for Russian Federation forces and their allies as progress eastward toward Raqqa and Deir Ezzor was slowed. ISIS was able to apply pressure, infiltrating into areas retaken by the allies and launching counterattacks. The fight for Aleppo became a greater strain than anticipated. Beyond human intelligence collection–spies, the US gathers continuous signal and geospatial intelligence over Syria. Those multiple streams of intelligence could assist Russian Federation commanders and planners in pinpointing ISIS and other Islamic militant groups on the ground even if they are dispersed. Air assets of the Russian Federation and its allies could destroy them, disrupt their attacks, and support ground maneuver to defeat them. In support of the proposal, Kerry and Lavrov already agreed that a map could be drawn up indicating where Islamic militant forces are positioned. They also agreed that US and Russian military personnel working in the same tactical room would jointly analyze the intelligence and select targets for airstrikes.

Reportedly, US surveillance aircraft had been watching the erroneously-labelled Syrian unit for several days. According to a redacted copy of a report that summarized the investigation, a drone examined an area near an airfield in Deir Ezzor Province in eastern Syria on September 16, 2016, identifying a tunnel entrance, two tents and 10 men. The investigation found that those forces were not wearing recognizable military uniforms or identification flags, and there were no other signs of their ties to the Syrian government. On September 17, 2016, a CENTCOM official, who at the time requested anonymity because the incident was still being investigated, said military intelligence had already identified a cluster of vehicles, which included at least one tank, as belonging to ISIS. Coe stated, “In many ways, these forces looked and acted like the Daesh forces the coalition has been targeting for the last two years,” using the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State.

In a statement on the investigation of the incident, CENTCOM outlined a number of factors that distorted the intelligence picture for the airstrike. Included among them were “human factors” such as “confirmation bias”; “improper labelling”; and invalid assumptions. The Syrian Arab Army unit observed at Deir Ezzor was wrongly identified or labelled as ISIS early in the analytical process. CENTCOM’s statement indicated that incorrect labelling colored later analysis and resulted in the continued misidentification of the Syrian unit on the ground as ISIS. Further, the statement laid out a series of changes to the targeting process that the Defense Department has already made to include more information-sharing among analysts. The US Air Force has independently placed its process for identifying targets under review.

Qui modeste paret, videtur qui aliquando imperet dignus esse. (The one who obeys with modesty appears worthy of being some day a commander.) What appears to have been needed at the time beyond issues concerning tactics, techniques, procedures and methods for conducting air operations was better coordination of its own diplomatic and military activities regarding Syria. As a sensible precaution, US air commanders and planners should have been informed that operations conducted at that time could have considerable positive or negative impact on US diplomatic efforts in Syria. (The publicized record of the investigation does not touch on this point.) The delicate nature of diplomacy would have been factored into planning, not shrugged off. Interference by civilian leaders in military units’ tactical operations is surely not desired by commanders. Yet, by failing to call attention to the unique political and diplomatic environment in which they were operating over Syria, the matter was left open to chance.

MQ-1 Predator drone (above). Reportedly, US surveillance aircraft had been watching the erroneously-labelled Syrian military position for several days. A drone examined an area near an airfield in Deir Ezzor Province on September 16, 2016, identifying a tunnel entrance, two tents and 10 men. The investigation found that those forces were not wearing recognizable military uniforms or identification flags, and there were no other signs of their ties to the Syrian government.

Confirmation Bias and Hormones: Decisionmaking on the Airstrikes

Decipimur specte recti. (We are deceived by the appearance of right.) In the conclusions of the US Defense Department’s investigation, causality for the incident was found to be in part the thinking of US air commanders and planners. It was determined to have been a bit off-kilter and confirmation bias was pointed to specifically. Confirmation bias is a result of the direct influence of desire on beliefs. When individuals desire a certain idea or concept to be true, they end up believing it to be true. They are driven by wishful thinking. This error leads the individual to cease collecting information when the evidence gathered at a certain point confirms the prejudices one would like to be true. After an individual has developed a view, the individual embraces any information that confirms it while ignoring, or rejecting, information that makes it unlikely. Confirmation bias suggests that individuals do not perceive circumstances objectively. An individual extrapolates bits of data that are satisfying because they confirm the individual’s prejudices. Therefore, one becomes a prisoner of one’s assumptions. The Roman dictator Gaius Julius Caesar has been quoted as saying “Fene libenter homines id quod volunt credunt,” which means, “Men readily believe what they want to believe.” Under confirmation bias, this is exactly the case. Attempting to confirm beliefs comes naturally to most individuals, while conversely it feels less desirable and counterintuitive for them to seek out evidence that contradicts their beliefs. This explains why opinions survive and spread. Disconfirming instances must be far more powerful in establishing truth. Disconfirmation requires searching for evidence to disprove a firmly held opinion.

Cogitationem sobrii hominis punctum temporis suscipe. (Take for a moment the reasoning of a quiet man.) For the intelligence analyst, appropriately verifying one’s conclusions is paramount. One approach is to postulate facts and then consider instances to prove they are incorrect. This has been pointed to as a true manifestation of self-confidence: the ability to look at the world without the need to look for instances that pleases one’s ego. For group decision-making, one can serve a hypothesis and then gather information from each member in a way that allows the expression of independent assessments. A good example can found in police procedure. In order to derive the most reliable information from multiple witnesses to a crime, witnesses are not allowed to discuss it prior to giving their testimony. The goal is to prevent unbiased witnesses from influencing each other. US President Abraham Lincoln intentionally filled his cabinet with rival politicians who had extremely different ideologies. At decision points, Lincoln encouraged passionate debate and discussion.

At the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, research is being done to better understand the biological basis for decisionmaking using lab experiments and biological data. Some of the findings of research scientist, Gideon Nave, who came to Wharton from the university’s neuroscience department, prove as relevant to this case as much as confirmation bias. Nave explains that the process of decision-making is influenced by their biological state. Factors that can influence that biological state naturally include hunger, sleep deprivation and stress. However, Nave is also looking deeper at the influence of hormones on decision-making. In dominant situations, different hormones fluctuate in people. For example, stress creates a clearly measurable biological stress response that consists of elevation of several hormones in our body. Nave has focused on noradrenaline and cortisol. Cortisol specifically affects decisionmaking.

In examining decisionmaking, Nave recognizes that people trade-off by people accuracy and speed when making decisions. Cortisol, Nave has found, influences people’s will to give the simple heuristic, or “gut answer” faster, as if they were under time pressure. There is a simple test Nave uses through which one can observe their own responses. It come in the form of a math word problem. There is a bat and a ball for the US sport baseball. Together, they cost $1.10. Now, the bat costs a dollar more than the ball. What’s the price of the ball? More often than not, individuals tested will give their intuitive answer. Indeed, as the ball is 10 cents, and the bat is $1 more, they typically believe it means that the bat is $1.10, so together the bat and ball would be $1.20. However, that would be incorrect. The correct answer is 5 cents and $1.05. When the answer 10 cents is given, it usually has not been thought through. There is no time limit set for providing an answer. There is no incentive offered by the tester for answering with speed. It seems the only real pressure is the desire of an adult, who may be paid for being correct at his or her job, and may be achievement oriented, to correctly answer what is an elementary school-level math woth word problem with speed and confidence.

In analysis at the tactical level, target identification can require splitting-hairs. Much as a bank teller dispensing cash, a mistake by an intelligence can lead to a crisis. Doubt and uncertainty can be mitigated with sufficient, timely redundant assessments. In a sensitive political and diplomatic environment as the one faced in Syria, the slightest uncertainty should have been cause enough to deliberate and think through a target’s identification. While normally action-oriented, in a sensitive political and diplomatic environment, the commander, for that brief period, could order unit commanders and planners exercising caution in targeting and launching attacks.

In anew initial statement (above), CENTCOM, still uncertain, recognized the possibility that Syrian forces were hit in Deir Ezzor. For the intelligence analyst, verifying one’s conclusions is paramount. One approach is to postulate facts and then consider instances to prove they are incorrect. It requires the ability to look at the world without the need to look for instances that pleases one’s ego. For group decision-making, one can set a hypothesis and gather information from each member, allowing for the expression of independent assessments.

Ensuring the Right-hand and the Left-hand Know What the Head Wants

Perhaps civilian leaders in the Obama administration failed to fully consider or comprehend issues concerning measures used to identify and decide upon targets. Perhaps they were unaware that it was more important in that period of intense negotiations with Russia to minimize or simply avoid attacks on targets in close proximity to the forces of Russia and its allies. Under ordinary circumstances, the matter could reasonably be left for Russia commanders in the field to handle without concern for any implications in doing so. If in the future, an effort is made to demonstrate to Russia the best aspects of US capabilities and the benefits enjoyed by US-led Coalition partners in operations against ISIS and Al-Qaeda affiliated Islamic militant forces, some guidance regarding urgent political goals for that period, and the need for enhanced diligence and perhaps restraint in the conduct of operations must be issued. It was either determined or no thought was given to reviewing and approving relevant procedures and initiatives at a time when crucial diplomatic efforts needed to be, and should have been, supported.

Historia magistra vitae et testis temporum. (History is the teacher and witness of times.) During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, civilian leaders recognized the need for enhanced diligence and perhaps restraint in the conduct of a Naval blockade of Cuba. The effort US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to inform US Chief of Naval Operations Admiral George Anderson of that resulted in a renowned angry exchange between them. The sources on which Graham Allison relied upon in the original edition of his seminal work on the crisis, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (Little, Brown and Company,1971), claimed that the US Navy failed to implement the President John Kennedy’s orders to draw the blockade like we closer to Cuba ostensibly to give the Soviet Union’s calculating Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Nikita Khrushchev, more time to decide to half Soviet ships, and that Anderson resisted explaining to McNamara what procedures the Navy would use when intercepting the first Soviet ship to approach the line.

According to Allison’s account of the confrontation between McNamara and Anderson, US President John Kennedy was worried that the US Navy, already restive over the controls imposed on how the blockade of Cuba was to be executed, might “blunder into an incident.” McNamara was closely attuned to Kennedy’s worries and resolved to press the Navy leadership for additional information on its modus operandi. Confronting Anderson, McNamara minced no words: “Precisely what would the Navy do when the first interception occurred?” Anderson told him that he had already covered that same ground before the National Security Council, and the further explanation was unnecessary. This answer angered McNamara, proceeded to lecture Anderson on the political realities: “It was not the President’s design to shoot Russians but rather to deliver a political signal to Chairman Khrushchev. He did not want to push the Soviet leader into a corner; he did not want to humiliate him; he did not want to risk provoking him into a nuclear reprisal. Executing the blockade is a an act of war, one that involved the risk of sinking a Soviet vessel. The sole purpose of taking such a risk would be to achieve a political objective. But rather than let it come to that extreme end, we must persuade Chairman Khrushchev to pull back. He must not be ‘goaded into retaliation’.” Getting the feeling that his lecture did not sink in, McNamara resumed his detailed questioning. Whereupon Anderson, picked up the Manual of Naval Regulations, waved it in McNamara face and shouted, “It’s all in there!” McNamara retorted, “I don’t give a damn what John Paul Jones would have done. I want to know what you are going to do, now!”

Other sources that Allison utilized claimed that civilian leaders believed US antisubmarine warfare operations included using depth charges to force Soviet submarines to surface, raising the risk of inadvertent war. According to Richard Betts in American Force: Dangers, Delusions and Dilemmas in National Security (Columbia University Press, 2011). Subsequent research indicated that these stories were false. Indeed, Joseph Bouchard explains in Command in Crisis: Four Case Studies (Columbia University Press, 1991) that McNamara actually ordered antisubmarine procedures that were more aggressive than those standard in peacetime. Harried civilian leaders may not have fully comprehended the implications of all these technical measures, or may have had second thoughts. Nevertheless, the relevant procedures and initiatives did not escape their review and approval.

US President John Kennedy (left) with US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (right). During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, civilian leaders recognized the need for enhanced diligence in the conduct of a Naval blockade of Cuba. McNamara’s effort to inform the US Navy of that resulted in a renowned exchange between himself and the Chief of Naval Operations, US Navy Admiral George Anderson. Well before the errant Syria airstrike, civilian leaders should have told US air commanders and planners of their operations’ potential to impact crucial, ongoing US diplomatic efforts.

The Way Forward

In William Shakespeare’s comedy, The Tempest, Prospero, the rightful Duke of Milan, although forced to take refuge on an island for twelve years after his brother Antonio seized his title and property, refused to use his extraordinary powers, magic, to take revenge when the opportunity presented itself. Prosperous remarks, “The rarer action is in virtue than in vengeance.” The best definitions of virtue can be found among teachings of various religions. However, to avoid being impolitic by choosing one religion and its tenants over others, its definition can be drawn from philosophy. From a philosophical perspective, virtue is well-defined by the “Golden Mean” proffered by Cleobulos of Lindos, one of the Seven Sages of Greece. The Golden Mean manifested an understanding that life is not lived well without following the straight and narrow path of integrity. That life of moderation is not what is popularly meant by moderation. The classical Golden Mean is the choice of good over what is convenient and commitment to the true instead of the plausible. Virtue is then the desire to observe the Golden Mean. Between Obama and Putin, no confidence, no trust, no love existed, and relations between the US and Russia have been less than ideal. Regarding the errant Syria airstrike, the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the UN, Vitaly Churkin, said it perhaps served as evidence of US support for ISIS and an al-Qaeda affiliate fighting the Syrian government which the US sought to remove. Churkin’s statement could be viewed as indicaing that insinuated into his thinking was the notion commonly held worldwide of the US as virtuous country, a notion proffered, promoted, and purportedly fashioned into its foreign policy. It appears that he, too, would have liked to believe US actions and intentions are guided by virtue. Yet, it would seem that was a hope unfulfilled as a result of the bombing Syrian troops, coupled with all the disagreements and disputes, trials and tribulations between the US and Russia, and led to his expression of so much disappointment and discouragement. Nihil est virtute pulchrius. (There is nothing more beautiful than virtue.)

The US must be a role model, a moral paragon as the world’s leader acting as virtuously as it speaks. The US leaders must act virtuously not just because others worldwide expect it, but rather because they should expect it of themselves. Diplomatic relations with Russia must be transformed in line with a new policy necessitating efforts to end misunderstandings and to exploit opportunities in which the two countries can coordinate and cooperate. However, achieving that will require the effective stewardship of US diplomatic, military, political, and economic activities by US leaders. Micromanagement can often result in mismanagement in certain situations. Still, in the midst of on-going efforts to resolve urgent and important issues, US leaders must take steps to ensure that all acting on behalf of the US. They must thoroughly understand the concept and intent of the president, the implications of any actions taken individually or by their organizations, and perform their tasks with considerable diligence. All must make a reasonable effort to ensure errant actions are prevented. Melius est praevenire quad praeveniri. (Better to forestall than to be forestalled.)