Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin (above). Putin, himself, appears to be the cause for difficulties that the Trump administration has encountered in improve relations between the US and Russia. One might accuse Putin of playing a cat and mouse game with Trump. Why Putin would act in this manner is uncertain. An assay of Putin from outside the box may provide a framework from which the Russian President’s complexities can be better understood.

According to a March 3, 2018 New York Times article entitled, “A Russian Threat on Two Fronts Meets an American Strategic Void”, US President Donald Trump has remained silent about his vision to contain Russian power, and has not expressed hope of luring Moscow into new rounds of negotiations to prevent a recurrent arms race. Indeed, the article, largely critical of the Trump administration, explains that “most talk of restraint has been cast to the wind” over the past few months. What purportedly envelopes Washington now is a strategic vacuum captured by “Russian muscle-flexing and US hand-wringing.” A cyberchallenge has enhanced the degree of tension between the two countries. The article reports that top US intelligence officials have conceded that Trump has yet to discuss strategies with them to prevent the Russians from interfering in the midterm elections in 2018. In striking testimony on February 27, 2018 on Capitol Hill, the director of both the US National Security Agency and the US Cyber Command, US Navy Admiral Michael Rogers explained that when he took command of his agencies, one of his goals was to assure that US adversaries would “pay a price” for their cyberactions against the US that would “far outweigh the benefit” derived from hacking. Rogers conceded in his testimony that his goal had not been met. He dismissed sanctions that the US Congress approved last year and those that Trump had not imposed as planned would not have been enough to change “the calculus or the behavior” of Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin.

What was reported by the March 3rd New York Times article presaged a shaky future for US-Russian relations. At the start of the Trump administration, Putin convincingly projected an interest in working toward better relations through diplomacy. Areas of agreement and a degree of mutual respect between Trump and Putin have been found. Yet, agreements reached should have served to unlock the diplomatic process on big issues. Putin appears to be the causality for a figurative draw on the scorecard one year into the Trump administration’s exceptionally pellucid, well-meaning effort. Putin seems to be playing a cat and mouse game with Trump–constant pursuit, near capture, and repeated escapes. It appears to have been a distraction, allowing him to engage in other actions. While engaged in diplomacy, the Trump administration has observed hostile Russian moves such as continued interference n US elections, as well as other countries, and efforts to support Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and to tighten Moscow’s grip Crimea and the Donbass. Those actions greatly diverge with US policies on Syria and Ukraine. Putin and his officials have shown their hand too completely over time for anyone in Washington to allow themselves to be seduced by Putin’s guise of wanting to improve ties. In the recent greatcharlie post, it was explained that Trump and foreign and national security policy officials in his administration, who were good-naturedly referred to as “stone hearts”, were well-aware from the get-go that Putin and his government could more often than not be disingenuous. If Putin truly does not want positive to change in relations, the Trump administration’s diplomatic project with Russia is likely moribund. If there were some touch that Trump could put on the situation right now that would knock the project in the right direction, he certainly would. At the moment, however, the environment is not right even for his type of creativity and impressive skills as a negotiator. For now, there may very well be no power in the tongue of man to alter Putin. Since no changes in relations are likely in the near future, it would be ideal if Putin would avoid exacerbating the situation between the US and Russia by suddenly halting any ongoing election meddling. The whole matter should have been tied-off and left inert in files in the Kremlin and offices in the Russian Federation intelligence and security services. However, Putin seems to going in the opposite direction. The threat exists that Putin, seeing opportunity where there is none, will engage in more aggressive election meddling, and will also rush to accomplish things in its near abroad, via hybrid attacks at a level short of all out war, with the idea that there is time left on the clock before the US responds with a severe move and relations with the Trump administration turn thoroughly sour. That possibility becomes greater if the Kremlin is extrapolating information to assess Trump’s will to respond from the US newsmedia.

Putin’s desire, will, and ability to act in an aggressive manner against the US, EU, and their interests must be regularly assessed in the light of new events, recent declarations, and attitudes and behaviors most recently observed by Western leaders and other officials during face to face meetings with him. Undoubtedly, Trump is thoroughly examining Putin, trying to understand him better, mulling through the capabilities and capacity of the US and its allies to respond to both new moves and things he has already done. Since Trump is among the few Western leaders who have recently met with Putin–in fact he has met with him a number of times, there might be little unction for him to be concerned himself with meditations on the Russian President made in the abstract. Nevertheless, an assay of Putin from outside the box may provide a framework from which the Russian President’s complexities can be better understood. Parsing out elements such as Putin’s interests and instincts, habits and idiosyncrasies, and the values that might guide his conscious and unconscious judgments would be the best approavh.to take. A psychological work up of that type on Putin is beyond greatcharlie’s remit. However, what can be offered is a limited presentation, with some delicacy, of a few ruminations on Putin’s interior-self, by looking at his faith, pride, ego; countenance, and other shadows of his soul. What is presented is hardly as precise as Euclid’s Elements, but hopefully, it might be useful to those examining Putin and contribute to the policy debate on Russia as well. Credula vitam spes fovet et melius cras fore semper dicit. (Credulous hope supports our life, and always says that tomorrow will be better.)

Putin has publicly declared his faith and has been an observant member of the Russian Orthodox Church. By discussing his faith, Putin has developed considerable political capital among certain segments of the Russian public. Putin’s political opponents and other critics at home, however, would question where faith has its influence on him given some of his policy and political decision, particularly concerning territorial grabs, overseas election meddling, and reported human and civil rights violations in his own country.

Faith

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines faith as complete trust or confidence; a strong belief in a religion, based on spiritual conviction rather than proof. Faith guides the mind. It helps the mind conclude things. Simple faith, involves trusting in people and things. Communists mocked faith in the church, but still had faith in Marx. In that vein, faith allows for the acceptance of the word of another, trusting that one knows what one is saying and that one is telling the truth. The authority being trusted must have real knowledge of what he or she is talking about, and no intention to deceive. Faith is referred to as divine faith when the one believed is God. In discussing Putin’s divine faith, greatcharlie recognizes that to convey a sense of religiousness makes oneself spooky to some. Writing publicly, one of course opens oneself up to constructive criticism at best and obloquy at worst. Still, a discussion tied to faith might be feared by readers on its face as being one more expression of neurotic religiosity, an absurdity. That presents a real challenge. Nonetheless, the effort is made here.

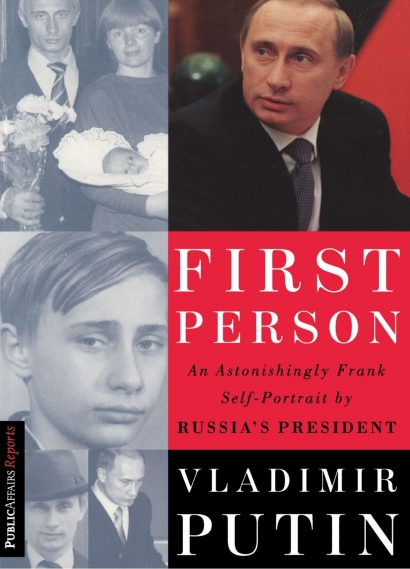

Putin has publicly declared his faith on many occasions. He has been an observant member of the Russian Orthodox Church. Putin was introduced, to religion, faiith, and the church early in his life. In Part 1 of Putin’s 2000 memoir, First Person: An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia’s President (Public Affairs, 2000), Putin explains that his mother, Mariya Ivanovna Shelomova, attended church and had him baptized when he was born. She kept his baptism a secret from his father, who was Communist Party member and secretary of a party organization in his factory shop. Putin relates a story concerning her faith as well as his own in Part 1’s final paragraph. He explains: “In 1993, when I worked on the Leningrad City Council, I went to Israel as part of an official delegation. Mama gave me my baptismal cross to get it blessed at the Lord’s Tomb. I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since.” Religious formation must start at childhood discussing ideas as being kind, obedient, and loving. They must be told of the world visible and invisible. Children are buffeted by many aggressive, strange, harmful ideas, and must able to surmount them by knowing what is right and doing what is right. Children tend to gravitate toward prayer, which strengthens their faith and helps their devotion grow. One tends to resemble those in which one is in regular conversation, and prayer helps bring children closer to God. The very brief life God bestows to one on Earth is lived more fully with faith. On his death bed, the renowned French philosopher, playwright, novelist, and political activist, Jean Paul Sartre, stated: ”I do not feel that I am the product of chance, a speck of dust in the universe, but someone who was expected, prepared, prefigured. In short, a being whom only a Creator could put here, and this idea of a creating hand refers to God.” Est autem fides credere quod nondum vides; cuius fidei merces est videoed quod credis. (Faith is to believe what you do not see the reward of this faith is to see what you believe.)

Faith does not replace the intellect, it guides the mind. Whether Putin’s faith has shaped his views or his Ideology is unclear. By discussing his faith, Putin has developed considerable political capital among certain segments of the Russian public. It has allowed Putin to cloak him in something very positive, very healthy, and would provide citizens with a good reason to doubt and dismiss negative rumors and reports about his actions. Many Russian citizens have responded to Putin’s introduction of faith to the dialogue about his presidency by coming home to the Orthodox Church. Perhaps that is a positive aspect that can be found in it all. Members of Russia’s opposition movement and other critics at home, however, would question where faith has its influence on him given some of his policy and political decision, particularly concerning territorial grabs, overseas election meddling, and reported human and civil rights violations in his own country. They would claim that rather than shaping his policy decisions in office, his faith is shaped by politics. They would doubt that he would ever leverage influence resulting from his revelations about his faith in a beneficial way for the Russian people or any positive way in general. They could only view Putin’s declaration of divine worship as false, and that he is only encouraging the superficial worship of himself among the intellectually inmature who may be impressed or obsessed with his power, wealth, lifestyle, and celebrity.

Putin commemorates baptism of Jesus Christ in blessed water (above). On June 10, 2015, Putin was asked by the editor in chief of the Italian daily Corriere della Sera, “Is there any action that you most regret in your life, something that you consider a mistake and wouldn’t want to repeat ever again.” Putin stated, “I’ll be totally frank with you. I cannot recollect anything of the kind. It appears that the Lord built my life in a way that I have nothing to regret.”

Putin is certain that his faith has provided a moral backing for his decisions and actions as Russian President. On June 10, 2015, Putin was asked by the editor in chief of the Italian daily Corriere della Sera, “Is there any action that you most regret in your life, something that you consider a mistake and wouldn’t want to repeat ever again.” Putin stated, “I’ll be totally frank with you. I cannot recollect anything of the kind. It appears that the Lord built my life in a way that I have nothing to regret.”

Having humility means to be honest about ones gifts and defects. The true source, the real hand in ones accomplishments, is God. Once one recognizes this, one can be honest about the need for God’s assistance. Putin’s, to a degree, seems to indicate that he has humility and appears assured that he has been placed in his current circumstances, and has given him the ability to do all that he has done, as the result of God’s will. However, Putin should keep in mind that evil can quiet all suspicions, making everything appear normal and natural to those with the best intentions. To that extent, his decision and actions could truly be the augur of his soul, but perhaps not in a positive way. Evil can go into the souls without faith, into souls that are empty. Once evil insinuates itself in one’s life, there is chaos, one becomes bewildered, confused about life, about who one is. Due to the threat of evil influence one must be willing to look deeper at oneself to discern flaws, to see what is lacking. Having a sense of balance in this world necessitates having an authentic knowledge of oneself, the acceptance of daily humiliations, avoidance of even the least self-complacency, and humble acknowledgement of ones faults. The virtue of temperance allows one to give oneself a good look. Once one gets oneself right, then one can get God right. Vitiis nemo sine nascitur. (No one is born without faults.)

Putin seemingly surmises that he is satisfying God through his religious observance and by obeying religious obligations. Yet, one cannot approach God simply on the basis of one’s “good deeds.” Indeed, simply doing the right things, for example, following the law does, not grant you salvation. It does not give you guidance. Approval, recognition, obligation, and guilt are also reasons for doing good. The motive behind your actions is more important than your actions. To simply believe also does not put one in a position to receive. Your heart must be right.

Putin celebrating Christmas in St Petersburg (above). Wrong is wrong even if everyone else is doing it. Right is right even if nobody is doing it. Putin’s conscience should be able to distinguish between what is morally right and wrong. It should urge him to do that which he recognizes to be right. It should restrain him from what he recognizes to be wrong. Ones conscience passes judgment on our actions and executes that judgment on the soul.

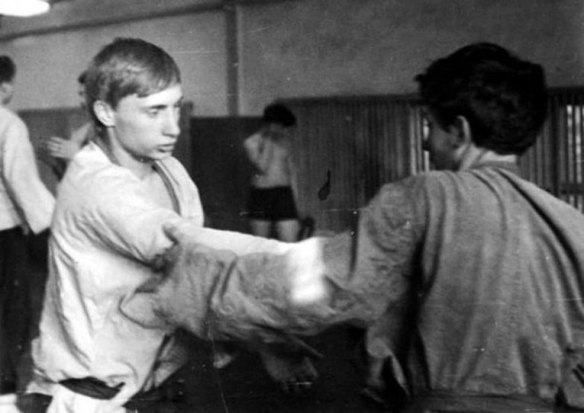

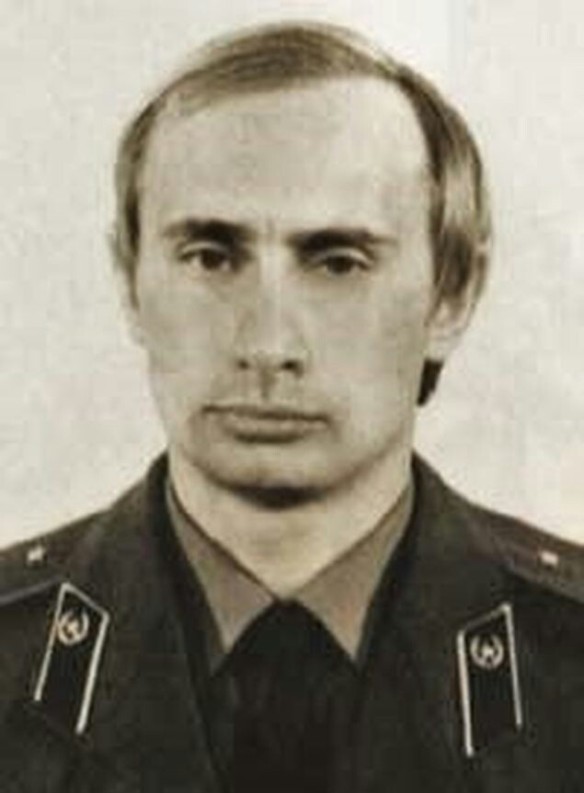

All those who have worked for Putin, and those who have come up against him, would likely agree that he has a wonderful brain, and his intellect must be respected. His talents were first dedicated to his initial career as an officer in the Soviet Union’s Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (the Committee for State Security) known better as the KGB—the agency responsible for intelligence, counterintelligence, and internal security. The job took root in him. As a skilled KGB officer, he was proficient at lying, manipulation and deception. It was perhaps his métier. Putin would likely say he engaged in such behavior for all the right reasons, as a loyal foot soldier. Subsequently, he would serve in a succession of political positions in the intelligence industry that were thrust upon him. In 1997, he served as head of the Main Control Directorate. In 1998, he was ordered to serve as director of the Federal’naya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Federatsi (Russian Federation Federal Security Service) or FSB. Later that same year, he was named Secretary of the Security Council. Through those positions, he was educated thoroughly on the insecurity of the world. It was a world in which things in life were transient. He discovered the width of the spectrum of human behavior. Putin applies that knowledge of humankind, sizing-up, and very often intimidating interlocutors, both allies and adversaries alike. The 16th century English statesman and philosopher, Sir Francis Bacon said that “knowledge itself is power,” but Intellect without wisdom is powerless. One matures intellectually when one moves from seeking to understand the how of things to understanding the why of things. Through the conquest of pride can one move from the how to the why. One can only pray for the wisdom to do so. In The New Testament, Saint Paul explains: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect. For by the grace given to me I say to everyone among you not to think of himself more highly than he ought to think, but to think with sober judgment, each according to the measure of faith that God has assigned. Beatus attempt esse sine virtute nemo potest. (No one can be happy without virtue.).”

The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains that the inclination toward sin and evil is called “concupiscence”. Baptism erases original sin and turns a man back towards God. However, the inclination toward sin and evil persists, and the man must continue to struggle against concupiscence. Sin leads to sin. Acts of sin tend to perpetuate themselves and result in additional acts of sin. Sin can become a way of life if it goes unchecked. When Putin approaches the altar of the Russian Orthodox Church, his purpose should be to expiate sin.

Wrong is wrong even if everyone else is doing it. Right is right even if nobody is doing it. Putin’s conscience should be able to distinguish between what is morally right and wrong. It should urge him to do that which he recognizes to be right. It should restrain him from what he recognizes to be wrong. For the spiritual, conscience is formed by God’s truth. God’s truth creates order. In addition to knowing God’s truth, one must embody His truth which is inspired by love. The truth is a great treasure, a satisfactory explanation of the world and heaven that should speak to the individual. One should love God, love one’s neighbor, and remain virtuous by choice because it is the right thing to do. The reason for ones existence is best understood once one connects with the Creator of life. One can be happy with what makes God happy. Sub specie aeternitatis. (Under the aspect of eternity.)

Ones conscience passes judgment on our actions and executes that judgment on the soul. One should not do things that do not fit one. Conscience will send warning signals ahead of time. One should not ignore ones conscience. One should not violate it. The conscience should serve as Putin’s protection. Despite everything, it could very well be that Putin has a seared conscience. A less sensitive conscience will often fail an individual. Perhaps his conscience is dead. In following, his ability to know what is right may be dead. Putin declared his faith. He did not declare that he was a moral paragon. Quodsi ea mihi maxime inpenderet tamen hoc animo fui semper, ut invidiam virtute partam gloriam, non invidiam putarem. (I have always been of the opinion that infamy earned by doing what is right is not infamy at all, but glory.).

Putin at the 2015 Moscow Victory Day Parade (above). Putin would likely be delighted to know there was a general understanding that his pride and patriotism go hand in hand. To that extent, all of his moves are ostensibly made in the name of restoring Russia’s greatness, to save it from outsiders who have done great harm to the country and would do more without his efforts. Some Russian citizens actually see Putin as ‘the Savior of Russia.”

Pride

Si fractus illabatur orbis, impavidum ferient ruinae. (If the world should break and fall on him, it would strike him fearless.) The OED defines pride as a feeling of deep pleasure or satisfaction derived from achievements, qualities or possessions that do one credit, or something which causes this; consciousness of one’s own dignity or the quality of having an excessively high opinion of oneself. Pride has been classified as a self-conscious emotion revolving around self and as social emotion concerning ones relationship to others. It can be self-inflating and distance one from others.

In terms of being conscious of the qualities, the positive nature of one’s country, surely national leaders must have a cognitive pride, an attitude of pride in their countries, their administrations, and missions. They will express their pride with dignity, regardles of how big or small, powerful or weak, that their countries are. Putin insists that all Russian have pride in their country. Putin wants all Russian citizens to be part of their country’s rise to greatness. Divisions based on race, ethnicity, religion and origin hinder that. It is worth repeating from the greatcharlie post, “Russia Is Creating Three New Divisions to Counter NATO’s Planned Expansion: Does Shoigu’s Involvement Assure Success for Putin?”, that much as the orator, poet, and statesman, Marcus Tullius Cicero, concluded about his Ancient Rome, Putin believes that loyalty to the Russian Federation must take precedence over any other collectivity: social, cultural, political, or otherwise. As noted by Clifford Ando in Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2013), in the hierarchy of allegiances outlined by Cicero, “loyalty toward Rome occupied a superordinate position: her laws and her culture provided the normative fabric that would, to borrow a phrase of Rutilius Namatianus [Poet, Imperial Rome, 5th Century], ‘create from distinct and separate nations a single fatherland’.” Likewise, Russia’s laws and culture provide the normative fabric from which a united country is created from diverse peoples. Possession of citizenship should be the basis to cause individuals to identify with the concerns of others in widely disparate populations among Russia’s republics. Putin wants Russians to be in a “Russian state of mind,” a mental state created when diversity, creativity, and optimism coalesce. A citizen’s attitude, perspective, outlook, approach, mood, disposition, and mindset should stand positively Russian.

From a theological perspective, the prideful individual acts as if their talents, possessions, or achievements are not the result of God’s goodness and grace but their own efforts. When pride is carried to the extent that one is unwilling to acknowledge dependence on God and refuses to submit ones will to God or lawful authority, it is a grave sin. While not all sins source from pride, it can lead to all sorts of sins, notably presumption, ambition, vainglory, boasting, hypocrisy, strife, and disobedience. In that vein, pride is really striving for a type of perverse excellence. That type of pride can be embedded deeply in ones being.

1. Patriotism

Putin’s emotional pride is also expressed in the form of profound patriotism. Patriotism is defined as having or expressing devotion to and vigorous support for ones country. In reading Part 1 of Putin’s First Person, one can begin to understand why patriotism permeates everything Putin does. Given the rich history of his family’s service to the homeland gleaned from his parents and grandparents, it is hard to imagine how he would think any other way. It was gleaned because according to Putin, much of what he learned about his family was caught by him and not taught directly to him. Indeed, he explains: “My parents didn’t talk much about the past, either. People generally didn’t, back then. But when relatives would come to visit them in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), there would be long chats around the table, and I would catch some snatches, so many fragments of the conversation.” Putin’s grandfather, Spiridon Ivanovich Putin, was a cook. However, after World War I he was offered a job in The Hills district on the outskirts of Moscow, where Vladimir Lenin and the whole Ulynov family lived. When Lenin died, his grandfather was transferred to one of Josef Stalin’s dachas. He worked there for a long period. It is assumed by many that due to his close proximity to Stalin, he was a member of the infamous state security apparatus, the Narodnyi Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) or NKVD. Putin notes that his grandfather came through the purges unscathed unlike most who spent much time around Stalin. Putin also notes that his grandfather outlived Stalin, and in his later, retirement years, he was a cook at the Moscow City Party Committee sanatorium in Ilinskoye. As for Putin’s mother, she refused to leave Leningrad as the Germans were blockading it. When it became impossible for her to remain, her brother, under gunfire and bombs, took her out along with her baby, Albert, Putin’s brother, to Smolny. Afterward, she put the baby in a shelter for children, which is where he came down with diphtheria and died. (Note that in the 1930s, Putin’s mother lost another son, Viktor, a few months after birth.) Putin’s mother nearly died from starvation. In fact, when she fainted from hunger, people thought she had died, and laid her out with the corpses. With God’s grace, she awoke and began moaning. She managed to live through the entire blockade of Leningrad.

Putin at the War Panorama Museum in St. Petersburg (above). Patriotism is defined as having or expressing devotion to and vigorous support for ones country. Patriotism permeates everything Putin does. Given the rich history of his family’s service to the homeland gleaned from his parents and grandparents, it is hard to imagine how he would think any other way.

As for Putin’s father, Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin, he was on the battlefield, serving in a NKVD demolitions battalion, engaged in sabotage behind the German lines. There were 28 members in his group. Recounting a couple of experiences during the war that his father shared with him, Putin explains that on one occasion after being dropped into Kingisepp, engaging in reconnaissance, and blowing up a munitions depot, the unit was surrounded by Germans. According to Putin, a small group that included his father, managed to break out. The Germans pursued the fighters and more men were lost. The remaining men decided to split up. When the Germans neared Putin’s father, he jumped into a swamp over his head and breathed through a hollow reed until the dogs had passed by. Only 4 of the 28 men in his NKVD unit returned home. Upon his return, Putin’s father was ordered right back into combat. He was sent to the Neva Nickel. Putin says the mall, circular area can be seen, “If you stand with your back to Lake Ladroga, it’s on the left bank of the Neva River.” In his account of the fight, Putin said German forces had seized everything except for this small plot of land, and Russian forces had managed to hold on to that plot of land during the long blockade. He suggests the Russians believed it would play a role in the final breakthrough. As the Germans kept trying to capture it, a fantastic number of bombs were dropped on nearly every part of Neva Nickel, resulting in a “monstrous massacre.” That considered, Putin explains that the Neva Nickel played an important role in the end.

That sense of pride and spirit Putin seeks to instill in all Russians echoes the powerful lyrics of Sergei Mikhalkov in the National Anthem of the Russian Federation. They are not just words to Putin, they are his reality. As if the vision in Verse 3 could have been written by Putin, himself, it reads: “Ot yuzhykh morei do poliarnogo kraia Raskinulis nashi lesa i polia. Odna ty na svete! Odna ty takaia – Khranimaia Bogom rodnaia zemlia! (Wide expanse for dreams and for living Are opened for us by the coming years Our loyalty to the Fatherland gives us strength. So it was, so it is, and so it always will be!) Putin would likely be delighted to know that there was a general understanding that his pride and patriotism go hand in hand. To that extent, all of his moves are ostensibly made in the name of restoring Russia’s greatness, to save it from outsiders who have done great harm to the country and would do more without his efforts. Some Russian citizens actually see Putin as “the Savior of Russia.”

2. Self-esteem

Pride can cause an individual to possess an inordinate level of self-esteem. They may hold themselves superior to others or disdain them because they lack equal capabilities or possessions. They often seek to magnify the defects of others or dwell on them. The Western country that has been the focus of Putin’s disdain, far more than others, is the US. An manifestation of that prideful attitude was Putin’s response to the idea of “American Exceptionalism” as expressed by US President Barack Obama. In his September 11, 2013 New York Times op-ed, Putin expressed his umbrage over the idea. So important was his need to rebuff the notion of “American exceptionalism”, that he sabotaged his own overt effort to sway the US public with his negative comments about it. The op-ed was made even less effective by his discouraging words concerning US operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. This would not be his last effort to sway the US public on important matters, nor the last one to backfire. Putin is not thrilled by the Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again,” or the concept “America First.” He has expressed his umbrage in speeches and in public discussions. Subordinates such as Russian Federation Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Russian Federation Presidential Spokesperson Dimitry Peskov, using florid rhetoric, have amplified Putin’s views on the matter.

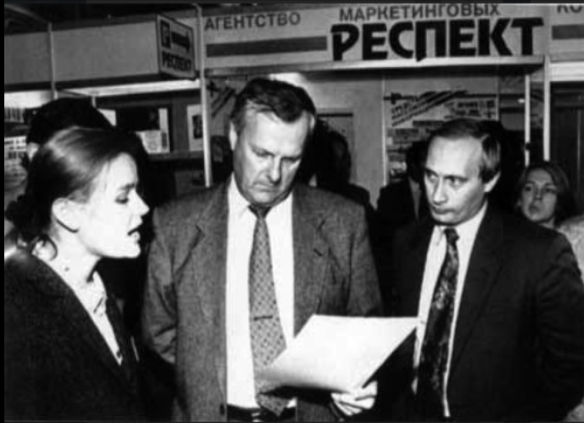

As an officer in the KGB, the main adversary of Western intelligence and security services during the Cold War, Putin would naturally harbor negative sentiment toward his past, now present, opponents. Perhaps if there were some peace dividend at the end of the Cold War that Russia might have appreciated, and his ears were filled by Donna Nobis Pacem (Give US Peace), his attitude may have been different. In fact, the world might never have known Putin, or would known a different one. However, that was not the case. Putin did not inherit an ideal situation in Russia when he became president. While on his way to the top of the political heap, Putin saw how mesmerising “reforms” recommended to Yeltsin’s government by Western experts drastically impacted Russia’s economy in a way referred to somewhat euphemistically by those experts as “shock treatment.” Yeltsin was unaware that Western experts were essentially “experimenting” with approaches to Russia’s economic problems. His rationale for opening Russia up to the resulting painful consequences was not only to fix Russia’s problems but ostensibly to establish comity with the West. The deleterious effects of reforms recommended by Western experts’ could be seen not only economically, but socially. In the West, alarming statistics were reported for example on the rise of alcoholism, drug addiction, birth defects, HIV/AIDS, a decreased birth rate, and citizens living below the poverty line. Russia’s second war in Chechnya which was brutal, and at times seemed unwinnable, had its own negative impact on the Russian psyche. As Russia’s hardships were publicized internationally, perceptions of Russia changed for the worst worldwide. However, Putin saw no need for Russia to lose any pride or surrender its dignity as a result of its large step backward. Putin believed Russia would rise again, and that some acceptable substitute for the Soviet Union might be created, and never lacked faith about that. Putin was loyal and obedient while he served Yeltsin, but saw him tarry too long as Russia strained in a state of collapse.

US President Donald Trump (left) and Putin (right). Intelligence professionals might say that the correct and expected move in response to a covert operation that has failed very publicly, so miserably, would be to “tie it off”. Instead, as reported by US Intelligence agencies and the White House, Russia’s effort to meddle in the US elections has become recursive. Putin declined to be upfront with Trump about the matter. Russia must exit any roads that could lead to disaster.

Putin has not hesitated to use force when he believed there would be some benefit in doing so. Still, he has shown that he would prefer to outthink his rivals in the West rather than fight them. That notion may in part have influenced his responses in contentious situations. It may also account for the sustained peace with the US that Russia has enjoyed under his stewardship. However, it may be possible that this line of thinking was born out of necessity rather than by choice. Except for its long-held, unquestioned ability to engage in a nuclear war with the US, Russia has lacked the capability and capacity to do other big, superpower-type things successfully for nearly three decades. True, Moscow’s Crimea-grab and moves in Eastern Ukraine were swiftly accomplished and significant. Russian Federation military operations in Georgia’s South Ossetia and Abkhazia garnered the full attention of the West. However, both moves, though important, actually caused more disappointment than create a sense of threat to the interests of the US and EU. To that extent, the US, EU, and NATO were not convinced that there was a need for direct military moves in Ukraine to confront Russia, no positioning of NATO troops in Crimea or Eastern Ukraine to counter Russia’s moves, to make things harder for Moscow. To go a step further, there is no apparent balance between Russia’s self-declared role as a superpower and the somewhat moderate military, diplomatic, economic, political, and communication tools available to it. The more territory Moscow acquires through conquest, the less capable it is to care for territory already under its control as well as tend to Russia’s own needs. In particular, greater economic pressures will be placed on Russia’s already fragile economy. Despite his efforts to make things right in Russia, Putin must spend an inordinate amount of time mitigating existing hardships and the effects of malfunctions across the board in Russia’s government system and its society.

3. Chasing the Unattainable

Perhaps the type of success Putin really wants for Russia is unattainable, not by some fault of his own, but rather because its problems are too great, run too deep. He may have run out of answers to put Russia on real upward trajectory given the capabilities and possibilities of the country. Not being remiss, he has used all tools available to him, yet big improvements have not been seen. Putin’s pride may have been a bit marred by this reality. He, better than anyone, knows what Russia is and what it is not. For all that he has done, he has not led Russia, to use a phrase from John Le Carré, “out of the darkness into an age reason.” In a significant endeavor, there is always the potential to become lost. It would seem, consciously or unconsciously, Putin may simply be moving at a deliberate speed or even procrastinating a bit. When he cannot swim forward, he would prefer to tread water than sink. By continually displaying the strength, and the will, to keep his head above water in tough situations, Putin has become an inspiration to those around him. Most senior Russian officials are unwilling or are unable to take a complete look at the situation. Rather, they seem enamored with Putin, and would likely follow him no matter what. Knowing that has perhaps fed into his sense of accomplishment and confidence

Putin once said that the greatest danger to Russia comes from the West. He believes Western governments are driven to create disorder in Russia and seek to make it dependent of Western technologies. Theories propagated by Moscow that the struggle between East and West is ongoing have been energized by the whirlwind of anger and aggressive verbiage concerning the 2016 US Election meddling issue. The story of the meddling, confirmed and revealed by US intelligence community and political leaders on the national level, has been propelled by a strong, steady drum beat of reports in the US news media. Perhaps the election meddling, a black operation, should have been considered an unsurprising move by Putin. Perhaps due to his experience in the the intelligence industry, hseems to lead him to turn to comfortable tactics, technique, procedures, and methods from it when confronting his adversaries. The Kremlin vehemently denies any interference in the US elections. That may simply be protocal. Russian officials, such as Lavrov and Peskov, have gone as far as to say that insistence of various US sources that the meddling took place is a manifestation of some mild form of hysteria or paranoia. Yet, the Kremlin must be aware that such denials are implausible, and in fact, unreasonable. To respond in such a brazenly disingenuous manner in itself raises questions not just about the conduct Russia’s foreign and national security policy, but the true motives and intent behind Moscow’s moves. It appears that Putin’s personality and feelings influence policy as much as well-considered judgments.

Putin, better than anyone, knows what Russia is and what it is not. Perhaps the type of success Putin really wants for Russia is out of reach, unattainable, not by some fault of his own, but rather because it’s problems are too great, run too deep. He may have run out of answers to put Russia on a true upward trajectory. His pride may have been a bit marred by this reality. Despite his aptitude as a leader, he has failed to lead Russia, as a whole, “out of the darkness into an age reason.”

4. Tying-off the Election Meddling

Intelligence professionals might say that the correct and expected move in response to a covert operation that has failed very publicly, so miserably, would be to “tie it off”. Instead, as reported by US Intelligence agencies and the White House, Russia’s effort to meddle in the US elections has become recursive. This would mean that Putin, himself, wants it to continue. Although the meddling operation has been almost completely exposed, and one would expect that those responsible for it would feel some embarrassment over it, Moscow seems gratified about how that matter has served as a dazzling display of Russian boldness and capabilities. To that extent, the carnival-like approach of some US news media houses to the issue well-serves Moscow. Perhaps Putin has assessed that successive meddling efforts will last only for so long until US cyber countermeasures, awareness programs, retaliatory actions, and other steps eventually blunt their impact or render such efforts completely ineffective. Thus, he may feel that he has no need to stop the operation, as the US will most likely do it for him. Still, continued efforts to interfere in US elections may not end well. Russia must exit any roads that could lead to disaster.

Putin at 2018 campaign rally (above). Putin can be proud of his many accomplishments, of his rise to the most senior levels of power in Russia, eventually reaching the presidency, and of being able to make full use of his capabilities as Russia’s President. Yet, having an excessively high opinion of oneself or ones importance, is not conducive to authentic introspection for a busy leader. Putin’s unwillingness or inability to look deeply into himself has likely had some impact upon his decisions on matters such as Russia’s meddling in US elections.

Ego

The OED defines ego as a person’s sense of self-esteem or self-importance; in psychoanalysis, it is the part of the mind that mediates between the conscious and the unconscious mind, and is responsible for reality testing and a sense of personal identity. Ego, as first defined in the OED, can be useful in calibrated doses. A bit of an ego is needed in order for one to believe that new or far-reaching objectives can reached and tough, difficult things can be achieved. When it gets beyond that, problems tend to ensue. The ego is the voice inside an individual that really serves one purpose, and that is to make one feel better about whom one is, to lift oneself up. It will do whatever it needs to do to make that happen. The ego is also the voice inside of an individual that may drive one to kick another when he or she is down, causing them to feel bad about themselves. An example of Putin’s ego pushing beyond what some experts might call the normal parameters was the October 7, 2015 celebration of his 63rd birthday. Putin participated in a gala hockey game in Sochi, Russia, alongside former NHL stars and state officials. Putin’s team reportedly included several world-renowned players, such as Pavel Bure, formerly a member of the National Hockey League’s Vancouver Canucks. Putin’s team won the match 15-10. Putin scored 7 of his team’s 15 goals!

From a theological perspective, ego, much as pride, separates one from God. s the work of the devil, it is his tool that is used to separate us from God. The ego (Edging-God-Out) is considered the most powerful tool the devil has. It is deceiving in its ways, and makes one feel that one is serving others, when in reality one is serving oneself. Ego has no home is God’s creation. It is a distractive, impure thought, that leads to the destruction of self and others.

Putin can proud, in the ordinary sense, of his many accomplishments, of his rise to the most senior levels of power in Russia eventually reaching the presidency, and of being able to make full use of his capabilities as Russia’s President. With no intention of expressing sentimentality, it can be said that Putin went from a working class to middle class background in the Soviet Union to very top of Russia’s elite. As he recounts in First Person, and as his critics in the West remind without fail, Putin spent his spare time as a child hunting rats in the hallways of the apartment building where his family lived. To a degree, he was an upstart who alone, with the legacy of honorable and valorous service of his father and grandfather in the intelligence industry only available to inspire him, struggled to the highest level of the newly established Russian society. The arc of his story is that the professional and personal transformation of his life came with the fall of the Soviet Union. That event created the circumstances for his life to be that put him on the path to his true destiny. All of that being stated, humility would require that Putin recognize that his achievements are the result of God’s goodness and grace, not simply his own efforts. Ego would urge him not to think that way.

Perhaps Putin would be better able to understand the source of all good things in his life if he engaged in true introspection, a look within from the context of his faith. It appears that Putin’s unwillingness or inability to look deeply in himself has allowed him to develop an excessively high opinion of himself, a potent confidence that he alone is responsible for all positive outcomes. Holding a distorted sense of self-importance certainly would not facilitate introspection by a busy leader. His attitude of pride has also likely influenced his responses in contentious situations. All of this should not be used to conclude that Putin’s declarations about his faith have been counterfeit. Rather, there appears to be an imbalance between the influence of faith, particularly the restraining virtue of humility and the influence of a willful pride, an seemingly unruly desire for personal greatness. In time, a through his faith, he may find his value in God alone. God can work in mysterious ways.

Often, moves by Putin against the West resemble responses in a sport where there are challenges made and the challenger gains points when able to stand fast against his opponent’s counter moves and gains points based on the ability to knock the challenger back. In that vein, Russia’s move into Ukraine appeared to represent a dramatic victory. There was no military effort to push back against his move. There was no available capability among Western countries to defeat Russia’s challenge in Ukraine short of starting a war. Putin remains adamant about the correctness of that action. His position was amply expressed in his March 14, 2014 speech, declaring Russia’s annexation of Crimea. He noted that Russia’s economic collapse was worsened by destructive advice and false philanthropy of Western business and economic experts that did more to cripple his country. However, Putin’s moves in Ukraine likely brought him only limited satisfaction. He still has been unable to shape circumstances to his liking. He would particularly like to knock back moves by the West that he thinks were designed to demean Russia such as: the Magnitsky law, NATO Expansion (NATO Encroachment as dubbed by Moscow), the impact of years of uncongenial relations with Obama, and US and EU economic sanctions. His inability to change those things, and some others, has most likely left his ego a bit wounded.

An example of Putin’s ego pushing beyond what some experts might call the normal parameters was the October 7, 2015 celebration of his 63rd birthday. Putin participated in a gala hockey game in Sochi, Russia, alongside former NHL stars and state officials. Putin’s team reportedly included several world-renowned players. Putin’s team won the match 15-10. Putin scored 7 of his team’s 15 goals.

1. Magnitsky

In the West, particularly the US, there is a belief that in recent years, Putin has simply been reactive to the Magnitsky Act. It was not only a punitive measure aimed at Russia’s economy and business community, but struck at the heart of Putin’s ego. Through Magnitsky law, the West was interfering in Russia’s domestic affairs, good or bad, as if it were some second or third tier country, not as a global superpower with a nuclear arsenal. In retaliation, he would do the best he could to harm Western interests, even those of the US, not just over Magnitsky but a lot of other things. Counter sanctions would be the first step. Suffice it to say, election meddling took that retaliation to a new level. The Magnitsky Act, the official title of which is the Russia and Moldova Jackson-Vanik Repeal and Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, is named after Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian lawyer and auditor who in 2008 untangled a dense web of tax fraud and graft involving 23 companies and a total of $230 million linked to the Kremlin and individuals close to the government. Due to his efforts, Magnitsky became the target of investigations in Russia. When Magnitsky sued the Russian state for this alleged fraud, he was arrested at home in front of his kids, and kept in prison without charges, in filthy conditions, for nearly a year until he developed pancreatitis and gallstones. In November 2009, Magnitsky, at 37 years old, was found dead in his cell just days before his possible release. The Magnitsky Act was signed into law by Obama in December 2012 in response to the human rights abuses suffered by Magnitsky. The Magnitsky law at first blocked 18 Russian government officials and businessmen from entering the US froze any assets held by US banks, and banned their future use of US banking systems. The Act was expanded in 2016, and now sanctions apply to 44 suspected human rights abusers worldwide. William Browder, a US hedge fund manager, who at one time the largest foreign investor in Russia and hired Magnitsky for the corruption investigation that eventually led to his death, was a central figure in the bill’s passage. Two weeks after Obama signed the Magnitsky Act, Putin signed a bill that blocked adoption of Russian children by parents in the US. Russia then also imposed sanctions on Browder and found Magnitsky posthumously guilty of crimes. Supporters of the bill at the time cited mistreatment of Russian children by adoptive US parents as the reason for its passage. What made Russian officials so mad about the Magnitsky Act is that it was the first time that there was an obstacle to collecting profits from illegal activities home. Money acquired by rogue Russian officials through raids, extortion, forgery, and other illegal means was typically moved out of Russia were it was safe. Magnitsky froze those funds and made it difficult for them to enjoy their ill-gotten gains. The situation was made worse for some officials and businessmen close to Putin who had sanctions placed on them that froze their assets. All news media reports indicate that getting a handle on Magnitsky, killing it, has been an ongoing project of Russian Federation intelligence agencies.

2. NATO

Regarding NATO, in an interview published on January 11, 2016 in Bild, Putin essentially explained that he felt betrayed by the actions taken in Eastern Europe by the US, EU, and NATO at the end of the Cold War. Putin claimed that the former NATO Secretary General Manfred Worner had guaranteed NATO would not expand eastwards after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Putin perceives the US and EU as having acquitted themselves of ties to promises to avoid expanding further eastward, and arrogating for themselves the right to divine what would be in the best interest of all countries. He feels historians have ignored the machinations and struggles of people involved. Putn further stated in the Bild interview: “NATO and the USA wanted a complete victory over the Soviet Union. They wanted to sit on the throne in Europe alone. But they are sitting there, and we are talking about all these crises we would otherwise not have. You can also see this striving for an absolute triumph in the American missile defense plans.” Putin also quoted West German Parliamentarian Egon Bahr who stated in 1990: “If we do not now undertake clear steps to prevent a division of Europe, this will lead to Russia’s isolation.” Putin then quoted what he considered an edifying suggestion from Bahr on how to avert a future problem in Europe. According to Putin, Bahr proffered: “the USA, the then Soviet Union and the concerned states themselves should redefine a zone in Central Europe that would not be accessible to NATO with its military structure.” Putin’s view has not changed much since the interview. However, despite Putin’s certainty on this position, no former-Soviet republic wants to return to Russia or Moscow’s sphere of influence. Putin appears unwilling to accept today’s more complex reality. Pro-Russian movements and political circles in former Soviet republics do not represent the modern day trend.

Putin with binoculars at Zapad 2017 Military Exercises (above). Putin perceives the US and EU as having turned their backs on promises made to avoid expanding further eastward, and arrogating for themselves the right to divine what would be in the best interest of all countries. Despite Putin’s certainty of the West’s intrusive behavior, actually, no former-Soviet republic wants to return to Russia or Moscow’s sphere of influence. Putin appears unwilling to accept today’s more complex reality.

3. The EU

Putin has always viewed the EU as a project of deepening integration based on norms of business, law, and administration at variance from those emerging in Russia. Putin was also concerned that EU enlargement would become a means of excluding Russia from its “zones of traditional influence.” Even today, certain Russian actions indicate Moscow actively seeks to encourage members to withdraw from the EU sphere and discourage countries from joining it. Joint projects with European countries have allowed Russia to exploit their differences on political, economic and commercial issues creating a discordant harmony in the EU. A goal of such efforts has also been to undermine EU unity on sanctions. Even away from the former Soviet republics, Russia has engaged in efforts to undermine democratic processes in European countries. One method, confirmed by security experts, has been meddling in elections in a similar way to that widely reported to have occurred in the US.

4. Obama-Putin

Poor US-Russia relations were exacerbated by the uncongenial relationship between Putin and Obama. Indeed, Putin clashed repeatedly with the US President. Sensing a palpable weakness and timidity from Obama, Putin seemed to act more aggressively. The Russian military move that stood out was the capture of the Crimea and movement of troops into Eastern Ukraine to support pro-Russia separatists. There was nothing to encourage Putin to even try to negotiate beyond Magnitsky after Crimea. There was no room for him to turn back with ease or he would be unable to maintain his sense of dignity in doing so. Crimea would prove to be a useless chip to use in bartering a deal on Magnitsky. The US still views Magnitsky and Crimea as separate issues. Putin recognized from the attitudes and behavior of Obama administration officials that even the extreme measure of using subtle threats with nuclear weapons would not be emphatic enough to elicit a desired response from Washington because Obama administration officials would unlikely accept that such weapons could ever be used by Russia which was a projection of a view, a mental attitude, from their side. The Obama administration insisted that Putin negotiate them in the summer of 2013 and when he refused to do so, the administration cancelled a September 2013 summit meeting in Moscow between Putin and Obama. From that point forward, there was always “blood in water” that seemed to ignite Putin’s drive to make the Obama administration, and de facto the US, as uncomfortable and as unhappy as possible short of military confrontation.

5. US and EU Sanctions

As far as Putin sees it, painful sanctions from the US and EU, on top of the Magnitsky law, have damned relations between Russia and the West. Putin rejects the idea that the Trump administration is pushing for additional sanction against Russia and has explained new sanctions are the result of an ongoing domestic political struggle in the US. He has proffered that if it had not been Crimea or some other issue, they would still have come up with some other way to restrain Russia. Putin has admitted that the restrictions do not produce anything good, and he wants to work towards a global economy that functions without these restrictions. However, repetitive threats of further sanctions from the US and EU will place additional pressure on Putin’s ego and prompt him to consider means to shift the power equation. Feeling his back was against the wall, he has previously acted covertly to harm US and EU interests. A very apparent example of such action was his efforts to meddling in the 2016 US Presidential Election process. The US and EU must be ready to cope with a suite of actions he has planned and is prepared to use.

Convinced his behavior was an expression of ego, some Western experts believe that Putin may have succumbed to the vanity of his metaphoric crown. In effect, to them, Putin has been overwhelmed by his sense of the great power that he wields in Russia, and that he wants to convince other countries that he can wield power over them, too!

6. Succumbing to the Vanity of “His Crown”

Convinced his behavior is an expression of ego, some Western experts believe that Putin may have succumbed to the vanity of his metaphoric crown. To that extent, Putin has been overwhelmed by his sense for the great power that he wields in Russia, and wants to convince other countries that he can wield power over them, too! If Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk provinces were snatched from Kiev and fell firmly under the control of pro-Russian quasi-states of those entities and Russia, perhaps Putin would erect a statue of himself somewhere there or in Crimea much as one was erected of Zeus in Jerusalem by the Greek ruler of Syria, Antiochus IV. As for the people of those territories, and others in Transnistria, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, they may become the 21st century version of the malgré-nous, with many perhaps serving in the military against their will under the control of Russia. These scenarios are viewed by greatcharlie as long shots. It would surely raise Putin’s ire if he ever heard it. Although he is a dominant leader, he would likely prefer that his power was accepted, understood, and feared if need be, than depicted in such a monstrous or preposterous fashion. Yet, Putin may have behaved in a similar way recently when he announced an array of new “invincible” nuclear weapons.

On February 27, 2018 in a Moscow conference hall, with the back drop of a full-stage-sized screen protecting the Russian Federation flag, Putin gave one of his most bellicose, militaristic speeches since his March 14, 2014 regarding Crimea’s annexation. He told an audience of Russia’s elites that among weapons either in development or ready was a new intercontinental ballistic missile “with a practically unlimited range” able to attack via the North and South Poles and bypass any missile defense systems. Putin also spoke of a small nuclear-powered engine that could be fitted to what he said were low-flying, highly maneuverable cruise missiles, giving them a practically unlimited range. The new engine meant Russia was able to make a new type of weapon, nuclear missiles powered by nuclear rather than conventional fuel. Other new super weapons he listed included underwater nuclear drones, a supersonic weapon and a laser weapon. Putin backed his rhetoric by projecting video clips of what he said were some of the new missiles onto the giant screen behind him. Referring to the West, Putin stated, “They have not succeeded in holding Russia back,” which he said had ignored Moscow in the past, but would now have to sit up and listen. He further stated, “Now they need to take account of a new reality and understand that everything I have said today is not a bluff.”

Putin was speaking ahead of the March 18, 2018 Russian Federation Presidential Election. He has often used such harsh rhetoric to mobilize voter support and strengthen his narrative that Russia is under siege from the West. Yet, oddly enough, Putin emphasized that the new weapons systems could evade an Obama-era missile shield, which was designed to protect European allies from attacks by a specific rogue country in the Middle East and possibly terrorist groups, not Russia’s massive nuclear arsenal. He spoke about Moscow being ignored which was really a problem he had with the Obama administration. Indeed, most of what Putin said seemed to evince that lingering pains were still being felt from harsh exchanges with Obama. With Obama off the scene, and apparently developing military responses to cope with a follow on US presidency under former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Putin simply projected all of his anger toward Trump. Metaphorically, Putin seemed to “swinging after the bell.” So hurt was his ego that he has acted by building Russia’s nuclear arsenal up in a way the no US leader could ever deny the threat to US security that Russia poses. Being able to make that statement likely soothed his ego somewhat.

Religious scholars might state that Putin’s strong, perceptible ego contradicts his declaration of faith. The ego does not allow for the presence of God in ones life. Many have self-destructed as a result of their veneration of self. The ego needs to be overcome and removed from ones heart in order to allow God to fill that space.

In the form of Putin’s face can be found much that is telling about the Russian leader. As of late, its countenance has been far from serene and kindly. The countenance of ones face, smiling or frowning, can effortlessly communicate to others how one is feeling, thinking. Photos of Putin’s face more often reveal a deep, piercing, consuming stare, reflecting the strong, self-assured, authoritative, no nonsense personality, of a conscientious, assertive, and aggressive leader.

Putin’s Countenance

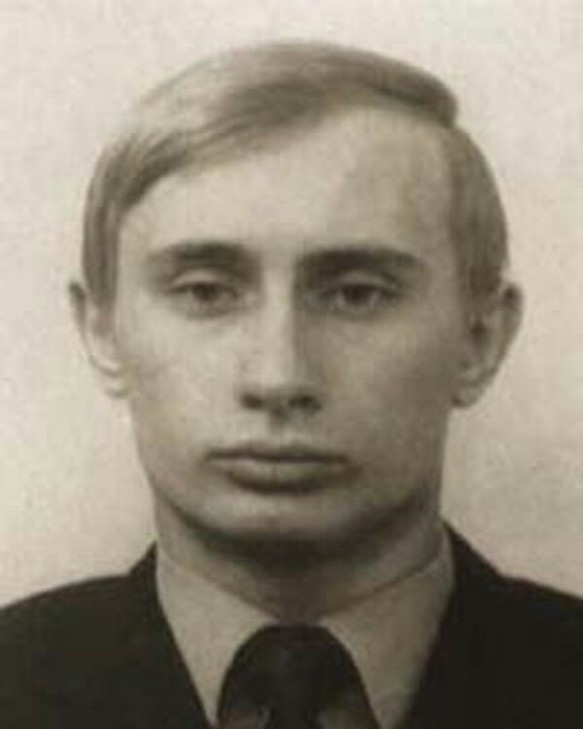

Imago animi vultus est, indices occuli. (The countenance is the portrait of the soul, and the eyes mark its intentions.) In the form of Putin face can be found much that is telling about the Russian leader. As of late, its countenance has been far from serene and kindly. The countenance of ones face, smiling or frowning, can effortlessly communicate to others how one is feeling, thinking. The face can also convey essential characteristics that make individuals who they are. In photos of President Putin in 2000, his eyes appear similar to those of the very best students of a fine university, watching and peering, learning and discerning constantly in order to best prepare himself to lead Russia into the future. It was before he had the eyes of an experienced, battle-scarred leader. Now, photos of Putin’s face more often reveal a deep, piercing, consuming stare, reflecting the strong, self-assured, authoritative, no nonsense personality, of a conscientious, assertive, and aggressive leader. Si fractus illabatur orbis, impavidum ferient ruinae. (If the world should break and fall on him, it would strike him fearless.)

1. The Conscientious Leader

The inner voice of individuals meeting with Putin may not sound an alarm immediately. After all, if Putin is anything, he is a conscientious leader and one would expect to see it reflected in Putin’s face. Conscientiousness is the personality trait of being careful, or vigilant. It implies a desire to do a task well, and to take obligations to others seriously. Conscientious people tend to be efficient and organized as opposed to easy-going and disorderly. They exhibit a tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement; they display planned rather than spontaneous behavior; and they are generally dependable. It is manifested in characteristic behaviors such as being neat and systematic; also including such elements as carefulness, thoroughness, and deliberation. The absence of apprehension, even anxiety, among some who meet with Putin is understandable, reasonable given that in social, as well as business situations, one can usually assume interlocutors mean what they say, are also personally invested in their interactions, and will display certain of manners, in some cases by protocol. Wanting to think well of others, wanting to connect with them, appearance, facial expressions, are looked upon benignly. Responding in this way is also a defense mechanism. Given his reputation, earned or not, aggression discerned in Putin’s face likely becomes sensate among his more worldly interlocutors. He might even be perceived through his countenance as being physically threatening without actually using any other part of his body to make gestures that could reasonably be identified as aggressive.

Somewhere in between, Putin can often appear to be what might be casually called “poker faced”, seemingly unresponsive to events swirling around him. During those moments, he is most likely evaluating everything and everyone, but keeping all his thinking and assessments locked inside himself. He may also be looking beyond the moment, considering what his next steps would be. Interlocutors will typically respond with faces of puzzlement and sometimes terror. Having the confidence to “face” foreign leaders in such a manner is a reflection of Putin’s assertiveness. (In the case of Trump, the response was likely disappointment, which masked a cauldron of intense rage. That should concern Putin and will become something to which he will need to find an answer.)

Putin gestures to a reporter at a press conference (above). Given his reputation, earned or not, aggression discerned in Putin’s face likely becomes sensate among his more worldly interlocutors. He might even be perceived as being physically threatening without actually making any aggressive gestures.

2. Putin’s “Assertiveness”

According to Fredric Neuman, Director of the Anxiety and Phobia Center at White Plains Hospital, being assertive means behaving in a way that is most likely to achieve one’s purpose. Under that definition, most successfully assertive individuals will have a suite of ways to act in given circumstances. Neuman explains that there are times when the right thing to do is to be conciliatory, and other times when resistance is appropriate. When one is actually attacked, verbally or otherwise, it may be appropriate to respond by resisting forcibly. Surely, there is a balance in Putin’s behavior in situations, but he has never been a wilting flower before anyone. A KGB colleague would say about Putin: “His hands did not tremble; he remained as cool as a mountain lake. He was no stranger to handling grave matters. He was expert at reading and manipulating people, and unfazed by violence.” Many foreign policy and human rights analysts in the West, and members of Russia’s opposition movement would say that Putin has amply demonstrated that he has no concern over sacrificing the well-being of Russians to further his geopolitical schemes and the avarice of colleagues. They report that he regularly persecutes those who protest. All of this runs contrary to image of Putin as a patriot. Those who study Putin would also point to the deaths of the statesman, politician, journalist, and opposition political leader, Boris Nemtsov; journalist Anna Politkovskaya; and, former KGB officer Alexander Litvinenko. Attention might also be directed to the deaths of 36 generals and admirals from 2001 to 2016. In the majority of cases, the causes of death listed were listed as suicides, heart attacks, or unknown. Among those who died are former Russian Federation National Security Adviser and Army Major General Vladimir Lebed and the Head of the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation Russian Federation Army Colonel-General Igor Sergun.

3. Putin the Predator

Certainly, Putin prepares for his meetings or any other official contacts in advance, by mining available information about his scheduled interlocutors and by considering all possible angles of how they might challenge him and how he would explain himself in a plausible, satisfying way. Such is the nature of politics as well as diplomacy. However, there are reportedly times when Putin, after considering information available, will simply declare his superior position relative to his interlocutor and let them know that they must accept what he says. His success in a meeting relies heavily upon how well he does his homework. Clearly, individuals as Putin can have a different context for learning about people. When Putin asks about an interlocutor’s family, home, office, even capabilities, it not small talk or the result of friendly interest. Rather, he may be signalling, warning, that he has already evaluated an interlocutor as a potential target. He may be confirming information or collecting more. He may also be testing ones vulnerability to falsehoods or how one might respond to unpleasant information. He is creating a perceptual framework for his interlocutor. Such tactics, techniques, procedures, and methods truly match those of a predator. “Human predators” often use deflection, social miscues, and misinformation to provide cover for themselves. They can use a contrived persona of charm and success to falsely engender trust. They have an exit plan in place, and are confident with regard to the outcome of their actions. Boiled down, they accomplish their deception using three steps: setting a goal; making a plan; and, compartmentalizing. By setting a goal, they know what they want and what it will take to get it or achieve it. They have no inhibitions about causing damage or harm. They stay focused. By making a plan, they not only determine ways to get what they want, but also develop exits if needed. By compartmentalizing, they detach themselves emotionally from attachments that might be embarrassed or be an annoyance if caught. They train themselves to give off no such tells, so they can pivot easily into a different persona. While some might acquire this skill as Putin through training and experience in the intelligence industry, others may simply lack any sense of remorse.

When immobilized or in a controlled “silence,” Putin’s face can also manifest a type of ambush predation in his thinking. He may be attempting to conceal his preparation to strike against a “troublesome or even threatening” party, if not at that moment, eventually. Ambush predators are carnivorous animals or other organisms, that capture or trap prey by stealth or by strategy, rather than by speed or by strength.

When immobilized or in a controlled “silence,” Putin’s face can also manifest a type of ambush predation in his thinking. He may be attempting to conceal his preparation to strike against a “troublesome or even threatening” party. Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals or other organisms, that capture or trap prey by stealth or by strategy, rather than by speed or by strength. In animals and humans, ambush predation is characterized by an animal scanning the environment from a concealed position and then rapidly executing a surprise attack. Animal ambush predators usually remain motionless, sometimes concealed, and wait for prey to come within ambush distance before pouncing. Ambush predators are often camouflaged, and may be solitary animals. This mode of predation may be less risky for the predator because lying-in-wait reduces exposure to its own predators. If the prey can move faster than the predator, it has a bit of an advantage over the ambush predator; however, if the active predator’s velocity increases, its advantage increases sharply.

There is a Christian religious allegory warning of the inner spiritual decay manifested by an outer physical decay presented in a historical framework that includes Leonardo da Vinci. As told, when Leonardo da Vinci was painting “The Last Supper”, he selected a young man, Pietri Bandinelli by name as the person to sit for the character of the Christ. Bandinelli was connected with the Milan Cathedral as chorister. Several years passed before Da Vinci’s masterpiece painting was complete. When he discovered that the character of Judas Iscariot was wanting, Da Vinci noticed a man in the streets of Rome who would serve as a perfect model. With shoulders far bent toward the ground, having an expression of cold, hardened, evil, saturnine, the man’s countenance was true to Da Vinci’s conception of Judas. In Da Vinci’s studio, the model began to look around, as if recalling incidents of years gone by. He then turned and with a look half-sad, yet one which told how hard it was to realize the change which had taken place, he stated, “Maestro, I was in this studio twenty-five years ago. I, then, sat for Christ.”

Perhaps Putin is simply making the most of what is. Putin may just be living life and doing the most he can for his country and the Russian people, no matter how limited. Satisfaction might come in the fact that he firmly believes things in Russia are better than they would be under the control of anyone else.

Other Shadows of Putin’s Interior

Nam libero tempore, cum soluta nobis est eligendi optio, cumque nihil impedit, quo minus id quo maxime placeat facere possimus, omnis voluptas assumenda est, omnis dolor repellendus. Temporibus autem quibusdam et aut officiis debitis aut rerum necessitatibus saepe eveniet, ut et voluptates repudiandae sint et molestiae non recusandae. Itaque earum rerum hic. Tenetur a sapiente delectus, ut aut reciendis voluptatibus maiores alias consequator aut preferendis dolorbus asperiores repellat. (In a free hour, when our power of choice is untrammelled and when nothing prevents our being able to do what we like best, every pleasure is to be welcomed and every pain avoided. But in certain circumstances and owing to the claims of duty or the obligations of business it will frequently occur that pleasures have to be repudiated and annoyances accepted. The wise man therefore always holds in these matters to this principle of selection: he rejects pleasures to secure other greater pleasures, or else he endures pains to avoid worse pains.) Although thngs may go wrong, Putin knows that disappointments in life are inevitable. Putin does not become discouraged or depressed nor does he withdraw from the action. Putin knows he must remain in control of himself as one of his duties as president, and as a duty to himself.

1. Risky Moves

As mentioned earlier, Putin may very well be simpy making the most of what is. Putin may just be living life and doing the most he can for his country and the Russian people, no matter how limited. Some satisfaction might come with the fact that he firmly believes things in Russia are better than they would be under the control of anyone else. Despite his optimism and confidence in his abilities, Putin must be careful of risky moves, creating new situations that may lead to discord, disharmony. For example, interfering in Ukraine was a move that felt he could keep a handle on. Regardless of how positive, professional, and genuine Trump administration efforts have been to build better relations between the US and Russia, it would seem Putin has decided that entering into a new relationship with US would have too many unknowns and possible pitfalls. Putin knows that the consequences of missteps can be severe. He has the memory of what former Russian President Boris Yeltsin experienced in the 1990s to guide him.

Although he holds power, Putin must always labor with the loneliness of leadership, the anxiety of decision making, and an awareness of threats to his well-being. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that there can be any real happiness for one who is under threat, in a country riddle with corrupt officials and a somewhat fragile system of law and order.

2. Dionysius and Damocles

Although he holds power, Putin must always labor with the loneliness of leadership, the anxiety of decision making, and an awareness of threats to his well-being. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that there can be any real happiness for one who is under constant threat, in a country riddle with corrupt officials and a somewhat fragile system of law and order. The ancient parable of Dionysius and Damocles, later known in Medieval literature, and the phrase “Sword of Damocles”, responds to this issue of leaders living under such apprehension. The parable was popularized by Cicero in his 45 B.C. book Tusculan Disputations. Cicero’s version of the tale centers on Dionysius II, a tyrannical king who once ruled over the Sicilian city of Syracuse during the 4th and 5th centuries B.C. Though wealthy and powerful, Dionysius was supremely unhappy. As a result of his iron-fisted rule, he had created many enemies. He was tormented by fears of assassination—so much so that he slept in a bedchamber surrounded by a moat and only trusted his daughters to shave his beard with a razor. Dionysius’ dissatisfaction came to a head one day after a court flatterer named Damocles showered him with compliments and remarked how blissful his life must be. “Since this life delights you,” an annoyed Dionysius replied, “do you wish to taste it yourself and make a trial of my good fortune?” When Damocles agreed, Dionysius seated him on a golden couch and ordered a host of servants wait on him. He was treated to succulent cuts of meat and lavished with scented perfumes and ointments. Damocles could not believe his luck, but just as he was starting to enjoy the life of a king, he noticed that Dionysius had also hung a razor-sharp sword from the ceiling. It was positioned over Damocles’ head, suspended only by a single strand of horsehair. From then on, the courtier’s fear for his life made it impossible for him to savor the opulence of the feast or enjoy the servants. After casting several nervous glances at the blade dangling above him, he asked to be excused, saying he no longer wished to be so fortunate.

Having so much hanging over his head, Putin has no time or desire to tolerate distractions. He does not suffer fools lightly. Putin’s ability to confound insincerity has been key to his ability to remain power. Early on as president, Putin effectively dealt with challenges posed by ultra-nationalists who were unable to temper their bigoted zeal, such as Vladimir Zhirinovsky of the extreme right Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, and Gennady Zyuganov of the Communist Party of Russia. The challenges posed by them lessened every year afterward. To the extent that such elements, and those far worse in Russia, could potentially react more aggressively to Putin’s efforts to maintain order, he most remain ever vigilant. Putin has also become skilled in implementing what critics have called “charm offensives,” explaining his ideas and actions in a manner that is easy, comfortable, assuring, and logical. Still, such moves are sometimes not enough. Indeed, during significant crises, it is very important for Putin to have advisers who fully understand his needs. For an overburdened, embattled leader, the encouragement of another, a paraclete, may often prove comforting.

Putin undoubtedly strives for a gesamtkunstwerk: a harmonious work environment. At the present, Putin is probably working with the best cabinet he has ever crafted both in terms of the quality of their work and chemistry. They may occasionally antagonize the overworked leader with a report not crafted to Putin’s liking, or worse, report on a setback. On such occasions, in contrast to his usual equanimity, Putin allegedly has become spectacularly incandescent.