A still image from the June 2023 video of Russian Air Force General Sergei Surovikin, commander of the Southern Group of the special military operation, in a relatively unkempt state–for the first time seen unshaven publicly and in an unpressed uniform sans insignia–implorng Wagner Group troops to halt their rebellion. As suggested in greatcharlie’s July 31, 2023 and August 1, 2023 posts, hypothetically attendant to the Wagner Group Rebellion, that according to the common wisdom, nearly sent the regime of Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin spiraling down the drain, may have been an effort to twinkle out dissenters and threats to the current Russian Federation government within the Russian Federation Armed Forces. It would be remiss for Putin’s most loyal subordinate, the Russian Federation security services, and possibly Putin himself, not to see the possibilities. The fact that several Russian Federation generals were detained by the security service in great part bears out greatcharlie’s supposition. If this was the case, it would also very likely have been the case that a decision to investigate military officers would have been impelled more by political dogma than authentic national security needs. Here, greatcharlie parses out the circumstances of the detention of several Russian Federation generals by the Russian Federation security services, with an emphasis on handling of Surovikin.

Except for some possible changes in the efficiencies in the Russian Federation Armed Forces’ prosecution of the Spetsial’noy Voyennoy Operatsii (Special Military Operation). So much outside of good reason appears to have guided top officials in the Ministerstva oborony Rossiyskoy Federatsii (Ministry of Defense Russian Federation hereinafter referred to as the Russian Federation Defense Ministry) and top commanders of the General’nyy shtab Vooruzhonnykh sil Rossiyskoy Federatsii (General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation hereinafter referred to as the Russian Federation General Staff), that hardly anything should be discounted as impossible at this point. For some in the West, that reality props open the door for potential moves that could be made by those same top commanders in the Russian Federation Armed Forces in the near future that would be positively unsettling to the government of Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin.

The private military organization, ChVK Vagnera, popularly known as Gruppa Vagnera (the Wagner Group) has fought alongside the Russian Federation Armed Forces since the first day of the invasion. The organization’s owner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, became greatly frustrated over the delinquencies, deficiencies, and ineptitude of the Russian Federation military leadership which his organization has been directed to work under. By 2023, Prigozhin unquestionably behaved as if he were frenzied, and perhaps justifiably and reasonably so, with the great injustice put upon Wagner Group troops in Ukraine as well as the troops of the Russian Federation Armed Forces. On June 23, 2023, however, Prigohzin shifted from simply accusing the Ministr Oborony Rossijskoj Federacii (Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation hereinafter referred to as the Russian Federation Defense Minister) Russian Army General Sergei Shoigu and Chief of the Russian Federation General Staff, Russian Army General Valery Gerasimov, of poorly conducting the then 16 month long special military operation when events took a graver turn. Prigozhin accused forces under the direction of Shoigu and Gerasimov of attacking Wagner Group camps in Ukraine with rockets, helicopter gunships and artillery and as he stated killing “a huge number of our comrades.” The Russian Federation Defense Ministry denied attacking the camps. In an act of daylight madness, Prigozhin then drove elements of the Wagner Group into the Russian Federation from Ukraine with the purpose of removing Shoigu and Gerasimov from their posts by force. His Wagner Group troops advanced to just 120 miles (200 kilometers) from Moscow. However a deal brokered by Belarus’ President Alexander Lukashenko was struck for the Wagner Group to halt. Prigozhin withdrew his forces to avoid “shedding Russian blood.”

As suggested in greatcharlie’s July 31, 2023 and August 1, 2023 posts mutually entitled, “The Wagner Group Rebellion: Insurrection or Staged Crisis? A Look Beyond the Common Wisdom (Parts 1 and 2)”, hypothetically attendant to the Wagner Group Rebellion may have been a hypothetical effort to twinkle out dissenters and threats to the current Russian Federation government within the Russian Federation Armed Forces. It would have been remiss for someone as the most loyal Putin subordinate, the Director of the Federal’naya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Federatsi (Russian Federation Federal Security Service) or FSB, Alexander Bortnikov, and possibly for Putin, not to see the possibilities. The FSB’s monitoring of responses to Prigohzin’s actions and possible communications with him should have been expected at least. The fact that several Russian Federation generals were detained by the security service in great part bears out greatcharlie’s supposition. If this was the case, it would also very likely be the case that a decision to investigate military officers would likely have been impelled more by political dogma than authentic national security needs. Indeed, in the Russian Federation security services, names have changed and so have technologies, but in the end that old chestnut from the Soviet days of “weeding out reactionaries and counterrevolutionaries” who supposedly pose a never-ending internal threat is apparently at the root and drives many of their activities. History has provided more than enough evidence of how well that turned out.

It is greatcharlie’s purpose here to parse out the circumstances of the detention of Surovikin and other Russian Federation generals by the Russian Federation security services to gain a better understanding of what is truly at the root of the action, what is likely occurring, and why the potential outcome for the Kremlin may very well be against its interests in more ways than one. Apparently suspected from the start of the whole Wagner Group episode was Commander in Chief of Vozdushno-kosmicheskiye sily (the Russian Aerospace Forces) or VKS General of the Army Sergei Surovikin, the deputy commander of the Joint Group of Forces in the Special Military Operation zone in Ukraine. Emphasis is placed on his detention and what surrounds it essentially as a yardstick to consider the plight of others. It is not concealed that greatcharlie believes the detention is a monumental injustice, a fantastic outrage. Human rights are available equitably to all humans, even Russian Federation generals. Hopefully, there will not be too much argument against that among a few readers. Some of what is discussed about the handling of Surovikin is written in the abstract but founded on long-reported treatment experienced by political activists, disfavored officials, and ordinary citizens alike whose interests “did not align with those of the government” and were thereby detained by the Russian Federation security services. It is greatcharlie’s contention that there is no reason to “search” for the truth. The true and pertinent is already known to all following the matter. No alternate facts to those generally reported in the Western newsmedia are revealed. No legal arguments based on Russian Federation law are offered here. Logic and reason are the tools brought to bear on the matter. Security service investigators surely have their “convictions”. Surovikin’s detention is hardly a subject that anyone could expect to discuss rationally with managers of the security services. Still, one might hope that at the top of the Russian Federation government, the light of good reason will eventually shine upon the matter. Quid leges sine moribus vanæ proficiunt? (what good are laws when there are no morals?)

On June 24, 2023, a video appeared on Telegram that depicted “talks” between Yevgeny Prigozhin, Russian Federation Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, and the Deputy Commander of the GRU, Vladimir Alekseyev, at the Southern Military District’s headquarters in Rostov-on-Don of which the Wagner Group had taken control. For the most part, Prigozhin’s noisome outbursts on his media channel on Telegram and in newsmedia interviews were made out of concern for the the outcome and outlook for the special military operation, the incompetence of the Russian Federation Defense Ministry and Russian Federation General Staff in prosecuting the war, and certainly the well-being of his troops. However, Prigozhin’s wailing was not solely been out of concern for his troops and troops in the Russian Federation Armed Forces. One might speculate that Prigozhin has been vocalizing a sense of disappointment felt among many other elites and members of Putin’s inner circle at how remarkably bad Shoigu and Gerasimov have served their President. It is also likely the case that Prigozhin’s shocking talk of a possible revolution expressed in early June 2023 were more than likely than not intended scare stories had the less noble aim of rattling the cages of many elites of the Russian Federation who did not favor him at all. However, an audience beyond the country’s borders starving for any information that would point to cracks in the wall of Putin’s regime. Those outbursts and, even more, the Wagner Group Rebellion, did much to provide such evidence.

Regarding Sedition and Insurrection in the Russian Federation

When asked during an interview broadcasted on CBS News “Face the Nation” in May 2023 what he thought was really behind the very public feud between Prigozhin and both Shoigu and Gerasimov, former Director of the US Central Intelligence Agency and US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates responded: “My view is, this is all taking place, with Putin’s approval.” Gates went on to explain the following: “This is- this is Putin, dividing and conquering. Putin, given how badly the war has gone, has to worry, at some point, that his military decides he’s a problem. By giving Prigozhin power and strengthening Prigozhin and letting him criticize the Ministry of Defense, Putin keeps them divided. If the two came together and decided Putin was a problem, then Putin would have a really big problem. So, my view is that- that Putin is sort of orchestrating this to a degree in the sense- or at least letting it go forward, because it serves his interest in keeping these two powerful forces at each other’s throats, rather than potentially beginning to collude against him.”

Imaginably, Gates, forever the consummate intelligence analyst, might appreciate fragments of an alternative perspective in the abstract on the perceptions of Prigozhin and his Wagner Group’s commanders and Russian Federation Armed Forces operations and senior operational commanders of the circumstances in Ukraine. For the most part, Prigozhin’s noisome outbursts on his media channel on Telegram and in newsmedia interviews were out of concern for the the outcome and outlook for the special military operation, the incompetence of the Russian Federation Defense Ministry and Russian Federation General Staff in prosecuting the war, and certainly the well-being of his troops. However, Prigozhin’s wailing was not solely out of his concern for his troops and troops in the Russian Federation Armed Forces. One might speculate that Prigozhin was vocalizing a sense of disappointment quietly and sometimes not so quietly felt among many other elites and members of Putin’s inner circle at how remarkably bad Shoigu and Gerasimov have served their President and their country. In effect, he may have taken on the job of being a figurative release valve for pent up steam building within many significant individuals in his country. It is also likely the case that Prigozhin’s shocking talk of a possible revolution expressed in early June 2023 were more than likely than not intended scare stories aimed at rattling the cages of many elites of the Russian Federation who did not favor him at all. However, Prigozhin’s decision to have a bit of fun at the expense of elite circles was very much ill-timed. An audience beyond the country’s borders starving for any information that would point to cracks in the wall of Putin’s regime.

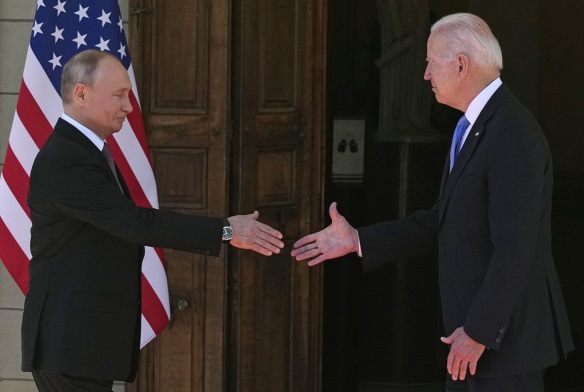

There is a perspective expressed in foreign and national security policy circles in the West that the time for Putin to leave power has come. Indeed, such is the intensity of negative feelings about Putin among many in West that the long-remembered words spoken by Oliver Cromwell in the House of Commons in 1653 concerning his ejection of the remaining members of the *Long Parliament” used famously on other occasions in the United Kingdom’s Parliament, well-expresses their sentiment: ‘You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!” Gates’ comments about the Russian Federation Armed Forces or the Wagner Group or both posing a threat to Putin’s power were nuanced and derive from a depth of understanding on the situation in the Russian Federation externally matched by few, it would fall in line not only with a multitude of mainstream analyses that have explored that possibility, and now feel their assessments were proven on-track with the advent of the Wagner Rebellion.

It is very important for those thinking along those lines to consider how the insurrection truly end. It did not end with the return of Wagner Group troops to their ans some leaving for Belarus with Prigozhin. That was one stage of the whole show. It ended when Prigozhin and 34 commanders of his Wagner Group, who only a week before were dubbed mutineers and treasonous by Putin in four very public addresses, met with the Russian Federation President in the Kremlin on June 29, 2023. The Kremlin confirmed the meeting occurred. According to the French newspaper Libération, Western intelligence services were aware of the momentous occasion, but they insist the meeting transpired on July 1, 2023. Two members of the Security Council of the Russian Federation attended the meeting: the director of Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki (Foreign Intelligence Service) or SVR, Sergei Naryshkin, and the director of Rosgvardiya (the National Guard of Russia) Viktor Zolotov. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told reporters: ““The commanders themselves outlined their version of events, emphasizing that they are soldiers and staunch supporters of the head of state and the supreme commander-in-chief.” Peskov continued: “They also said that they are ready to continue fighting for the motherland.”

With regard to prospective plotters among Russian Federation Armed Forces commanders, surely they understand that the special military operations’ present outcome was actually due to their failures and those of the Russian Federation General Staff and senior operational commanders. Surely, they were aware or should have been aware, just how deficient their forces truly were. This is hard saying for them, but the Russian Federation General Staff and senior operational commanders of the conventional forces were and still are inadequately suited to defend their country or to successfully invade a country such as Ukraine, especially when it is receiving robust support from NATO member countries and other countries with an interest in the matter. Due their own colossal failure to consider eventualities of such an enterprise, they did not foresee the deluge of Western military aid and training or what a huge impact it would have on the special military operations course. Strategic failures by Russian Federation General Staff and senior operational commanders and the inability to recognize opportunities for decisive action and turn failure into success continue to the point where its too painful for those concerned with the wastage of human lives to watch. Among the Ukrainian people, whose country the Russian Federation wrongfully and illegally invaded, maybe those failures might be viewed [as a relative blessing from on high. (Yet, what really can ever be called a blessing during a war: survival?)

If one might believe that what has transpired in Ukraine since February 2022 was all a deliberate act of subversion by the Russian Federation Defense Ministry and Russian Federation General Staff, the question would then be to what end: cui bono? The most likely immediate guess of those eager to see regime change of any kind in the Russian Federation might be that the plan was to set up Putin in order to foster his overthrow or elimination and their rise to power. Yet, both Shoigu and Gerasimov, given all of the supportive evidence publicly available on their respective atrocious management of two huge organizations, would have a better chance of achieving a decisive victory over Ukraine than controlling the Russian Federation with a modicum of competence. Unless megalomania and self-deception are controlling elements to an enormous extent in the respective thinking of both generals, they are surely aware that ruling the Russian people would be out of their sphere, beyond their faculties. Readers must pardon greatcharlie’s frankness, but given that Shoigu and Gerasimov are psychologically able to remain standing upright and stare calmly at a military disaster of such magnitude for their country’s armed forces, another possibility not to consider lightly is that either one or both may be psychologically unstable. This allegation shall be left for mental health professionals and behavioral scientists to parse out in the round.

Certainly, Putin had authority over what transpired but had no expert role in the technical management of any of it. Imaginably, top Russian Federation Armed Forces commanders could still hold Putin accountable for all that has occurred in Ukraine or dare to say such things in public or private, however they should guard against such delusional thinking even in their darkest moments. With the idea of overthrowing Putin being bandied about, doubtlessly, the security services have been very much on the prowl, more so now than ever, watching, listening, and hoping to pick up the trail on anything even slightly out of order.

Putin (left) and Director of the Federal’naya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Federatsi (Russian Federation Federal Security Service) or FSB, Alexander Bortnikov, talk along a corridor followed by stout securitymen. From a security service perspective universally, the handling of the Wagner Group Rebellion could be looked upon as an abysmal fiasco. The Russian Federation security services flubbed it. The Russian Federation security services stood seemingly immobilized, flat-footed on the ground, while thousands of ostensibly angry mercenaries drove toward Moscow. Amazingly, Putin has praised their rapid action on the matter more than once. In the aftermath, there was what greatcharlie characterizes as a frenzied rush by the security services to throw the blame on others for the singular happenings in late June 2023 which resulted in the detention and dismissal of several senior military officers. In that action, there has not been too much talk from the Kremlin. Yet, that aspect was somewhat foreshadowed by an a June 25, 2023 address given by Putin at the end of the Wagner Group Rebellion. That address created the prospect that a new wave of aggressive anti-subversion projects would be forthcoming as a consequence of the disturbance.

Background on the Russian Federation Security Services

During his July 27, 2023 address at the Kremilin’s Cathedral Square, Putin enumerated the organizations that fall under the heading, the security services of the Russian Federation He included the following: the Federal Security Service; National Guard; Interior Ministry; Federal Guard Service; and, the Defense Ministry.

Federal Security Service

Federal’naya sluzhba bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Federatsii (The Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation) or FSB, is the principal security service of the Russian Federation. The primary responsibilities are within the country and in certain circumstances,, externally,, are: counterintelligence, internal and border security, counterterrorism, surveillance and the investigation all other capitol crimes, violations of federal law violations, and unenumerated and unforeseen national security matters.

The National Guard

Federal’naya sluzhba voysk natsional’noy gvardii Rossiyskoy Federatsii (Federal Service of the Troops of the National Guard of the Russian Federation) or Rosgvardiya is the country’s internal military force, comprising an independent agency that reports directly to Putin under his powers as Supreme Commander-in-Chief and Chairman of the Security Council of the Russian Federation. The National Guard is not an element of the Russian Federation Armed Forces. In 2016, Putin signed a law establishing the federal executive bureaucracy. The stated mission of the National Guard is securing the Russian Federation’s borders, serving as the lead agency on gun control, combating terrorism and organized crime, protecting public order and guarding important federal properties.

Interior Ministry

Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del Rossiyskoy Federatsii (Ministry of Interior of the Russian Federation) or MVD is responsible for law enforcement within the country by performing tasks as described I n the names of its main agencies: the Police of Russia, Migration Affairs, Drugs Control, Traffic Safety, the Centre for Combating Extremism, and the Investigative Department.

Federal Guard Service

Federalnaya sluzhba okhrany (the Federal Guard Service of the Russian Federation) or FSO, is the federal government agency concerned with the tasks related to the protection of the most senior national officials as mandated by the relevant law, to include Putin. The FSO is also responsibile for the physical security of certain federal properties.

Defense Ministry

With regard to the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, it is not a security service per se, but technically plays an in security service role, being able to provide supporting ground, air, and navalnavalNaval assets when needed to support the main security organizations. Penultimately, the Defense Minister exercises day-to-day administrative and operational authority over the Russian Federation Armed Forces. The Russian Federation General Staff executes the Russian Federation President’s and the Russian Federation Defense Minister’s instructions and orders. Ultimately, the Russian Federation President is the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Federation Armed Forces and directs the activity of the Russian Federation Defense Ministry.

From a security service perspective universally, the handling of the Wagner Group Rebellion could be looked upon as an abysmal fiasco. The Russian Federation security services flubbed it. To all intents and purposes, the Russian Federation security services stood seemingly immobilized, flat-footed on the ground, while thousands of ostensibly angry mercenaries drove toward Moscow Amazingly, Putin has praised their rapid action on the matter more than once. (Perhaps that was an expression of his crni humor and it escaped the vast majority of listeners.) In the aftermath, there was what greatcharlie characterizes as a frenzied rush by the security services to throw the blame on others for the singular happenings in late June 2023 which resulted in the detention and dismissal of several senior military officers. In that action, there has not been too much talk from the Kremlin. Yet, that aspect was somewhat foreshadowed by a June 25, 2023 address given by Putin at the end of Wagner Group Rebellion. That address created the prospect that a new wave of aggressive anti-subversion projects would be forthcoming as a consequence of the “disturbance”.

As greatcharlie noted in its aforementioned August 1, 2023 post, in his June 25, 2023 address to the Russian Federation on the Wagner Group Rebellion, Putin let the Russian people know that in response to any challenges of any kind he would use his full powers and those powers had no limits. Putin stated: “As the President of Russia and Supreme Commander-in-Chief, and as a citizen of Russia, I will take every effort to defend the country and protect the constitutional order as well as the lives, security and freedom of our citizens.” Putin then fired something better than a warning shot that went beyond the events of June 2023 to those similar to “all sorts of political adventurers and foreign forces” as he described players in the 1917 Revolution, seeking to benefit politically, economically, or even militarily by tearing the Russian Federation apart. Political opponents, “dangerous elements”, and foreign visitors likely have more to fear now in the Russian Federation than ever before. To that extent, it would be expected for the security services to single out examples from the senior ranks of the Russian Federation Armed Forces to terrorize them into believing none would be safe from their watchful eyes and protective hands. If even the slightest scent of sedition or insurrection emanated from their direction, the security services would much like a tiger in the jungle at its prey.

As the Wagner Group Rebellion took shape, many officials and observers in the West proffered that Prigozhin and his troops would not have been able to take over military facilities in southern Russia so easily and mount his rapid march on Moscow without collusion with some members of the military’s elite. It is possible that such assessments and even the words of Gates spoken about a possible military insurrection drove top officials into such a frenzy that they became more determined to light on any officer over the slightest suspicion. It is fairly unlikely that the security services could say for certain that any military officers were absolutely involved in the Wagner Group Rebellion or any other apparent plots. Nevertheless, action was expected, and action was taken. The noble pagan of Ancient Rome, the renown statesman and scholar Marcus Tulius Cicero (106 BC to 43 BC), attributed to the Athenian statesman Solon (c. 630 BC to 560 BC), the quote: “Rempublicam duabus rebus contineri dixit, præmio et pœna.” (A state is regulated by two things, reward and punishment.)

As it was reported in the Moscow Times on July 13, 2023, the Russian Federation security services began their search for suspected reactionaries by detaining at least 13 senior military officers and suspended or fired 15 others. These actions were taken in relation to the Wagner Group Rebellion. Although many of the military officers investigated began their careers in loyal service to the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union, and had excellent records of service since, ties to the Wagner Group, no matter how attenuated, provided ample cause for singling them out. There was evidently no reason for any of the officers to believe they were guilty of anything. All were apparently devoid of any instant fear. Apparently, not one attempted to act first by using resources available to general officers to take refuge from the security services or evade investigators upon their arrival to detain them. For each, the discovery that they were subjects of an investigation by the security must have come to each as a bolt out of the blue. Among the generals detained were Russian Air Force Lieutenant General Andrei Yudin, Deputy Commander of the Southern Group Forces in the Special Military Operation zone, and, Russian Army Lieutenant General Vladimir Alekseyev, the Deputy Commander of Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye Generalnovo Shtaba (Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff-Military Intelligence) or the GRU. Both generals were suspended from duty after their release. In Act 2 Scene 1 of William Shakespeare’s tragedy, The Life and Death of Julius Caesar (1599), the character Brutus, considers, in a soliloquy, his reasons for assassinating Caesar on the Ides of March, states words surely pertinent to thinking of the security services regarding the subjects of their investigations ostensibly for treasonous acts though such behavior was unseen: “And therefore think him as a serpent’s egg / Which, hatch’d, would, as his kind, grow mischievous, / And kill him in the shell.” With its own hand, the Russian Federation government is gutting its own military of premium commanders. Que puis-je dire?

The Moscow Times was first to report that General Sergei Surovikin had been detained. Surovikin, the highest-ranking general among the many commanders held, was likely “target number 1” of the security services. Citing the Financial Times, Bloomberg, and Russia’s independent investigative outlet iStories published similar reports to the effect that Surovikin had either been detained or only questioned and then later released. Yet, according to the Moscow Times, sources of the Wall Street Journal revealed that Surovikin was undergoing “repeated interrogations” and was not being held at a detention center, where reportedly Russian prison monitors have been unable to locate the general. Surovikin’s whereabouts are still unknown now weeks after the Wagner Group Rebellion. Neither the Kremlin nor the Russian Federation Defense Ministry have revealed anything concerning Surovikin’s whereabouts or his well-being.

As it was reported in the Moscow Times on July 13, 2023, the Russian Federation security services began their search for suspected reactionaries by detaining at least 13 senior military officers and suspended or fired 15 others. These actions were taken in relation to Wagner Group Rebellion. Citing the Wall Street Journal, the Moscow Times stated “The detentions are about cleaning the ranks of those who are believed can’t be trusted anymore.” Indeed, although many of the military officers investigated began their careers in loyal service to the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union, and had excellent records of service since, ties to the Wagner Group, no matter how attenuated, provided ample cause for singling them out. Among the generals detained were Russian Air Force Lieutenant General Andrei Yudin, Deputy Commander of the Southern Group Forces in the Special Military Operation zone, and, Russian Army Lieutenant General Vladimir Alekseyev, the Deputy Commander of Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye Generalnovo Shtaba (Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff-Military Intelligence) or the GRU. Both generals were suspended from duty after their release.

Background on Surovikin

Holding the rank of General of the Army, Sergei Vladimirovich Surovikin has served as the overall commander of the Joint Group of Forces in the Special Military Operation zone in Ukraine from October 8, 2022 to January 11, 2023, during which time helped shore up defenses across the battle lines after Ukraine’s counteroffensive last year. He was replaced as the top commander in January 2023 by Gerasimov but retained influence in running war operations while in command of the Southern Group Forces in the Special Military Operation zone.

He has been awarded the Order of the Red Star, the Order of Military Merit and the Order of Courage three times. He was awarded the medal and title Hero of the Russian Federation and the Order of St. George. Surovikin had already reached what normally would have been the pinnacle of a Russian officer’s career when on November 22, 2017 he took command of Voyska Vozdushno-Kosmicheskoy Oborony, Rossijskoj Federacii (the Russian Federation Aerospace Defense Forces. It was still a relatively new organization, established in 2015 when the decision was made by the Russian Federation Defense Ministry to combine Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily Rossii, (the Russian Air Force), Voyska Vozdushno-Kosmicheskoy Oborony, (the Air and Missile Defense Forces), and Kosmicheskie Voyska Rossii, (the Russian Space Forces), under one command.

Surovikin was born in Novosibirsk in Siberia on October 11,1966. He is currently 56, married, and has two daughters. Reportedly, Surovikin stands about 5 feet 10 inches. While many sources state Surovikin is Orthodox Catholic, presumably meaning Russian Orthodox Catholic, unknown to greatcharlie is the degree to which he is observant. After graduating from the Omsk Higher Military School in 1987, Surovikin began his career serving as a lieutenant in the Voyská Spetsiálnogo Naznachéniya (Special Purpose Military Units) or spetsnaz. Spetsnaz units, a carry over from the days of the Soviet Union, have been trained, and tasked as special forces and fielded in wartime as part of the GRU. Not much has been offered at least in the mainstream or independent newsmedia on Surovikin’s work in spetsnaz. He reportedly served in spetsnaz during the last stages of the War in Afghanistan, but the specific unit he was assigned to has not been identified. As is the case with special forces in most countries, the primary missions of spetsnaz are power projection (direct action), intelligence (reconnaissance), foreign internal defense (military assistance), and counterinsurgency. Fighting in the Afghan War in the latter stages when the US was conducting its covert operation to support the Soviet’s main opponent, the Mujahideen at full-bore was most likely a very challenging experience for Surovikin.

Surovikin discussing the situation in Ukraine during his period of service as the overall commander of the Joint Group of Forces in the Special Military Operation zone. The Moscow Times was first to report that General Sergei Surovikin had been detained. Surovikin, the highest-ranking general among the many commanders held, was likely “target number 1” of the security services. Citing the Financial Times, Bloomberg, and Russia’s independent investigative outlet iStories published similar reports to the effect that , which said Surovikin had either been detained or only questioned and then later released. Yet, according to the Moscow Times, sources of the Wall Street Journal revealed that Surovikin was undergoing “repeated interrogations” and was not being held at a detention center, where reportedly Russian prison monitors have been unable to locate the general. Surovikin’s whereabouts are still unknown now weeks after the Wagner Group Rebellion. Neither the Kremlin nor the Russian Federation Defense Ministry have revealed anything concerning Surovikin’s whereabouts or his well-being.

By August 1991, Surovikin was a captain and commander of the 1st Rifle Battalion in the 2nd Guards Tamanskaya Motor Rifle Division. When the coup d’état attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev was launched in Moscow by the self-declared Gosudarstvennyj Komitét Po Chrezvycháynomu Polozhéniyu (State Committee on the State of Emergency) or GKChP., orders were sent down by the GKChP requiring Surovikin to send his mechanized unit into the tunnel on the Garden Ring. He drove his vehicles into the barricades of a group of anti-coup protesters. Shortly after that, Surovikin was promoted to the rank of major. In 1995, he graduated from the renowned Frunze Military Academy. Surovikin participated in the Tajikistani Civil War where he commanded a motor rifle battalion. He then became chief of staff of the 92nd Motor Rifle Regiment, chief of staff and commander of the 149th Guards Motor Rifle Regiment and chief of staff of the 201st Motor Rifle Division. Whether due to qualifications, prompted by politics, or whatever might possibly be a factor under the Russian Federation’s system of government, Surovikin’s superior decided to prepare him for flag rank. In 2002, he graduated from Voyennaya Akademiya General’nogo Shtaba Vooruzhennykh Sil Rossijskoj Federacii (the Military Academy of the General Staff of the RussianFederation). He became commander of the 34th Motor Rifle Division at Yekaterinburg.

In March 2017, Surovikin began his first of two tours in Syria. The first was supposed to last about three months. It was reportedly part of an effort by Moscow to provide first-hand combat experience to as many high-ranking officers as possible. However, on June 9, 2017, Surovikin was introduced to the newsmedia as the Commander of the Russian Federation Armed Forces deployed to Syria. The Russian Federation Defense Ministry repeatedly credited Surovikin with achieving critical gains in Syria, saying that Russian and Syrian forces “liberated over 98 percent” of the country under him. In the fight against the Islamic terrorist group, ISIS, Surovikin is credited for directing the Syrian Arab Army when it lifted the siege of Deir al-Zour and the attack that recaptured Palmyra for the second and last time. On December 28, 2017 he was made a Hero of the Russian Federation for his leadership of the Group of Forces in Syria.

The security services were surely ready and willing to grab those that both their sister national security bureaucracies and elites as Shoigu and Gerasimov could point a finger at. If some document had been created listing those officers that the Russian Federation Defense Ministry and Russian Federation General Staff had doubts about, Surovikin’s name would surely have been placed on the top of that list. For those who might have thoughts of seditious thoughts or considering insurrection, they would surely suggest that Surovikin be their role model: “Dein Vorbild!”

Surovikin (left) proudly receives Order of St. George, 3rd degree, from an apparently satisfied Putin (right). For quite some time, Putin appeared to appreciate Surovikin and must have acknowledged that he was a sort of diamond in the rough. In its October 30, 2022 post entitled, “Brief Meditations on the Selection of Surovikin as Russia’s Overall Commander in Ukraine, His Capabilities, and Possibilities for His Success”, greatcharlie explained that politics of the highest realms of the Russian Federation likely played a considerable role in the decision to appoint Surovikin commander of the joint group of troops in the area of the special military operation. it would seem on its face that Putin and the general should have a very harmonious relationship. Surovikin’s loyalty and reliability was apparent in his performance in Syria. Surovikin, obedient to the letter, followed through violently in Syria, getting the results that Putin demanded.

How Jealousy and Envy Likely Poisoned the Thinking of Shoigu and Gerasimov on Surovikin

US officials briefed on intelligence concerning Surovikin’s detention have said they do not know if his was actively involved in the Wagner Group plot to abduct Shoigu and Gerasimov. Searching for reasons behind Surovikin’s detention, the Western newsmedia as well as Russia scholars and policy analysts have repeatedly noted that when he was selected as the commander of Russian Aerospace Forces in 2022 and as the Russian Federation’s overall commander in Ukraine, none other than Prigozhin very publicly welcomed his appointment to those posts, calling him a “legendary figure” and “born to serve his motherland”. These quotes and other supportive ones, along with a number of well-publicized links between Surovikin and Prigozhin, have fuelled rumors in the West that Surovikin may have been “purged” or put under investigation for his ties to the Wagner Group Rebellion. Alleged strong ties with the Wagner Group, even if fuelled by rumor, would indeed be more than enough for security service investigators to sink their teeth into.

Still, despite any perceived ties between Surovikin and Prigozhin, it is more likely the case that he was a fitting target for the security services because he was, and presumably still is, disfavored by Shoigu and Gerasimov for, all of things, possessing a military acumen that surpassed theirs by leaps and bounds. No one could have been more aware of how inept Shoigu and Gerasimov were than Surovikin. No one did more to make the duo’s inadequacies readily apparent just by doing his job right. Rather treasure their subordinate as someone who gets things done in the midst of the Russian Federation’s conundrum in Ukraine, at the nub of their concern over him was very likely jealousy, envy, and insecurity. Shoigu and Gerasimov have respectively demonstrated themselves to be very flawed men in their thinking and actions. It is conceivable that they would go a bit further and prove themselves prone to punish subordinates because of their talents. Que l’enfer est faux avec vous?

When Surovikin was promoted to overall commander of the Joint Group of Forces in the Special Military Operation zone on October 8, 2022, he began to make moves that brought some positive results and good news for the Russian Federation Armed Forces. Surovikin surely understood that leveling everything and starting from scratch is certainly not the answer, although he may have wanted to do so in many areas. Despite shortcomings of his forces in the field and accepting the situation as it actually was, Surovikin sought to solidify the position of the Russian Federation Armed Forces in Ukraine. Fully in his element in ground warfare, he stepped up better organized localized attacks to have a cumulative effect and push back on advances by Zbrojni syly Ukrayiny (the Ukrainian Armed Forces) at that time. His defensive moves reportedly raised worries among US military officials and officials in the administration of US President Joe Biden that Russia Federation troops might be able to withstand renewed Ukrainian offensives.

Yet Surovikin’s efforts, which were bearing fruit, did not appear to be enough to impress or satisfy his military superiors. One might wonder whether Surovikin was intentionally given a fool’s errand when given overall command in Ukraine. One might speculate it was part of a pre-concerted effort conjured up by his superiors, hoping to brand him with a mark of dishonor for failing to complete a mission to correct a near Intractable situation before he had even journeyed out to perform it. Readers may recall that it was greatcharlie’s prediction in its October 30, 2023 post entitled, “Brief Meditations on the Selection of Surovikin as Russia’s Overall Commander in Ukraine, His Capabilities, and Possibilities for His Success”, that the situation for Surovikin might in the end parallel that of the singular circumstances surrounding the renowned author of The History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides, (c. 460 BC–400 BC). Thucydides once was an Athenian general who was subsequently sacked and exiled following his failure to defend the Greek city of Amphipolis in Thrace. (During his exile, he began compiling histories and accounts of the war from various participants on all sides.) According to Thucydides’ own account in Book 4, chapter 105, section 1 of The History of the Peloponnesian War, he was ordered to go to Amphipolis in 424 because he had “great influence with the inhabitants of the mainland.” However, the renowned Spartan general Brasidas, aware that Thucydides was on Thasos and had established considerable influence with the people of Amphipolis, and concerned over possible reinforcements arriving by sea, acted quickly to offer moderate terms to the Amphipolitans for their surrender, which they accepted. Consequently, when Thucydides arrived at Amphipolis, the city had already fallen under Spartan control. As Amphipolis was of considerable strategic importance to Athens, reports that it was firmly under Spartan control were received with great alarm. Thucydides became the target popular indignation among the Athenians. As was the usual decision in such circumstances, Thucydides was exiled for his failure to “save” Amphipolis.

It also could have been the case that Surovikin’s ability to establish order from chaos convinced others they could grab glory from his success and claim his successful actions as their own. Surovikin’s replacement as overall commander in Ukraine was none other than Gerasimov. When Gerasimov arrived to take command of the special military operation from him, Surovikin was not dismissed as was the case with Thucydides. He became one of three deputies subordinate to Gerasimov in the Special Military Operation zone, which meant Surovikin’s sound military thinking, good insights, and reliable intuition would be at his disposal. Further, by keeping Surovikin in the mix, any negative feelings Putin might have developed over a dismissal would be avoided. At that time, he still appreciated Surovikin, and would have unlikely tolerated his dismissal and would likely have responded negatively to efforts to dismiss him. However, if his superiors were truly “gunning for him”, as suggested by greatcharlie, their efforts would hardly end with his demotion. It seems they managed to set up a better aimed second shot at him during the Wagner Group Rebellion.

Surovikin with laser pointer (left) and Shoigu (right). Putin is hardly oblivious to the dearth of true military talent among commanders of the Russian Federation Armed Forces as well as among his closest military advisers. Interestingly, even while he supported Shoigu’s decision to subordinate all private military contractors, militias, and volunteers fighting alongside the Russian Federation Armed Forces in Ukraine, Putin, at the meeting in Ulyanovsk, implied that criticism of his country’s military had been for the most part correct. He stated:. “At the start of the special military operation, we quickly realized that the ‘carpet generals’ [ . . . ] are not effective, to put it mildly.” Putin continued: “People started to come out of the shadows who we hadn’t heard or seen before, and they turned out to be very effective and made themselves useful.”

Putin is hardly oblivious to the dearth of true military talent among commanders of the Russian Federation Armed Forces as well as among his closest military advisers. Interestingly, even while he supported Shoigu’s decision to subordinate all private military contractors, militias, and volunteers fighting alongside the Russian Federation Armed Forces in Ukraine, at the meeting with bloggers in Russian Federation on June 23, 2023, Putin implied that criticism of his country’s military had been for the most part correct. He stated:. “At the start of the special military operation, we quickly realized that the ‘carpet generals’ [ . . .] are not effective, to put it mildly.” Putin continued: “People started to come out of the shadows who we hadn’t heard or seen before, and they turned out to be very effective and made themselves useful.” For quite some time, Putin appeared to appreciate Surovikin and must have acknowledged that he was a sort of diamond in the rough. In its October 30, 2022 post, greatcharlie explained that politics of the highest realms of the Russian Federation likely played a considerable role in the decision to appoint Surovikin commander of the joint group of troops in the area of the special military operation. On the face of it, one might have imagined Putin and the general would have a very harmonious relationship, Both were devout servants of the Soviet Union and desired to preserve their erstwhile country. Surovikin’s loyalty and reliability became most apparent to Putin through his performance in Syria. Surovikin, obedient to the letter, followed through violently in Syria, getting the results that Putin demanded.

The thought could not have escaped Gerasimov that Putin might be looking at Surovikin as his possible replacement. To find support for that idea, he would only need to look at his latest work product, the condition of the Russian Federation Armed Forces in Ukraine and the less than capable force he had developed and maintained in the years before the invasion. Gerasimov could very likely have been accused criminally as having failed immensely in keeping the armed forces prepared for war.

A matter that might presumably have caused Putin to look at Surovikin with a jaundiced eye would be his trustworthiness, particularly with regard to his management of the Strategic Rocket Forces as the commander of the Russian Aerospace Forces. Putin needs to be certain whether the commander of the crown jewels of the Russian Federation’s defense would be ready to carry out his orders to use the country’s most powerful forces without question. Control over the actions of his commanders has likely become the most uneasy matter for Putin to cope with. Putin does not want to be placed in the situation he has faced for months with his commanders in the field in Ukraine who he surely feels have failed to perform in a satisfactory manner. The poisonous words of Putin’s most senior military advisers would have been able to do the most damage to Surovikin on this matter. It would be overly generous and perhaps unreasonable to think Shoigu and Gerasimov would refrain from attacking Surovikin from that angle if given the opportunity. Vana quoque ad veros accessit fama timores. (Idle rumors were also added to well-founded fears.)

Surovikin (left) and Gerasimov (right). It would seem on its face that Putin and the general should have a very harmonious relationship, hardly oil and water. Surovikin’s loyalty and reliability was apparent in his performance in Syria. Surovikin, obedient to the letter, followed through violently in Syria, getting the results that Putin demanded. The thought could not have escaped Gerasimov that Putin might be looking at Surovikin as his possible replacement. To find support for that idea, he would only need to look at his latest work product, the condition of the Russian Federation Armed Forces in Ukraine and the less than capable force he had developed and maintained in the years before the invasion. Gerasimov could very likely have been accused criminally as having failed immensely in keeping the armed forces prepared for war.

By countenancing the detention of Surovikin, Shoigu and Gerasimov would have essentially given their blessing to the actions of the security services. When the guilt of an individual is near assured by such authority, and results are expected at the top, the faculty of thought can often be suspended, even lost every step of the way. By observation–empirical data gleaned from years of newsmedia reporting–this appears true for almost every country, sorry to say. (If this faulty practice at all sound familiar to readers from security services of other countries, change your ways today! (More easily said than done one would suppose.)) Sufficit unum lumen in tenebris. (A single light suffices in the darkness.)

Surovikin appears to have found himself in a pickle with Putin similar to that of Ancient Roman military leader Belisarius (c. 500 AD to 565 AD) with Roman Emperor Justinian I (482 AD to 565 AD). Far more than simply a military commander, Belisarius was one of the greatest of Antiquity. He has been dubbed by historians as “the Last of the Romans.” He conquered the Vandal Kingdom of North Africa in 9 months, then turned to conquer much of Italy. He was victorious against the Vandals at Tricamarum and Ad Decimum. He recaptured the city of Rome for the Empire and held on to it under siege despite the fact that in both seizing the city and defending it, his force was outnumbered. Although subsequently defeated by the Persians at Callinicum, he won a great victory against their forces at Dara. Belisarius repulsed invasion attempts by the Huns at Melantias and by the Persians at Ariminum by causing them to lift the siege of the city. Skilled at using deception in warfare, he led the Persian commander to withdraw without a fight. However, having accomplished all of this and more, in 562 AD, toxic advisers, jealous and envious of Belisarius’ success and favor with Justinian, managed to convince the emperor that his loyal commander was conspiring to overthrow him. He was found guilty at trial, stripped of rank, publicly humiliated, and imprisoned. After reconsidering the matter, Justinian pardoned Belisarius and demanded his release. He restored him to favor at the imperial court. Belisarius died very shortly afterward.

It would seem the security services are very much troubling Surovikin with a lengthy examination. One might imagine if the security services had a clear cut case against the Surovikin, they would have readily thrown a light on all that is dark to everyone about the matter by making some complacent public statement in a very grand way. Certainly, that would happen, albeit only if Putin sanctioned it. Out of sheer curiosity, it would be interesting to hear what sort of ragbag of dissonant trifles the security services have in their possession about Surovikin. In the aggregate, their evidence would unlikely amount to anything managers in any legitimate law enforcement organization elsewhere would find satisfactory or acceptable. Conceivably, any evidence possessed by the security services could hardly be more than circumstantial and unlikely exact, but surely whatever it possesses would be near enough for the security services to believe their case is solid. Each bit of nothing in their minds would presumably rate higher meaning. To that extent, one might assess in the truest sense, the supposed crimes of the suspected officers were featureless ones. Nos hæc novimus esse nihil. (We know that these things are nothing (i.e., mere trifles.)

Snakes are able to unhinge their jaws, which allows them to swallow animals much larger than their heads. After they devour the animal, their jaw hinge goes back into place. Much as with snakes, right or wrong, security service officials, whether in the Russian Federation or governments of freedom loving democracies of the West, will figuratively unhinge their jaws to devour “larger prey” such as Surovikin or any subject of an investigation for whatever recherché rationale or due to an investigator’s some very apparent mental abnormality, highly valued by them. Often too easily given the authority by their superiors who are usually eager to receive results, investigating security service officials are usually reluctant to release the subjects of their investigations even if it requires busting budgets by increasing staff and hours on the beat and increasing the use of technical resources to include contractors to collect evidence that unlikely existed. Errant investigators will continue to clamp down on their victim even when it is clear there are no substantial leads, or trifles, to follow up on. Curiously, superiors in most security service do not appear to circulate in a way to observe such aggressive investigative practices or hear from subordinates whether anything inordinate is transpiring. Typically, managers in the security services have come up from the same system and are unwilling to push too hard on anything thoroughly. They know the deal! To be sure, the behavior of investigators in the security services can be unhinged not as much in a physical way as with the snake’s jaw, but psychologically. Once its victim is completely figuratively devoured, broken in a real sense, their jaws will return to their original position.

Gerasimov (above) moves through a well-protected bunker to the rear of the frontlines in Ukraine. A matter that might presumably cause Putin to look at Surovikin with a jaundiced eye would be his trustworthiness particularly with regard to his management of the Strategic Rocket Forces as the commander of the Russian Aerospace Forces. Putin wants to be certain whether the commander of the crown jewels of the Russian Federation’s defense would be ready to carry out his orders to use the country’s most powerful forces without question. Control over the actions of his commanders has likely become the most uneasy matter for Putin to cope with. Surely Putin does not want to be placed in the situation he has faced for months with his commanders in the field in Ukraine who he surely feels have failed to perform in a satisfactory manner. The poisonous words of Putin’s most senior military advisers would have been able to do the most damage to Surovikin on this matter. It would be overly generous and perhaps unreasonable to think Shoigu and Gerasimov would refrain from attacking Surovikin from that angle if given the opportunity.

Gerasimov (above) moves through a well-protected bunker to the rear of the frontlines in Ukraine. A matter that might presumably cause Putin to look at Surovikin with a jaundiced eye would be his trustworthiness particularly with regard to his management of the Strategic Rocket Forces as the commander of the Russian Aerospace Forces. Putin wants to be certain whether the commander of the crown jewels of the Russian Federation’s defense would be ready to carry out his orders to use the country’s most powerful forces without question. Control over the actions of his commanders has likely become the most uneasy matter for Putin to cope with. Surely Putin does not want to be placed in the situation he has faced for months with his commanders in the field in Ukraine who he surely feels have failed to perform in a satisfactory manner. The poisonous words of Putin’s most senior military advisers would have been able to do the most damage to Surovikin on this matter. It would be overly generous and perhaps unreasonable to think Shoigu and Gerasimov would refrain from attacking Surovikin from that angle if given the opportunity.

On Bullying Surovikin

Turning to the Bard again, in Act 3, scene 3 of Shakespeare’s play Othello, the Moor of Venice (1603), the consummate antagonist, the ensign Iago, acting full bore in a dastardly campaign to destroy the commander, Othello, psychologically, seeks to create doubt in his mind about his wife Desdemona’s fidelity and that she could possibly be in love with his captain, Cassio, his most loyal subordinate. In convincing Othello that it would be a tremendous blow to his reputation if word of what was in reality a nonexistent relationship between the two, became widely known, Iago states the famous passage: “Good name in man and woman, dear my lord, / Is the immediate jewel of their souls: / Who steals my purse steals trash; ’tis something, nothing; / ‘Twas mine, ’tis his, and has been slave to thousands: / But he that filches from me my good name / Robs me of that which not enriches him / And makes me poor indeed.” While likely embarrassed, disheartened and potentially humiliated initially by the public spectacle and dishonor of his detention, the brave soldier, a former spetsnaz officer, will not so easily be driven past hope and into despair despite the worst the security services might be able to dish out. True, the message Surovikin recorded urging the Wagner Group troops to halt their “mutiny” was likely made at the suggestion of the security service which likely had him in their possession at the time. Yet, the possibility is greater than not that Surovikin truly wanted the whole episode with the Wagner Group to end in order to prevent an atrocious “blue on blue” clash, save the lives of much needed troops, and avoid doing anything that would give the Russian Federation’s opponents an advantage. Surovikin likely saw it as one more chance to be a good commander and patriot despite his difficult situation. Doubtlessly in their interrogation of Surovikin, investigators are very likely repeatedly testing every link of their conceivably defective and possibly contaminated chain of evidence. However, no fabricated disclosures or incriminating false confession under duress should be hoped for from Surovikin. A likely denouement would be the general’s call to higher service unless he is released. The security services would of course assure all that Surovikin had met his fate by his own hand if he were to die in their custody. Hopefully, none of that will transpire.

For the security services, among a hypothetical list of causes for continuing their questioning Surovikin would perhaps be an insufficient response from his headquarters on whether there was “ample” reason to be concerned over the Wagner Group in his area or whether he prepared to respond to any provocation by Wagner Group units, Surovikin should bear no guilt for having any knowledge about the Wagner Group Rebellion. It is likely that most, if not all the causes listed, would appear nonsensical to reasonable individuals, and particularly legal scholars.. The build up of Wagner Group units on the border between Ukraine and the Russian Federation was an open secret, open to the whole wide world.

Perhaps every Western capital, as well as the capitals in other regions concerned about Ukraine, was aware of it. Western intelligence appears to have been more fully informed on the details of what was transpiring on the border than the Russian Federation Defense Ministry and the Russian Federation General Staff and the security services in the aggregate. It brings to mind how difficult it seemed for the Russian Federation Armed Forces and the security services to monitor Prigozhin’s movements between Belarus and the Russian Federation after the rebellion. Time and effort was spent raiding empty homes garnering little more than wigs and some old gag photos, gold bars and automatic weapons, all of which were returned to their owner. In the meantime, Western intelligence had been monitoring every move he made by satellite. One might hazard a guess that the US Intelligence Community knew details such as what he was typically having for breakfast and lunch and how much time he was spending watching television. The juxtaposition of the respective approaches to investigating the two subjects by the security services is almost comical.

Surely, the Russian Federation Armed Forces and the security services themselves had a more than adequate opportunity to monitor and disrupt any plan of the Wagner Group, to prevent if from assembling and rolling out against the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, and long before the “mutineers” left their line of departure and reached Rostov-on-Don. The reason why they failed to act, robustly or discreetly, is anyone’s guess. The failure of the Russian Federation Armed Forces and security services to interfere with the Wagner Group before the situation took a grave turn was surely a worse act of enabling the rebellion than any other. If Surovikin is being held over any knowledge potentially possessed and withheld by him, he could hardly have concealed anything that everyone did not already know on the matter. As the whole saw how the whole episode played out, one might wonder what sort of special piece of information he could have held back. Recalling the dialogue from the 1979 blockbuster film “Apocalypse Now!”, a portion of a line spoken by the character US Army Captain Benjamin L. Willard is apropos in this case. With that line added on here, one could then state with considerable accuracy that charging anyone with having foreknowledge of the Wagner Group Rebellion would be “like handing out speeding tickets at the Indy 500.”

If Surovikin is being held over some possible errant words spoken by him, then, as suggested earlier, the time has long passed since the security services should have let Putin, the Russian people, and the world know they have got it out. However, such is surely not the case. Everything made publicly known so far points to the likelihood that they have no real case against Surovikin. Perchance the best case for which the security services are actually providing strong evidence is the case proving what an absolute abomination the Russian Federation government is. Some might argue that too is an “open secret”.

Regarding the inadequacies of the Russian Federation Armed Forces and the security services, greatcharlie need not go as far as to call attention to just how wrong their respective pre-invasion conclusions were about the Ukrainian people welcoming invading Russian Federation troops with open arms. One might infer from the quality of their previous work product, in the minds of security service investigators, no matter how implausible or off-kilter their cause for holding Surovikin might be, they believe there is good reason to detain Surovikin. They can “rest assured” that they have got the right man. Again, they have got it out! Complètement folle!

Interestingly, while Russia scholars and policy analysts will never recognize the sovereign territory of Ukraine in the Donbass as Novorossiya, it is supposedly a reality for the Russian Federation government. That being the case, if the Wagner Group on territory that was in the minds of Russian Federation officials now their country’s sovereign territory, whatever the Wagner Group was doing was a matter that fell primarily if not solely within the security services’ province. How inelegant it is for the security services to foist their responsibilities upon commanders of the Russian Federation Armed Forces on the battlefield who at that moment were swamped, struggling to prevent the Ukrainian Armed Forces from delivering a crushing military blow, sending the entire enterprise in Ukraine from swiftly spiraling downward into a defeat on a scale not seen since World War II. (Undoubtedly, with regard later offensives that have lead to grand defeats, some might call attention to the May 4, 1975 spring offensive (Chiến dịch mùa Xuân 1975), officially known as the General Offensive and Uprising of Spring 1975 (Tổng tiến công và nổi dậy mùa Xuân 1975), which was the final North Vietnamese campaign of the Vietnam War that led to the capture of Saigon on April 30, 1975, and the surrender and dissolution of Republic of Vietnam. Others might call attention to the May 2021 offensive of the wretched Taliban in blatant violation of a peace agreement that led to the capture of Kabul, the complete collapse of the internationally backed government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and subsequent dissolution of the robustly supported the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces on August 15 2021.)

Putin (center top) meeting with select members of the Russian Federation Defense Ministry, Russian Federation security services, and the Security Council during the Wagner Group Rebellion. For the security services, among a hypothetical list of causes for continuing their questioning Surovikin would perhaps be an insufficient response from his headquarters on whether there was “ample” reason to be concerned over the Wagner Group in his area or whether he prepared to respond to any provocation by Wagner Group units, Surovikin should bear no guilt for having any knowledge about the Wagner Group Rebellion. It is likely that most, if not all the causes listed, would appear nonsensical to reasonable individuals, and particularly legal scholars. The build up of Wagner Group units on the border between Ukraine and the Russian Federation was an open secret, open to the whole wide world.

Pitfalls for Military Officers Who Get Too Close to Political Matters

With Prigozhin being a very close associate of the Russian Federation President and, by reports, ostensibly under the control of the GRU and the Russian Federation General Staff, it is not too difficult to imagine Surovikin was most likely reluctant, or strongly desired, to stay out of matters closely concerning Prigozhin’s activities outside of military matters. By doing so, one could only bring unneeded trouble upon oneself. It would be impossible, without all of the facts of what was really the case, what was in play. One of the other aforementioned commanders detained and questioned by the security services, Alekseyev, the first deputy chief of the GRU, military intelligence, certainly would have known prying into whatever the Wagner Group was doing off the battlefield would be counterintuitive. He too would know just getting too close could result in trouble as the situations for Yudin, Alekseyev, and Surovikin clearly demonstrate.

In greatcharlie’s June 5, 2023 post entitled, “Commentary: Will the Ukraine War’s Course Stir Putin to Alter His Thinking and Seek Novel Ways Either to Win or to Reach a Peace Deal?”, a true picture of the thinking among the Russian people concerning service to the state–to the best understanding of greatcharlie–was outlined with frankness. At a time of national emergency, which the Ukraine War represents for the Russian Federation, some citizens may likely feel compelled to step forward to support their homeland. Since work as a foreign and national security policy analyst of a kind ostensibly would not include being shot at, it would seem safe enough for some to volunteer to serve. Yet, with all of that being stated, one must remain conscious of the fact that in the Russian Federation, individuals can face very difficult circumstances even following what could reasonably be called the innocuous contact with the federal government. This reality is at great variance with the general experience of individuals living in Western democracies after contact with respective governments. Of course, in some cases, Western governments, too, can find limitless ways to betray the expectations, faith, and trust of their citizens. (On this point, greatcharlie writes from experience.) For certain, laws concerning the people’s well-being can be legislated with some regularity in most countries but justice is very often harder to achieve.

To that extent, greatcharlie supposed that scholars and analysts outside of the foreign and national security policy bureaucracies would unlikely be quick to assist the Russian Federation government by providing any reports or interviews. There might be a morbid fear among many scholars and analysts outside of those organizations to offer insights and options in such a hypothetical situation believing it is possible that the failure to bring forth favorable outcomes, even if their concepts were obviously misunderstood or misapplied might only antagonize those who they earnestly sought to assist. Indeed, there perhaps would be reason to fear they would be held accountable for the result and some severe punishment would be leveled against them. Punishment might especially be a concern if Putin himself were to take direct interest in their efforts. If he were somehow personally disappointed by how information received negatively depicted or impacted an outcome, there would be good reason for those who supplied that information to worry. Many outside of the foreign and national security policy bureaucracies might feel that the whole issue of Ukraine is such an emotionally charged issue among Putin and his advisers that, perchance, nothing offered would likely be deemed satisfactory. It would be enough of a tragedy to simply find themselves and those close to them under the radar of hostile individuals with whom anyone living in relative peace would loathe to be in contact. Given all the imaginable pitfalls, based stories of the experiences of others, those among the Russian people who might have something of real value to contribute may decide, or their respective families and friends might advise, that it would be far better and safer not to get involved.

Putin (left) and Shoigu (right). Behind Putin to the left is Alexei Dyumin, Acting Governor of the Tula Region of the Russian Federation. Behind the pensive Shoigu, to the left, is Russian Federation Deputy Defense Minister and State Secretary, General of the Reserve Army, Nikolai Pankov. Dyumin holds the rank of lieutenant general in the Russian Army. He once served as the chief security guard and assistant of Russian Federation President before Putin promoted him to lead the Russian Federation’s Special Operations Forces which he oversaw during the annexation of Crimea in 2014. The following year, he became Deputy Defense Minister. He was awarded the title of Hero of the Russian Federation. It has been suggested within the Western newsmedia that Dyumin would likely replace Shoigu as Russian Federation Defense Minister if the need arose. Politics at the highest realms of the Russian Federation are complicated and dangerous. Those who really do not have “hold any cards” or are not “covered” politically much as Icarus of Ancient Greek mythology tend to get burned and fall whenever they intentionally or incidentally get too close to the fire.

Beyond being shocked and surprised, Surovikin was likely horrified upon initially discovering that the entire political cabaret of the Wagner Group Rebellion was being launched in the eastern sector of his area of responsibility. If he had not been, he might have supposed the security services, to include the Border Guard and the National Guard, would be in the best position to put the brakes on the matter. He then might have expected the FSB would have the situation “well in hand”, going about interviewing Wagner Group commanders and detaining them if necessary. None of that happened. It turned out none of the security services took on the task of dealing with the Wagner Group. (Still, one might suggest in their own way, FSB managers did have the matter covered alright. They would select suspected, not necessarily guilty, co-conspirators after the fact, and deflect any culpability for their own failures.) One could imagine Surovikin’s facial expression upon hearing from security service investigators. Perhaps he was stoic.

Focused on his main task, fighting the illegal war Putin started, Surovikin was unlikely putting too much time into the political theater that transpired nearby. In less distracting circumstance, experience in the service of the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation would likely have caused Surovikin to brace himself for the worst possibility of being suspected of collusion speciously based upon the geographical relation of his command and the assembly area of the Wagner Group for its rebellion as well as for “allowing” the insurrection to transpire in the area under his command. In the armed forces of a normal country, there would scarcely be an expectation for Surovikin to lend concern to whatever the Wagner Group was doing. There would really be no professional side to doing so. Again, at the time when everything took flight, he was doing his real job, fighting an illegal war initiated by the Kremlin. The security services, however, are unable to see that. They exist in an alternate reality–a cognitive bubble–much as they do in every country. That is something that legislatures and executive authorities in democracies must do far more to guard against.

The mainstream opinion reported in the West generally is that Surovikin is a skilled commander who would likely continue to pose problems for the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The New York Times described Surovikin as a respected military leader who helped shore up defenses across the battle lines after Ukraine’s counteroffensive last year, analysts say. He was replaced as the top commander in January but retained influence in running war operations and remains popular among the troops. Perhaps he is looked upon as something far less formidable by the Russian Federation Defense Ministry and Russian Federation General Staff on which he served. A common theme heard during the Wagner Group Rebellion was that the action was benefitting the enemies of the Russian Federation. Among the points made in his July 24, 2023 “Address to the Nation” concerning the Wagner Group Rebellion, Putin explained that external threats–tacitly understood to be the US and other Western countries–would exploit anything that might provide advantage for them against the Russian Federation. Putin stated: “Today, Russia is waging a tough struggle for its future, repelling the aggression of neo-Nazis and their patrons. The entire military, economic and informational machine of the West is directed against us. We are fighting for the lives and security of our people, for our sovereignty and independence, for the right to be and remain Russia, a state with a thousand-year history. Putin continued: “This battle, when the fate of our nation is being decided, requires consolidation of all forces. It requires unity, consolidation and a sense of responsibility, and everything that weakens us, any strife that our external enemies can use and do so to subvert us from within, must be discarded.” Oddly enough, in a dark, cynical twist, Surovikin, in a relatively unkempt state–for the first time seen unshaven publicly and in an unpressed uniform sans insignia–and propping himself in a chair against a wall in an unmilitary fashion, spoke briefly on a video recording. Surovikin remarked: “We fought together with you, took risks, we won together,” He then entreated: “We are of the same blood, we are warriors. I urge you to stop.” Surovikin added: “The enemy is just waiting for our internal political situation to deteriorate.” He then implored the Wagner Group troops: “Before it is too late . . . you must submit to the will and order of the people’s president of the Russian Federation. Stop the columns and return them to their permanent bases.” It is almost certain that when the video was produced, Surovikin was already being held–and likely being roughly handled–by security service investigators.

Readers may compare Surovikin’s typically appearance depicted in this photo (above) with his deportment in the June 24, 2023 video and judge for themselves the general is doing well. In the video broadcasted on June 24, 2023, Surovikin as aforementioned, appears in an unkempt state, unshaven and wearing an unpressed uniform. Focused on his main task, fighting the illegal war Putin started, Surovikin was unlikely to put too much time into the political theater that transpired nearby. In less distracting circumstance, experience in the service of the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation would likely have caused Surovikin to brace himself for the worst possibility of being suspected of collusion speciously based upon the geographical relation of his command and the assembly area of the Wagner Group for its rebellion as well as for “allowing” the insurrection to transpire in the area under his command. In the armed forces of a normal country, there would scarcely be an expectation for Surovikin to lend concern to whatever the Wagner Group was doing. There would really be no professional side to doing so. Again, at the time when everything took flight, he was doing his job.

With regard to what the Moscow’s perceived enemies were actually thinking and saying about the Wagner Group Rebellion, the New York Times on June 27, 2023 reported that US officials interviewed, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence, explained concerning Surovikin and the Wagner Group Rebellion that they have avoided discussing what they and their allies know publicly to avoid feeding Putin’s narrative that the unrest was orchestrated by the West.